How do you identify a bird that you’ve seen?

How do you report your sighting? And most importantly, how do you get it out of your attic safely?

In the middle of the night, I heard Jordan calling my name to meet him upstairs. It was 2 a.m. and my guess was that he had found a live animal — great. We live in a 1901 townhouse in downtown Frankfort, and since the upstairs is currently under renovation, we have been living out of the basement and the first floor exclusively since the snow fell. Who knows how long whatever it was had been nesting up there.

Disoriented by the cold and the light, it took me a few minutes to realize what Jordan had seen. He was pointing his flashlight directly into the bright yellow eyes of a very small owl, probably no taller than the length of my hand, that was perched atop a mattress that was tilted on its side and stacked in the hallway. Was it a baby? We had no idea. How had it gotten in here? We had no idea. How would we get it out? We had no idea.

The first step was to quarantine the area from the dog and cat, who were both very curious as to what could possibly be going on in the middle of the night in the unused part of the house. Next, we decided to open up as many windows as possible, to try to flush the bird out without having to get super close to it. There was one window at the end of the hallway, but we couldn’t get to that with the owl in the way. There was another window at the opposite end of the hallway, so Jordan opened that and removed the screen. There are two bedrooms perpendicular to the hallway, and I closed the door of one bedroom and opened the window of the other. When Jordan got close, the owl, of course, flew to the one hallway window that we had not been able to open. Great, now what? (Luckily, it had not run into the glass, as I had feared, since we had been effectively blinding it. Instead, it just landed on the window sill and sat there.)

Jordan had me go into the open-window bedroom and hide behind the door; in case the owl decided to fly in my direction, he didn’t want me to be in the way. He then grabbed a towel and walked slowly toward the owl, which had perched on the sill of the closed hallway window. I couldn’t see what happened next, since I was hiding behind the door, but then he came in carefully holding the owl in a towel. He walked over to the window, slowly peeled back the towel, and cautiously lifted his hand toward the window. Still, the bird just laid there. I wondered if he had injured himself, having been flying around, bumping into things, and making the noises that had awoken us. But Jordan then put his hand actually out the window, and the owl took off, its large wingspan surprising me for such a small bird.

As we closed the windows, walked back downstairs to the wondering eyes of the dog and cat, and dove under the blankets, I remarked how I wished that we had thought to take a photo or a video.

