instruments hold life lessons on aging

by Crispin Campbell

I am 55 years old, and enjoying the tail end of a yearlong sabbatical from teaching the cello. I have concluded that the concept of ·sabbatical” is probably the greatest achievement of Western Civilization. Just think about it: a year off work, with enough money to pay rent and eat, and all the time in the world to think, and to not be busy. So, what have I been doing, while I’m not being busy? Thinking. About what? Age.

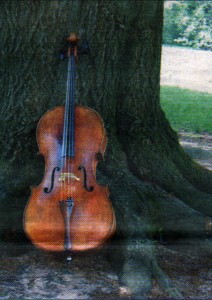

I just visited my cello teacher from graduate school, George Sopkin, who is 92 and still working. He is getting old for a human, but in cello terms is rather young. My own cello is 159 years old, and sounds great (when I practice). But, we (humans, and cellos) are all in the same boat – the vessel of time. The minutes tick by, and we get older. Of course, the big question is: why do we age? Perhaps contemplating what makes a cello sound beautiful will shed some enlightenment on this age-old question.

As a professional cellist, I am fascinated with the qualities found in string instruments, specifically violins and cellos. These boxes are made of wood, glue and varnish; all natural, organic

substances. Some say these instruments are are like people, with unique personalities and subject to the same laws of nature. And it is also true, a fine instrument that is well cared-for will improve with age.

It takes a while for this new configuration of cells to find its voice. In a few months it will sound pretty well – the wood gets used to vibrating as a unit. Of course, there are almost an infinite number of variables that affect the sound: thickness of wood, kind of strings, thickness and quality of varnish, kind of rosin, weight of the bow, weight of the tailpiece, height of the bridge, thickness of the bridge, and on and on. Then there are the qualities of the player (or lack thereof) that are too numerous to list, but I’ll mention just one: the ability to play in tune.

If an instrument is played beautifully in tune, it will resonate with a fuller, richer sound than the same instrument played just slightly out of tune. This has to do with the overtone series, the ratios of the division of a string, first attributed to Pythagoras (6th century B.C.E.). So, if an instrument is played, used as a tool for music making, for 15 hours per week, when will it “grow up?” Each instrument is different, but after five years, an instrument will sound appreciably warmer and richer, after 30 years perhaps even better. The truth is, it is more a matter of how the instrument is treated: regular trips adjustments, no abuse, and plenty of use. If an instrument is not played, it will go dormant, and lose its beauty of sound.

The great instruments of Stradivari; Guarneri, Montagnana and other Italian makers are all nearly 300 years old. At that age, many instruments need some major attention, but can have many years of playing still in them. Even some of the most abused instruments can be restored. The “ex Paganini Countess Stanlein” cello was found in pieces in a wheelbarrow in Milan. Old cellos are often given the names of previous owners and the engaging and informative short book by Nicholas Delbanco, “The Countess of Stanlein Restored,” documents the story and is worth the price ($12.99).

A few years ago I attended a birthday party in Ann Arbor for another cello: “The Duke of Edinburgh; an instrument made by David Techler in 1703 and owned by Anthony Elliott, professor of cello at the University of Michigan. This instrument was a wedding gift to the husband of Queen Victoria of England from the Commonwealth member state Australia, in the 19th Century. The party included several concerts of cello music, master classes, and a lecture given by the cello itself (in Prof. Elliott’s voice) about its life and journeys.

So, what is to be concluded about these old instruments? They get better with use and good care. They can be restored. They can give great pleasure and meaning to those who listen. Since we are all aging, the lesson for us is clear: keep doing what we love, take good care of ourselves, give ourselves time for restoration and our lives will be richer and fuller, and in “tune:’ And perhaps we should remember the sage advice of George Sopkin, still playing in tune at age 92, “Don’t you ever retire! Why would you want to?”

This article was originally published in 2006. George Sopkin died at age 94 at his home in Surry, Maine in 2008.

Omg this makes my heart sing only notes my cello can play. I just picked up playing my cello this past April after taking a decade off from playing. Your totally great Cris hope you come to Tucson to play one day.