The absolutely imperative and thoroughly unsexy world of zoning, and why you should care

By Liz Negrau

Current Contributor

First of all, congratulations for intentionally starting to read an article about zoning. Just to be completely transparent on what you are getting into, please note that there will be no amusing anecdotes or photos of pets to incentivize your continued reading. What there will be is a mediocre and half-researched overview of zoning in Benzie County, as well as candid opining on potentially controversial zoning issues currently affecting our region.

Fair warning issued; so let’s get into it.

Zoning laws are regulations that govern the use of land. They can be used to restrict the types of buildings that can be built, the density of development (i.e. how close buildings can be built next to one another, and how tall those buildings can be), and the use of land for purposes such as commercial or residential or agricultural.

As thoughtfully put by Jeff Sandman, chair of the Homestead Township Planning Commission, planning and zoning is also “vital to the balancing act of creating access to affordable housing and doing it responsibly. With the help of a strong and experienced zoning administrator, an informed and thoughtful planning commission can pave the way for the right housing development for the community… while still putting various conditions on the project, which can protect the community and the integrity of planning and zoning.”

When done correctly, zoning can be instrumental in preserving the character of communities and providing for needed infrastructure, while at the same time… hnk…zzzzzzzzzzz…

Okay, maybe enough of the overview.

As interim executive director of the Frankfort Area Community Land Trust, I recently had the opportunity to speak on a panel—comprised of much wiser and more well-dressed individuals—addressing how zoning is impacting local communities’ abilities to build much-needed housing. The disparate and extremely well-informed panel speakers ranged from Tony Lentych, of the Traverse City Housing Commission and newly appointed chief housing investment officer for the Michigan State Housing Development Authority (MSHDA), to Ashley Hallady-Schmandt, director of the Northwest Michigan Coalition to End Homelessness. Other sage leaders included Yarrow Brown of Housing North and Wendy Irvin, CEO of Grand Traverse Habitat for Humanity.

What this panel had in common—besides our ability to snarf down about three dozen cookies in one sitting—was the daily effect of zoning regulations on our efforts to increase attainable housing in Northwest Michigan.

Zoning laws ostensibly exist for the greater community’s protection. Unfortunately, these complex and integral rules and regulations take years of planning and incredible resources—financial and otherwise—at the end of which, we have to show: a snoozefest of a PDF document. But a legal and binding snoozefest that governs every aspect of what and where you can build, in minutia.

But it’s not just the length and complexity of these documents—it’s also the quantity of them.

A Dozen Zones

More than a decade ago, Benzie County went from a county-wide zoning model to one in which each township, village, and city would administer its own zoning and planning. There are now 12 communities in Benzie County with their own zoning ordinances.

Additionally, we have zoning “overlays,” which provide an additional layer of zoning specifically designed to protect the unique character and natural resources of our communities. Examples of overlays include historic, conservation, floodplain/wetland, watershed, and agricultural.

While a number of organizations in Benzie County—like the Crystal Lake Watershed Association (CLWA), for example—have been formed specifically to advocate for and monitor our natural resources, the actual protection falls solely at the local government level, so Benzonia Township, Crystal Lake Township, Lake Township, etc. in the case of the lands that fall within the Crystal Lake Watershed.

Moreover, protective regulations and ordinances can fall within multiple governmental entities; for example, both a township and county, and possibly even state (like the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, or EGLE, formerly known as the Department of Environmental Quality, or the DEQ).

As a newish member of Frankfort’s Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA), I have had occasion to see how the historical complexity of these zoning PDF documents, as well as some outright laziness, can confound even seasoned architects and builders. Putting aside those who literally admit in ZBA meetings to not having read the zoning ordinances—it’s in the public record, folks—there still exists some ambiguity and legitimate reason for needing a zoning variance, hence the purpose of our board. But in general, modern “Planning and Zoning” is relatively accessible for the average citizen, and comprehension is furthered by copious examples, drawings, and easy-to-read charts.

But the complexities of zoning were not the topic of discussion for the Housing Panel that I attended in April, nor the topic of this article. Instead, I draw your attention to the ugly underbelly of zoning laws, namely when they become restrictive and outdated (at best) and potentially inequitable and discriminatory (at worst).

Inequitable zoning refers to the way that zoning can be used to create and maintain any type of segregation, but particularly racial and socio-economic. Because zoning laws are regulations that govern the use of land, they can be used to restrict the types of housing that can be built, the density of development, and even who can live in the homes.