Identifying Your Bird

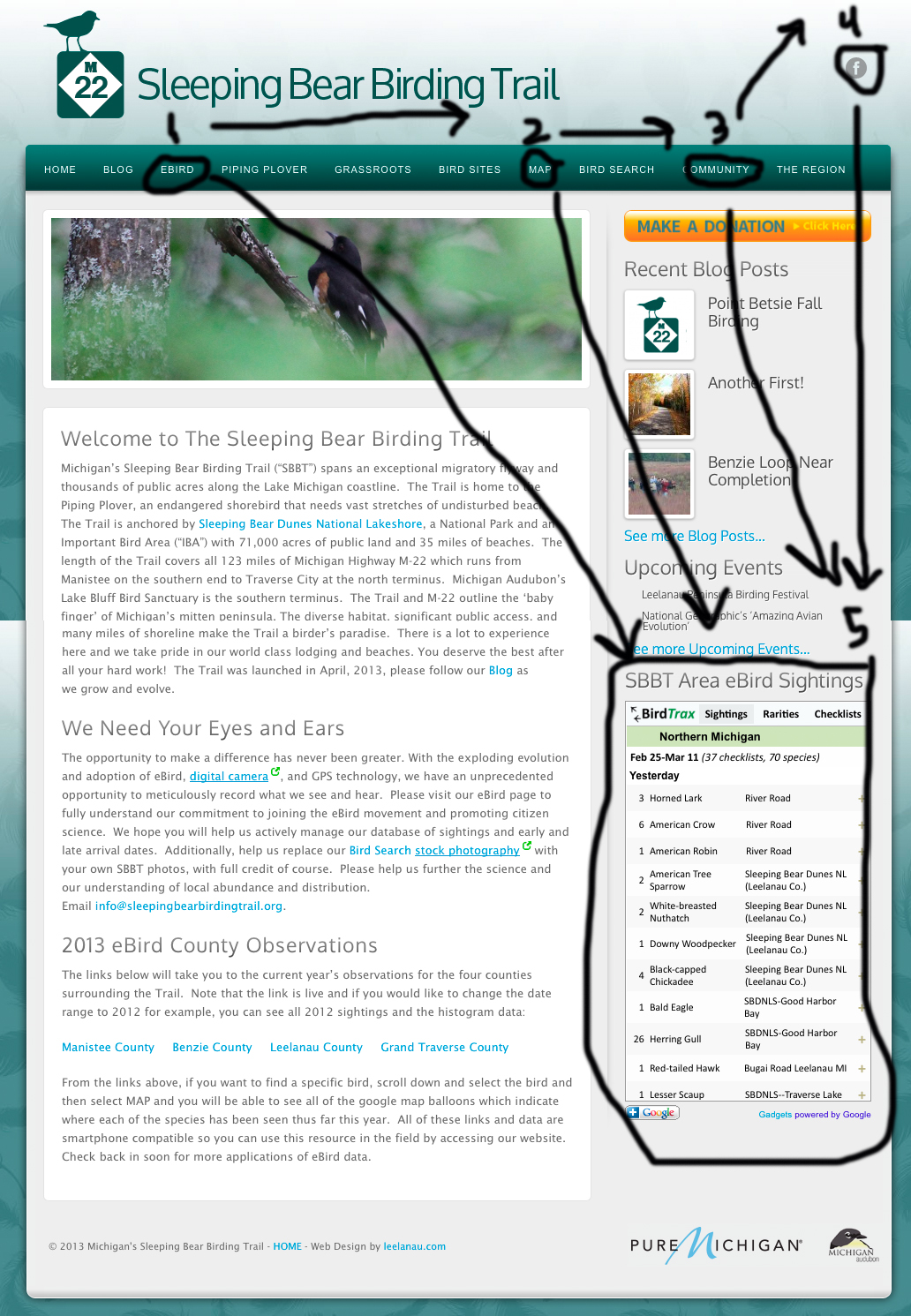

But the real questions started at daybreak, once we both had our wits about us again — what kind of owl had it been? Fortunately, Jordan recently built a website called SleepingBearBirdingTrail.org, a comprehensive one-stop shop for any bird that you might see within the Northern Michigan region. The search tool is great — we only had to type in “owl” in this case, but if you don’t know what kind of bird you’ve seen, leave the “Search Bird Name” entry blank and leave the default setting of “Search Bird Types” as “All Types”, then click the “Search” button, and all 321 species that have been sighted within the Sleeping Bear Dunes Trail will pop up, with photos and descriptions of each.

In our case, our little friend was an Aegolius acadicus, or Northern Saw-Whet Owl, which the sites describes as:

“Rare year-round resident. Confirmed breeder. This woodland cavity nester is Michigan’s smallest owl species. Due to its small size and secretive habits, Saw-whets are very difficult to find. One individual was seen February through March at Pyramid Point and other records are scattered throughout the year. An active nest was found near Empire in the early 1970s.”

At this, we got really excited. “We should report this, if they’re rare!” I said. Jordan agreed. But how does one do this? Good question, that neither of us knew the answer to before this morning.

Reporting Your Bird

At first, I clicked on the eBird link in the navigation bar on top of the SleepingBearBirdingTrail.org site. But this felt like falling into a rabbit hole, in my opinion. There was lots of text about widgets and the Audubon Society but nothing that helped me to report my sighting. Next, I clicked on Map in the navigation bar, hoping that would show a map of where other people had seen various birds, but no luck there. Instead, there is a Google Map of places to go birding. (I guess that makes sense.) Then I tried clicking on Community, hoping that there would be a link to a tool to report my bird, but no such luck, as it was just a bunch of links to various other birding organizations in the region.

