Copemish Depot finds new home near Glen Arbor

By F. Josephine Arrowood

Current Contributor

There is a painted lady in Glen Arbor, setting heads a-swivel as they walk, bike, or drive past Bay Lane at M-22. Although diminutive at under 700 square feet, she has an outsized personality. She is well-traveled for her age—at least 125 years—and her pedigree is just as colorful as her painted trim, ornate corbels, and drop finials.

For more than five decades, she has been hiding in plain sight in the former Wildflowers retail compound on South Glen Lake Road. In the spring of 2021, she began a new chapter as the private residence of a family with an abiding affection for the Glen Arbor area.

“She” wears a sign proclaiming herself the Copemish Depot. But Copemish, a sleepy village in northeastern Manistee County, is a solid 50 miles away, and no rail service requiring a passenger station was ever erected in Glen Arbor—a line was planned from Cedar City in the 1920s, but was instead diverted to Provemont, now known as the village of Lake Leelanau.

So, what is the connection between Glen Arbor and the charming little depot from Copemish?

Her story began when railroads were king and the lumber boom made fortunes in much of Northern Michigan. In 1889, two rail companies—the Frankfort & Southeastern (which would later become part of the Ann Arbor Railroad) and the Chicago & Western Michigan (later the Pere Marquette)—created a railroad intersection called a “diamond crossing”* in southern Benzie County. This mechanical innovation would efficiently connect people and goods from Northern Michigan, the Upper Peninsula, and Wisconsin with Grand Rapids, Chicago, Ann Arbor, Detroit, and Ohio.

The hub quickly became a settlement known as Thompsonville; by 1900, it was known as the “biggest little town in Michigan.” Its two depots, situated across from each other on the diamond, oversaw not only materials and products, but also tourists who flocked to resorts at Frankfort, Crystal Lake, Traverse City, Solon, Provemont, and beyond. The pretty painted lady, owned by the Ann Arbor Railroad, sat east of the tracks, adjacent to the so-called “switch tower,” a ground-interlocking machine in a shed that facilitated the movement of trains from one rail line to another.

Other towns along these rail routes thrived during the lumber era, too, including Copemish, situated about four miles southeast of Thompsonville, just over the Benzie-Manistee county line. But in 1917, Copemish’s original depot, also built around 1891, burned. The painted lady thus made the journey—appropriately by rail—from Thompsonville to her second home at Copemish’s own diamond crossing (one railroad ran to Manistee), where she continued to greet passengers for the next 48 years.

As the lumber era came to a close, and automobiles became more numerous and affordable after World War II, train services diminished—as did many small towns along their routes. By the early 1960s, the Ann Arbor Railroad maintained a freight operation through Copemish but no longer offered passenger train services.

So it was that, in August 1965, the decommissioned depot made the 50-mile trip on a flatbed trailer to the village of Glen Arbor. The painted lady—a bit tattered, but still recognizable in her simplified ball-and-dowel spandrel brackets, projecting gabled ticket bay, and tall, two-over-two windows—was the ultimate antiquing find for Virginia Hinton and Charlene Baker, owners of The Country Store.

Virginia Hinton taught at The Leelanau School in Glen Arbor; she was also a certified gemologist and an early mentor of local jewelry designer Becky Thatcher. According to a newspaper article of the time, The Country Store was a gift shop “designed in the manner of an old-fashioned store, …furnished with original antiques, including a potbellied stove, cracker barrel, coffee mill, and an old cash register.” Despite the lack of railroad tracks, the painted lady from Copemish would fit right in, welcoming the many visitors who would exclaim over her well-formed timbers, beadboard paneling, and colorful embellishments.

In 1980, Donna Burgan bought the complex and created Wildflowers: a gift shop, garden center, and design studio that flourished for 40 years; a tranquil oasis adjoining the village’s increasingly bustling tourism.

As Wildflowers grew, so too did the visual clutter surrounding the painted lady, obscuring her Carpenter Gothic-inspired details behind the main store building, extensive gardens, landscaping inventory, and Christmas decor. At some point, whether as part of The Country Store or Wildflowers, extra doors were cut into her original side façades, and additional alterations were created—perhaps necessary to a retail business but not in keeping with the lady’s historical harmonious appearance.

Burgan decided to retire in 2019, and eventually the property was sold to a developer with plans to build condominiums on the site. Wildflower’s devoted customers made their final pilgrimages to the shop. Among them was Cynthia Badan, a longtime seasonal resident whose parents had first introduced her to Glen Arbor and who had nurtured her own decades-long love affair with the blue waters of Sleeping Bear Bay.