As a seemingly innocent example, zoning can be used to create or prioritize “single-family zoning districts,” popularized during the 1950s and 1960s, when the first zoning “Master Plans” were created across the United States. Often, these are defined by spacious lots (one-quarter of an acre or more), with a single home on generous setbacks from the road and sidewalks. Benzie County has numerous communities built with this planning in mind, which was a workable and aesthetically pleasing neighborhood layout, especially for small towns, as they remained convenient to schools and businesses.

The 1960s-1990s era brought the influx of the suburban planning model, which called for even larger lots, enabled by the ownership of one or two cars for the average household. Hand-in-hand with these tracts, however, came less attractive regulations: deed restrictions, overly-empowered Home Owner Associations (HOAs), and exclusionary residential districts.

Then and Now

Zoning in Benzie County and in Northwest Michigan, while more rural and later to develop, also has a long history.

Benzie County as a governmental entity and location was “created” in 1863, and the first zoning ordinance in Benzie County was adopted in 1924. The ordinance was designed to protect the character of the community and to provide for public safety—untethered horses and the like, I guess, judging by the number of barns-cum-Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) still scattered around some of our century-year-old homes. Ordinances were amended several times over the years, with the newest being adopted in 2010 (with amendments), and goals increased to include promoting economic development and protecting the environment.

In no instances in my less-than-exhaustive research did I find an example of zoning becoming less restrictive.

This is about to change, however.

In the past few years, Benzie communities—in response to concerns about housing shortages and skyrocketing home prices—began researching ways to create what local nonprofit Housing North refers to as “Housing-Ready Communities.” According to the 2019 Northern Michigan Target Market Analysis cited by Housing North, Benzie County is projected to need an additional 703 housing units—ideally 425 rental units and 278 owned units—by 2025. (Note that this study was compiled pre-COVID-19. Housing North’s executive director, Yarrow Brown, has said we can add about 20 percent to that need, in a post-COVID world.)

Per Housing North’s toolkit, communities can start with a straightforward checklist that helps them to ascertain how prepared they are to welcome housing development.

Roughly half of the checklist pertains to zoning.

The other half includes questions on housing needs, community support, available funding, and the opaquely titled “Development Opportunities.” This section is the checklist’s meat and potatoes—probing the ease of accessing necessary forms and permits, identifying obstacles like lack of water or sewer access, and determining if appropriate infrastructure exists to support growth.

The document is both concise and widely applicable. It also stresses the importance—in multiple areas—of community backing. To wit, the plethora of recent examples of development planning being “presented” to local municipalities and communities, only to learn exactly how unwanted that development is.

“An informal introduction to the planning commission, at a regularly scheduled meeting, is a critical first step to explain the proposed development and to gain feedback,”as Jon Stimson, executive director of HomeStretch, recently put it. “It allows the public to have a record of the facts before any rumors are created. Valuable information is obtained by both parties, and subsequent presentations show how the development was tailored to the initial feedback.

The process used by HomeStretch, a non-profit housing developer based out of Traverse City, has proven to be a successful one, as the organization is now embarking on its third project in Benzie County in as many years. The continual feedback loop between government, citizens, and developer both increase trust and ensure new builds reflect community desires.

And integral to the whole process, start to finish, are the underlying zoning laws which (hopefully) have clearly defined the parameters for development, while also providing a robust process to apply for necessary variances.

In the current and worsening economic housing climate—and exacerbated by COVID-19 supply-chain issues and a newly mobile population, due to work-from-home dynamics—governments and communities both have been caught on their heels and are now in the undesirable position of having to consider emergency funding and approving these variances for much-needed housing.

Into this conflation come developers—most well-intentioned and looking to help solve the housing crisis, but also some predatory, whose missteps have caused distrust and have hurt those working for the betterment of the county.

The reasons for eschewing housing in any given community are myriad. Opponents may cite lack of trust in the developer or plans, inadequate infrastructure, environmental concerns, or development that is “out of character” for the proposed site.

But this is precisely why zoning exists.

Communities with clear zoning that welcome housing in their area are easily able to answer when asked where development might fit. It removes ambiguity and encourages responsible and sustainable development, and it also allows for upfront understanding of the type of homes welcomed.

Perhaps most importantly, however, the best Master Plan needs to account for future flexibility.

Planning in the Works

Art Jeannot, local developer and a Benzie County Commissioner (R), lists the following as imperative to developers when looking to partner with a community for housing:

“Flexibility in zoning variances, timeliness of permits and inspections, and relief from property taxes for multi-family rentals.”

Multi-family rentals, which are both superb for population density and relatively cost-effective to build, are often a target for NIMBYism (Not In My Backyard) and altogether forbidden from many zoning districts.