Since there was no “About Us” or “Contact Us” anywhere that I could find, I was beginning to feel like I wasn’t going to be able to report my sighting of this rare owl. But then I saw the Facebook icon at the very top of the page, and I clicked on that — if nothing else, I was going to let them know via a quick post on their wall, and hope that someone would see it and enter it into some database for me. Feeling ready to quit, I gave it one more try, this time going back to the front page of SleepingBearBirdingTrail.org, and down on the right-hand side, there is a sidebar that says SBBT Area eBird Sightings. It’s updated daily, and shows when other people report birds in the Sleeping Bear region; think like a Twitter feed, but for birders. (Which actually makes a lot more sense, given the name of a Tweet, don’t you think?)

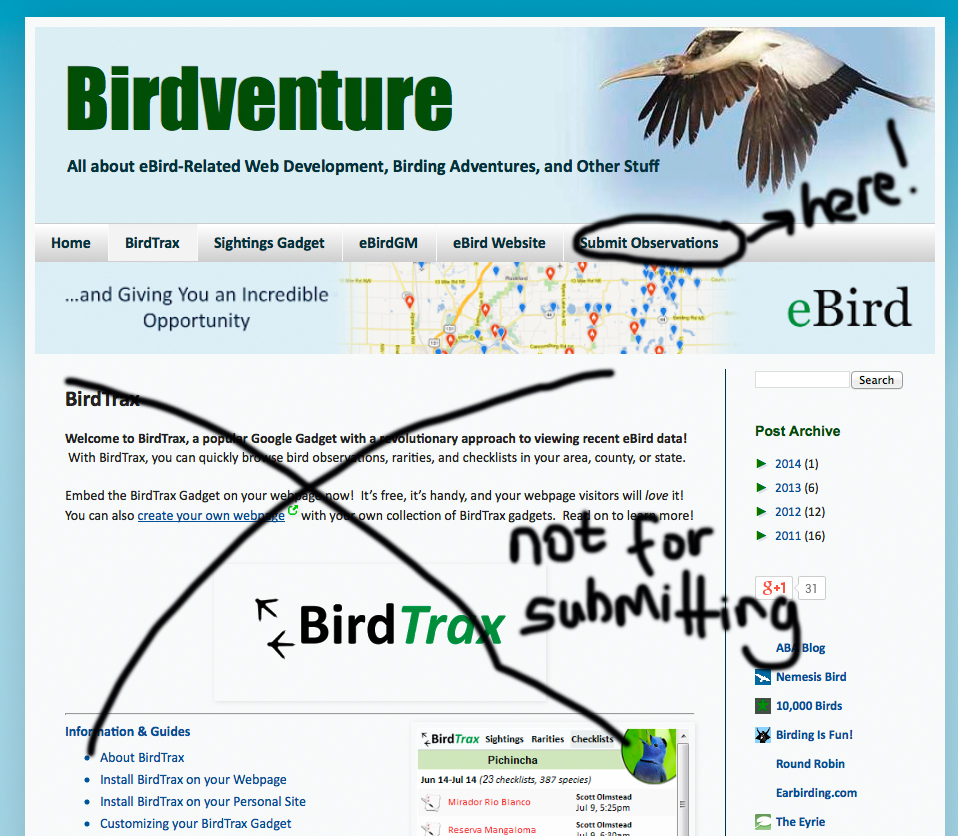

I clicked on the link there that reads “BirdTrax”, and it took me to another site, BirdventureBirding.com. Once again, however, I was a bit overwhelmed by the amount of text that was here describing the FAQs. What I wanted, instead, was a simple description of how to file a report. Instead, this page seemed to be telling me how to pull in this faux-Twitter feed onto my website. And the comments at the bottom from other users wasn’t much help either. It seemed that they were all birders, which I am not, and thus had very different questions than the simplicity of what I was looking for. Sigh.

But then I noticed Submit Observations in the top right-hand corner of the navigation bar, which took me to another site, ebird.org/ebird/submit. Finally, something that looked promising! The archive is apparently run by Audubon and a lab at Cornell University. Once you finally make it here, submitting your sighting is easy.

- You need to register for an account. All you need is first name, last name, email address, username, and password, but it’s nice if you want to give them a bit more info like where you work, your address, phone number, age, gender, education, occupation, and how you found their site.