“My parents, Richard and Mimsy Harder, worked at The Leelanau School,” she explains. “On every special occasion, my mom used to take me to Wildflowers. Last year, her birthday was coming up. I thought I’d get one more thing from Wildflowers before it closed—it was the end of an era.”

That “one more thing” ended up being pretty unconventional—as Badan strolled the grounds, she came upon a building she had never noticed before.

“I think it was where Donna [Burgan] had her Christmas displays—but I’m a summer person, and I’d never been in there,” Baden says. “The sales girl said, ‘Everything is for sale: the actual building is for sale!’”

Baden felt that she could not pass this up.

“I called my [adult] kids; three of them were in Glen Arbor,” she recalls. “I asked them to come over and look at the depot. I had a crazy idea.”

For 25 years, Badan, along with her kids and then-husband, had had a place on Sleeping Bear Bay. Lake Michigan was her touchstone, a place she had fallen in love with when her parents came to The Leelanau School in the mid-1980s. Her father was assistant headmaster and development director, while her mother worked in the alumni relations office.

“They lived on Faculty Row, but they knew everyone in town, too,” Baden recalls. “They’d go to the ‘Board Meetings’ at the WAG [Western Ave Grill] every Thursday. They knew Norm Wheeler, the Rockwoods.”

The educators’ previous career moves had taken them from New York to St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands when Badan was just four years old.

“Every day for eight years, I could look out the window of my school in St. Croix and see that blue water,” she says. “In eighth grade, we moved to Lake Forest, Illinois, on Lake Michigan, but the colors and the feel of the water were completely different. When I was in college, Dad took the job in Glen Arbor, and he sent me pictures of the lake here. I was like, ‘This is unbelievable—it’s just like St. Croix.’”

Badan continues:

“My brother and I are both very attached to water; the lake and the ocean. In St. Croix, our parents wanted to give us kids a cultural experience, but their friends and their parents gave them a lot of push back at the time. Now, they live in Maine. They don’t return to the old places where they’ve lived—they’ve only come back to Glen Arbor a couple of times—but they’re happy to think that they helped to create a place for us.”

In Northern Michigan, Baden feels a deep connection to sand, waves, and sky, like those in her Caribbean memories, and she values a place to nurture that sense of belonging for her own children, as well.

Five years ago, the family needed to sell their home on Sleeping Bear Bay, and it was very emotional. Since then, they had been renting for several weeks each summer—which can be quite expensive for a middle-school French teacher.

At Wildflowers, on that fateful day last year, Baden’s crazy idea took shape.

“What if my kids and I bought this [depot], and put it on a little scrap of land, and put into it all the money we would have spent on an expensive summer rental for the next five years?” she says. “I told Donna [Burgan] the whole story, and she loved it. We worked out a deal, we shook on it, I gave her five dollars in earnest money.”

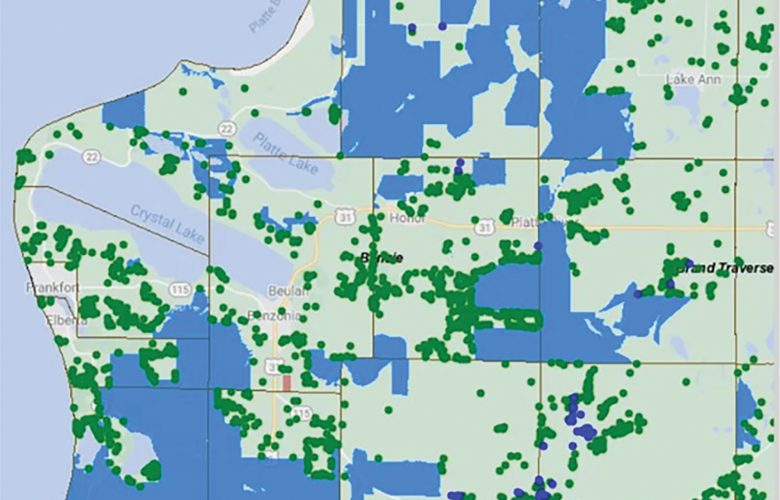

Last fall, Badan also closed on an undeveloped half-acre of land situated near the oxbow of the Crystal River, where Bay Lane meets M-22 and County Road 675. The painted lady carries a tiny footprint that fits well in the site—only 680 square feet, and Badan will have to add just shy of 400 square feet to meet Glen Arbor Township zoning regulations for a single-family dwelling. But she is thrilled with her family’s new adventure—three of her four children are involved in the project—and the chance to create even more connections with the Glen Arbor community.