As for flexibility, it seems counterintuitive to make laws while specifically keeping in mind how they might need to change, but this is exactly the way that excellent planners think. Today’s housing crunch is a perfect example of the need for adaptation. And while COVID could not have been foreseen, many of the factors causing the current “housing shortage” in Northern Michigan have been in the works for years, well before the pandemic.

Small municipalities have the greatest ability to quickly react to changing dynamics. Townships and villages can consider, adopt, and/or approve a legit zoning variance, amendment, or Planned Unit Development (PUD) in half the time of larger cities.

Homestead Township recently advised neighboring townships that it will be updating its Master Plan, which is in need of revision since the township ended its joint zoning venture with Inland Township a few years ago, according to Jeff Sandman. In addition to the notice being legally required by Michigan Public Act 33 of 2008, it also seems to genuinely invite community feedback:

“Specifically, we welcome any input and concerns that you may have that would allow us to work more cooperatively with you in land use planning for our region.”

This is exactly the type of dialogue that kickstarts thorough and thoughtful planning, and if continued in this vein, could eventually lead to a consensus on where and how housing would be welcomed by Homestead Township community members, while providing clear guidance to local developers. In fact, Sandman specifically addressed housing when I reached out for more information.

“Throughout our Master Plan process—survey, open house, and meetings—there have been two major themes from the community: desire to retain the rural characteristics and the need for affordable housing. This echoes what I hear throughout the county on a daily basis. It’s great that there is a clear consensus, because to be successful, we will have to work together to overcome the challenges of organizing, finding resources, and overcoming a NIMBY culture which has somewhat grown over the years.” Expanding on this last point, Sandman stated, “It’s sad to hear from our neighbors who have been caught up in this mess. To think of how many families are spending their nights in tents and campers, simply because they can’t find housing in Benzie County; it’s a travesty. And it’s not just the summer. This is happening year round. They may not be sleeping in the streets, but they are essentially homeless. It will be a testament to the character of our community on how we respond to this crisis.”

Other Benzie villages and townships that are embarking on Master Plan journeys include the Village of Elberta, which is currently reviewing results from its March Master Plan survey. In true Elberta fashion, there will be a visioning session/open house on Thursday, June 15, from 4-6:30 p.m. at the Life Saving Station; the event will be focused on the Waterfront and Downtown districts and housing.

Similarly, the Crystal Lake Township Planning Commission is working on updates. Per Tom Kucera, zoning administrator for the township, they have recently updated the zoning ordinances. On the housing front, Kucera calls out that the current Crystal Lake Township Master Plan supports responsible residential development, and they are open to working with trusted organizations to develop middle-income housing, defined as housing that is affordable for people making between 60 percent and 120 percent of Benzie County’s Area Median Income (AMI), which is currently $56,760.

Kucera brings up an important point:

“The value of the property in close proximity to Crystal Lake is a primary factor preventing middle-income housing development. I believe this is true for Frankfort and Elberta, as well.”

The numbers back him up; the natural beauty and desirability of our region has caused housing prices in Benzie to skyrocket in 2021 and 2022, by 26 percent and 10 percent respectively.

But building properties further from these areas has its own set of challenges.

Many rural communities push back on housing developments, fearing a change in the character of the area. The type of home construction allowed by rural residential zoning typically allows only one single-family home per half-acre. Factoring in today’s costs to build wells, septic fields, driveways, roads, etc. makes it nearly impossible for an individual homeowner to build, even on an inexpensive parcel of land.

Kucera mentions another often overlooked consideration:

Rural properties must still “be able to connect to a reliable, robust internet, so the families living on those properties have access to education and to the virtual workplace.”

Frankfort’s Journey

The City of Frankfort—a population hub with a strong school district and other amenities that are attractive to families and developers alike—began seriously studying the housing crisis facing its citizens back in 2017, when they developed the Frankfort Area Housing Advisory Council. Determined to solve the lack of attainable workforce housing in the Frankfort area, a Housing Commission was formed through an ordinance adopted by the Frankfort City Council on June 25, 2020 and the creation of the non-profit Frankfort Area Community Land Trust (FACLT) just a year later, in 2021.

They also discovered that their lovingly crafted 2014 Zoning Ordinance had sections that were at odds with their goals for creating housing. In fact, although the Master Plan, last adopted in 2021, specifically supports attainable housing, no districts within the Ordinance passed Housing North’s checklist for “Housing Readiness.”