- After you’ve registered and logged in, there are three ways to start. You can find your location on a map, use latitude/longitude, or select an entire city/county/state. Since I don’t know the latitude/longitude of our house (who does!?), I tried plugging in “Frankfort, Benzie, MI,” to the city/county/state option, but that came up with “We’re sorry, no location with that description could be found.” (I’m guessing that means that there are no registered “birding spots” in Frankfort, but I’m not really sure.) So then I tried the first option, “Find it on a map.” Again, I plugged in “Benzie, Michigan”, and a Google Map popped up.

- On this map, I was able to see the locations of where other people had reported birds. Red are “birding spots”, while blue are “personal locations.” The bigger icons are meant for if you were with a group when you saw your bird, and the smaller icons are for if you were alone. At the top of the map, you can enter your address, and the map will zoom way in. You then need to click on where you saw the bird. In this case, I clicked on where our house is in relation to the cross streets. A green marker will appear. (If you’ve clicked in the wrong spot by accident, just refresh the page and it will clear it so that you can start again from the zoom-ed out map.) On the right side, it asks you to name the location; in this case, I just put our address in. You can click a box below that says “Suggest as a Birding HotSpot” if it is not a personal location, but in my case, it was personal, so I did not click the box. Then click the green Continue button.

- Next, it wants you to give the date that you observed the bird. It also wants you to describe the setting: were you traveling or stationary, with the intent of birding, or was it an incidental occurrence, in which you just happened on a bird. (This was definitely the case for us.) More boxes will open based on this, in which the site wants you to fill in the start time and your party size — note that this means the number of people that were with you. I messed this up and put the number of birds that I saw, but I don’t think this is a huge deal since there were two of us and one bird, so I just put one. You can also leave comments here. I wrote a short little narrative about how we happened upon the bird.

“My boyfriend heard a noise upstairs in our 1901 house. The house is being renovated, and we’re not sure how the bird got inside… we’re guessing it’s through some open rafters or something. He almost gave up looking for the noise, but then he saw the Saw-Whet Owl sitting atop a mattress that was stacked in our hallway. He called me upstairs to help. We opened a couple of windows and briefly tried to flush it out, but that wasn’t working so well. (We also had to quarantine the area from the dog and the cat, who were very curious.) He took a towel and threw it on the owl, then picked it up by the back of the neck, more or less. He took it to the open window and stuck his arm, the towel, and the owl outside the window, and the owl promptly took off. It was very cool. Wish that we had thought to grab the camera, but we were more concerned for his safety — it had already been bumping around in our upstairs quite a bit before we found it. (We also used a flashlight to kind of blind it momentarily, so that it wouldn’t attack us — not sure if that would be an issue, but we wanted to make sure that we had the upper hand in that scenario. It was a raptor, after all.)”

- The next page that pops up is a checklist of birds, where you can input which birds you saw and how many of each. You can also click “add details” here, next to the species of bird that you are claiming that you saw.

That’s it. It’s that easy. (After you spend quite a good deal of time looking for this site, but hopefully you won’t have to, since I’ve done all of that for you.)