This spring, builder Tim Newman of Kasson Contracting in Maple City moved the historic depot a fourth—and hopefully, final—time from the Wildflowers site to her new location. The roof had to be removed in order for the lady to make her stately way along M-22, and a rubber membrane was installed to keep weather out, but the graceful rafters with their distinctive pitch will be reinstalled this fall.

Newman has already removed later additions—like puzzling barn-style doors—and restored the window openings, whose original trim caps could still be seen above the crude alterations.

“He is a real treasure,” Baden says of Newman. “A real master craftsman; his handshake is his word.”

Architect Robin Johnson—who, with her husband, Robert Foulkes, and Cherry Republic owner Bob Sutherland developed the New Neighborhood in Empire 30 years ago—is assisting with the vision for restoring and rejuvenating the painted lady.

“She had helped us with our old bay cottage, and we reconnected last summer,” Badan says. “Robin loves historic buildings. She is an invaluable resource; taking the space that’s there, keeping what is good, preserving the charm. The building is so thick, so solid, with elegant proportions and details, like the brackets. With its 14- to 16-foot ceilings, it feels so much bigger than it is.”

Of the proposed plans, Badan says:

“At first, we had a very different vision. But now we’re back to the simple plan. The building is basically three rooms: we’ll keep the waiting room exactly as it was—we sealed up where the doors and windows had been moved around; someone had lowered the floor in one area for some reason. That will be the living room. The middle room, where the ticket booth was, is pretty much intact, and we’re keeping it that way. Maybe the future dining room? Keep the original windows, figure out how to make the building energy efficient. The room at the end—luggage room or cafeteria or whatever it was—we’re not sure yet what we’ll do there. The additional 400 square feet will be in the back.”

She laughs: “Now it will shine again!”

A version of this article first published in the Glen Arbor Sun, a Leelanau County-based semi-sister publication to The Betsie Current. The author wishes to thank Charles Kraus of the Benzie Area Historical Society for his extensive research on the history of Thompsonville.

*Back in our October 8, 2020, issue, The Betsie Current published Kraus’s article about the Diamond Crossing in Thompsonville; additionally, we have previously published a series of articles on the railroads, the car ferry, and their significant contributions to the area’s tourism industry, as well as a profile of James M. Ashley—former congressman from Ohio, former governor of the Montana Territory, noted abolitionist, and member of the radical wing of the Republican Party—whose post-Civil War dream was to begin a cross-lake rail car ferry service that would bypass the rail congestion of Chicago. Read the series in our online archives.

Feature Photo Caption: The Copemish Depot has been moved several times over its 125-year history. The most recent move is to a half-acre of land on the Crystal River in Glen Arbor, where Cynthia Badan, a longtime season resident, and her adult children intend to use it as dwelling. Photo courtesy of the Glen Arbor Sun.

SIDEBAR

History of Painted Ladies

“Painted ladies” are Victorian and Edwardian* houses and buildings that have been repainted—starting in the 1960s—in at least three colors that embellish or enhance their architectural details. The term was first used in 1978 by writers Elizabeth Pomada and Michael Larsen to describe San Francisco’s Victorian houses.

Although multi-color decoration was common during the era, the colors used on these houses now are not considered to be historical precedent: according to Wikipedia, there were about 48,000 houses in the Victorian and Edwardian styles that had been built in San Francisco between 1849 and 1915, and many were painted in bright colors.

“Everything that is loud is in fashion… if the upper stories are not of red or blue … they are painted up into uncouth panels of yellow and brown…” wrote one newspaper critic in 1885.

Many San Francisco mansions were destroyed in the 1906 earthquake, but thousands of the more modest homes in the western and southern parts of the city survived, and many of these houses were painted battleship gray during the early part of the 20th century, thanks to surplus Navy paint from the world wars.

Then, in 1963, San Francisco artist Butch Kardum began combining intense blues and greens on his Italianate-style Victorian house. Despite that his choice in paint colors was criticized by some, other neighbors began to copy the bright colors on their own houses; Kardum became a color designer, and he and other artists/colorists began to transform dozens of gray houses into Painted Ladies.

By the 1970s, the colorist movement, as it was called, had changed entire streets and neighborhoods, not just in San Francisco, but across the United States.

*The change from Victorian to Edwardian style occurred on the death of Queen Victoria in 1901.

Ms. Baden–Cynthia Baden, you must have attended The Good Hope School, Frederiksted, VI. I loved teaching at GHS for a number of years–the Caribbean Sea directly outside my classroom windows. At one time it was a hotel owned by Leon Hess and Laurence Rockefeller, then became a private school grades K-12. Unfortunately, when Hess Oil Refinery vacated the island in 2012-13, many Good Hope families returned to the mainland. St Croix Country Day and Good Hope merged, the campus is now Mid-Island.