Despite this, the highly motivated Frankfort Housing Commission (FHC) and the FACLT will build, respectively, 12 to 16 rental townhome units and four to six single-family homes located in Frankfort over the next 18 months, and these projects enjoy huge community support. But it is worth calling out that both developments required multiple zoning variances.

You read that correctly—by the time this goes to press, two new homes will have been built, while the applicable zoning amendments that would have allowed them are still only in draft form, thus necessitating variances for them to be built.

“The wheels of justice and government turn slowly, but grind exceedingly fine.” Couldn’t have said it better myself, Sun Tzu.

Why So Hard?

So if the community wants the housing, why do we make it so hard? It does not have to be, and this recognition wrought the creation in 2022 of Frankfort’s ad hoc Zoning Ordinance Amendments Committee (ZOAC), bringing us back to the aforementioned changes that are in store for our area.

The goal of the Frankfort ZOAC was to see what, if any, “tweaks” could be made to the Master Plan to encourage workforce housing within the city limits.

In Benzie County, Frankfort is unique in its existing or easily expanded infrastructure, like the ever-important and easily overlooked sewer and water, electric, roads, sidewalks, and other utilities, not to mention decent walking distance pretty much everywhere—unless it’s February. (Yes, I’ve driven the 45 feet to my mailbox; don’t judge.)

The ZOAC—on which I serve as a ZBA member, along with three members of the Frankfort Planning Commission, City Mayor JoAnn Holwerda, and other residents—has already completed a Seasonal Workforce Zoning Ordinance Amendment, which was presented at a public hearing on April 13. This amendment would allow for easily-erected seasonal-workforce housing units, such as ancillary dwelling units, travel trailers, RVs, tiny houses on wheels, or other approved temporary structures in limited locations throughout the city.

Yes: Frankfort is at the point where, to fill the housing gaps, they are going to allow people to live in temporary dwellings, essentially camping out within the city limits. At least from May to October.

For year-round workforce residential needs, they are also working on Article 8 of the City’s Master Plan, which would increase population density and create more attainable housing by allowing for development of previously disallowed housing types, like duplexes, mixed-use buildings, cottage court communities, and townhomes, all cleverly designed to preserve and blend with the character of existing neighborhoods.

Per Jay White, an FHC and FACLT member who also serves on the ZOAC:

“The land area of the City is approximately one square mile, with most of that area already built out. This Attainable Workforce Housing Article will… make the most of the vacant and infill land that is available and, at the same time, conform to the current zoning ordinance in terms of lot coverage and aesthetic appeal. An important provision of this article is that each dwelling project will need to qualify as attainable workforce housing within initial income limits for those homeowners and tenants.”

In short, the housing allowed by Article 8 is specifically for and limited to year-round residents of Benzie County, protecting it from the stiff competition of summer-home-buyers and short-term-rental business owners.

Role of the Community

The community plays an important role in shaping the future of zoning in Benzie County. Getting involved in the zoning process is the best way residents can help to ensure that zoning regulations are fair and equitable.

On May 10, Weldon Township’s Planning Commission held a public meeting regarding a new proposed Planned Unit Development (PUD). The meeting was one of many steps in the fact-finding and approval process, and it was focused solely on the allowable land use decision put to the Commission.

Despite the limited scope for the evening’s decision, the feedback from the community was as varied as the community itself, with statements ranging from “we need any housing we can get” to “I don’t understand how this is going to benefit me.” What everyone could agree on, however, was what Timothy A. Cypher, Weldon Township Zoning Administrator, stated shortly before the public comments section:

“It’s great to see township citizens come to speak on these matters. It’s a welcome sight to see a full room.”

There are a number of ways that the community can get involved in the zoning process, beyond speaking at meetings and hearings. Submitting comments on proposed zoning is just as effective, as these are typically read verbatim into the records.

Lastly, it’s worth considering running for local office or participating on a local board. Master Plans are legally required to be reviewed every five years, and most municipalities reimburse board members for any virtual or in-person training needed. (I have availed myself of this twice; once in an out-of-state Planning and Zoning citizen workshop, and most recently via Michigan State University’s online program, where I am studying to get my second Zoning Board of Appeals Certificate.)

The best way to ensure that zoning regulations reflect the values of the community are to simply show up and get involved.

It’s your turn to bring the cookies.