Look for Other Sightings of Your Bird

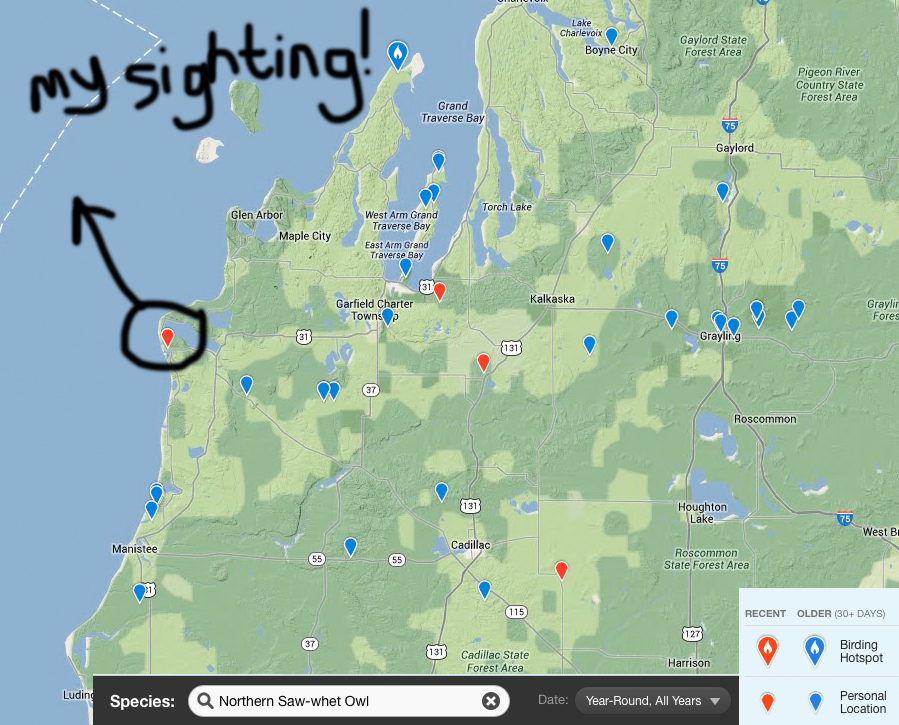

When you’re done submitting your sighting, you should play around a bit with the ebird tool. Click on Explore The Data in the navigation bar. Here, you can choose to explore a location, explore hot spots, range and point maps, bar charts, line graphs, and submission maps. I wanted to know if anyone else in Northern Michigan had seen a Saw-Whet owl recently, since the SleepingBearBirdingTrail.org site had said that they were very rare, so I chose to “explore a location.” This took me to another page, where I inputted my county and state.

To date, there have been 267 different bird species in Benzie County that have been submitted to ebird via 1,776 checklists of bird sightings. The default is to show you the latest seen, meaning that, if a bird has been seen multiple times, you are going to see a list of when the last time that each species was seen. If you click on “first seen”, it will show you when a particular bird species was first seen in Benzie County. Some of these sightings go back to 1971, which is pretty cool. You can also look at “high counts”, which shows when each species was seen with the highest number of its cohorts (for example, 80 Caspian Terns were seen together on May 14, 1999). You can also click on “bar charts” to see how frequent are the sightings of each bird. (Apparently Northern Saw-Whets havent been seen since August 2013 in Benzie County.)

You can click on each species of bird to find out specific details about it — there are graphs of frequency, abundance, birds, per hour, average count, high count, totals, map — or you can click on the “map” button beside each bird species to have a map come up of all the sightings of that bird within your location. The map of Saw-Whets in Benzie is pretty boring, just me and one other sighting. But the map of Saw-Whets in all of Michigan was much more interesting. This shows a graph of sightings of Saw-Whets throughout the state — looks like there are about 25 total sightings per week in Michigan for this time of year (if I’m reading these graphs correctly, which I’m not sure that I am). And here’s a great map to show where people have seen them over the years, too.

I zoomed in from the Michigan map to look at just Northern Michigan, and it looks like somebody *heard* a Saw-Whet in Grand Traverse County on February 20th, 2014, near their barn. Also someone saw one near the VASA trail on February 18th, 2014. In addition to the person who identified one near Crystal Mountain back on August 19th, 2013 (though I cant tell if it was an actual sighting or just that they heard it), there was a family in Karlin who was seeing one for three days at the end of September/early October of 2013, followed by their neighbor seeing one on October 2, 2013 (but they might have only heard it, I can’t tell from their notes). Seems to me that, besides these most recent sightings, there haven’t been many Northern Michigan sightings since 2009/10/11 (except for one sighting on Grand Traverse Peninsula in February of 2012 and two sightings in Manistee during November and December of 2013).

Could this all be the same bird, or is it likely to be many different birds? Good question. As I’ve mentioned, I left a message for the Sleeping Bear Birding Trail on their Facebook page, but I’ve also contacted the board members of the Audubon Society here in Benzie. Hopefully they can shed some more light on the situation.

And hopefully I’ve helped you to figure out the easiest way to identify and submit your sighting of a bird — be it out in the wild, or in your attic.

–Aubrey Ann Parker

Photographer for The Betsie Current

Note: The Betsie Current does not suggest attempting to remove a raptor, or any other bird, from your house by yourself. Contact your local DNR officer for help.