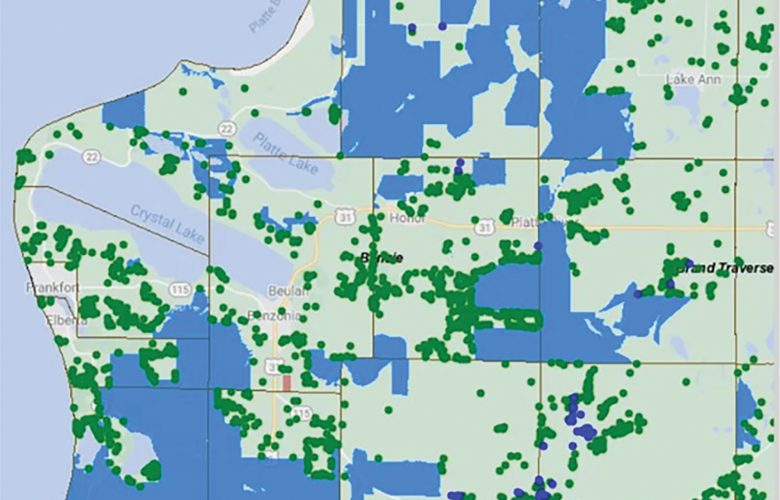

Featured Photo Caption: According to the 2019 Northern Michigan Target Market Analysis cited by Housing North, Benzie County is projected to need an additional 703 housing units—ideally 425 rental units and 278 owned units—by 2025, though that number is actually likely to be 20 percent higher in a post-COVID world. So, the highly motivated Frankfort Housing Commission and the Frankfort Area Community Land Trust will build, respectively, 12 to 16 rental townhome units and four to six single-family homes located in Frankfort over the next 18 months, and these projects enjoy huge community support. Two of the single-family homes are pictured here. But it is worth calling out that both developments required multiple zoning variances. Photo by Liz Negrau.

————

SIDEBAR

Pros and Cons

Developing Housing in Rural Areas

Few responsible developers are turned down outright on their proposals. The fact is, developers do not bring projects to municipalities until they have already passed a stringent internal test, including a thorough market study reflecting local demand. Developers also do not usually build exactly what they first present.

Responsible development is a process, and final results often have community-led improvements, such as more vegetation buffers, increased safety signage or lights, rainwater collection systems, and aesthetic changes.

The goal for developers and communities alike should not be to find the perfect development in the perfect place; rather, it is to find a workable compromise on the best available location.

For example, an objection to rural development, in particular, might sound like: “That corner’s not safe. People drive too fast. Find somewhere else.”

While this may be true, it should not serve as a dealbreaker. The community and developer are better served to work together: “Okay, how can we make it safer?”

Similarly, developers need to be thinking about how to incorporate the community in every step of their planning.

For instance, many developers prefer to use the same crews and subcontractors, sometimes even bringing in teams from out of state, due to it being easier or more cost effective. This can also compound the housing issue—where are these out-of-state workers going to live while they are working on the project? “Okay,” says our hypothetical community, “But what about using David’s A-1 Plumbing? They’ve been in our area for years, and he has a team of eight local employees.”

Pros:

• Job creation, which can help to boost the local economy.

• Increased tax revenue, which can be used to fund schools, roads, and other essential services.

• Increased population, which can help to revitalize rural communities and make them more attractive to new businesses and residents.

• Improved infrastructure, such as roads, water, and sewer systems, as well as broadband internet connections (consider, Dear Reader, life without Netflix—is this the kind of hellscape that we are willing to inflict on our neighbors?!?!)

• Access to amenities, such as grocery stores, hospitals, and schools.

Cons:

• Environmental impact, such as by polluting waterways, destroying forests, and fragmenting wildlife habitat.

• Increased traffic, which can also increase the risk of accidents and make it more difficult for children to get to school and for people to get to work.

• Loss of agricultural land. Not as much of a threat in Benzie, which has ample vacant and fallow land. But in other rural counties, it could have a negative impact on the agricultural economy.

• Increased demand for services, such as schools, hospitals, and roads.

• Loss of rural character, which is problematic for those who value the peace and quiet of rural life.

Thank you Liz Negrau for this thoughtful well researched article. Yes I read the whole thing! I did because it is clear , relatively easy to grasp and at times funny. I am not alone in having concerns about how and where we develop but I know that it is necessary.Not only that,I want a community that is home to more young families and single people. Folks just starting out in their careers and well established entrepreneurs. The suggestions to show up with an open mind, run for office and become more educated are all important suggestions. Zoning is not or should not be the job of the elusive “someone else”. It is our job to participate in the creation of a community that reflects our best knowledge and dreams. And you get cookies !!! Thanks you Liz and Betsy Current for creating a template on zoning that we can refer again and again.

I read it top to bottom! Kudos to you for providing a clear explanation and update to local zoning issues and progress. I can’t wait to read an update!