A brief, golden age of Frankfort… but not the last

By Jed Jewarski

Current Contributor

The lore and romance of the late 19th and early 20th-century resort hotels easily inspire romantic and nostalgic images. Mackinac Island’s Grand Hotel and the 1980 film release of Somewhere in Time come to mind, influencing many Michiganders’ perceptions.

It was a time like no other: the Edwardian era. The industrial revolution had brought seemingly endless possibilities for society and our built environment. Guglielmo Marconi had invented wireless radio telegraphy. Travelers could cross the Atlantic Ocean in just days aboard luxurious liners. The last unexplored place on the planet, the South Pole, was visited for the first time. It was a period of great vibrancy; there were no wars, and the stuffiness of the Victorian era was now fading into the past.

Not only were there technological advances, but the new century came with great social changes, too. Women would soon be able to vote, and even as the titans of industry were consolidating power and luxury, there was a new, exhilarating upward mobility for the working class.

Here in Benzie County, the changes wrought by this era generally came slowly and in subtle ways, but dramatic change was about to arrive here, as well.

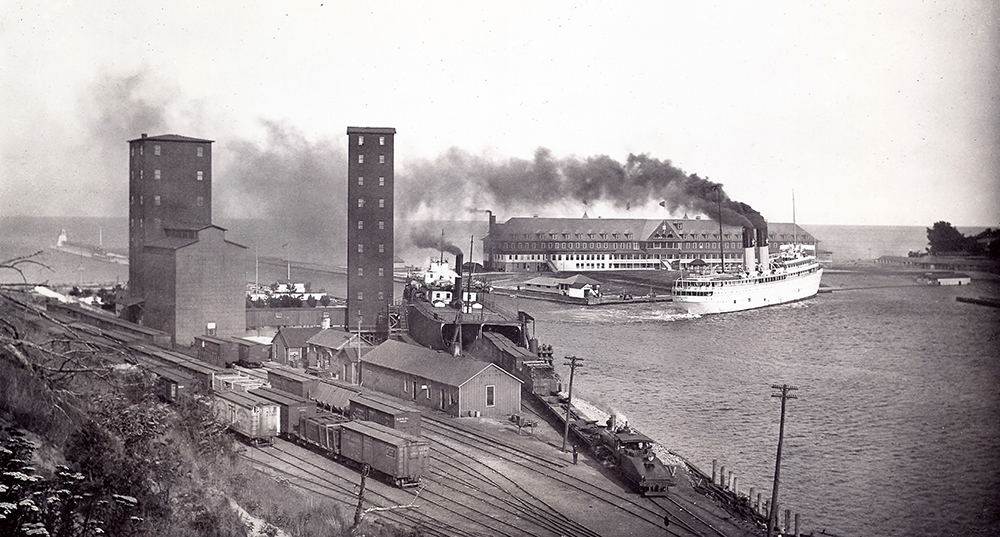

Within less than a decade, modern ships and railroads would be bringing throngs of people from afar. The tallest building north of Grand Rapids would be built here—a grain elevator—as well as one of the largest and most modern resort hotels on the Great Lakes.

To preface that, James Mitchell Ashley and his Ann Arbor Railroad Company wanted to build a railroad across Lake Michigan and chose the Frankfort/Elberta harbor as its shore terminus. Ashley had a reputation for thinking big. A man of strong moral conviction, he served in the House of Representatives for Ohio during the Civil War, was a personal friend of President Abraham Lincoln, and helped to draft the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery.

In the “anything is possible” spirit of the time, Ashley envisioned technologically advanced ice-breaking “train ferries” carrying passengers and rail cars where railroad tracks could not—across the storm-tossed and ice-covered waters of Lake Michigan. Always an innovator, Ashley had been originally inspired by the Michigan Central Railroad’s use of ferries at the seven-mile Straits of Mackinac, but his ferry crossings would be longer, more arduous, and much more dangerous, given that the Ann Arbor routes took them on more than 200 miles of the open and unprotected lake.

By 1892, Ashley’s 294-mile track of railroad was complete from Toledo, Ohio, to Frankfort/Elberta and his fleet of ships successfully began plying the waters to Wisconsin. Now within reach were the rich resources of the Midwest—the timber that was coming out of the forests, the iron ore range of northeastern Wisconsin and the western Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and the wheat fields of the Great Plains states.

Another big reason for the route was to provide a faster and more economical alternative, compared to running freight through the rail yards of Chicago; at the time, railcars would take days or even weeks to travel through the busy Chicago yards, since a majority of east-west rail traffic was routed through Chicago.

A byproduct of industrialization at this time was that cities were becoming crowded and unhealthy. Increasingly, more Americans could now afford to make an escape via trains and steamships to regional areas with fresh air and clean waters. The Ann Arbor Railroad, having both ships and trains, recognized an opportunity in Frankfort/Elberta’s quaint size and stunning natural beauty to offer just such an escape—sure, the railroad offered a way for Benzie residents to more readily travel the greater world, but the real money-maker would be more people from “the outside” coming in.

So, in 1897, planning began for a railroad-owned destination resort on Frankfort’s waterfront. John Kirby, general passenger agent for the Ann Arbor Railroad, was tasked with the job of promoting the resort. The railroad acquired land between Betsie Bay (then called “Betsie Lake”) and Lake Michigan and also between Crystal Lake and Lake Michigan.

A contest was publicized to help find the ideal name for the hotel, and several thousand responses were received. The choice of “Frontenac” was selected, because Louis Frontenac, Governor of New France—the North American area colonized by France from 1534 to 1763 which extended from modern-day Newfoundland to New Orleans—provided the means for French missionary and explorer Father Jacques Marquette’s 17th-century travels.

“Royal” was added to the name for prestige: the Royal Frontenac Hotel.

The Frankfort side of Betsie Lake was chosen as the site for the hotel, despite some inherent challenges. Betsie Lake originally flowed into Lake Michigan on the north side of the harbor, near where Cannon Park is now, at the west end of Main Street. A new, deep channel for accommodating ships had been dug on the south side in 1867. This had left a strip of land between Betsie Lake and Lake Michigan, with a deep channel on the south side, a high wooded dune in the middle, and a now dried river bed to the north. With channels now on both sides, the area became known as “The Island.” (This area, near Harbor Lights Resort, is now marked with a plaque where Father Marquette is said to have died and been buried in 1675, according to some sources. This is disputed, however, as some scholars believe the location to be Ludington; check our online archives to read more about Frankfort’s connection to Father Marquette in a June 2020 article.)

Again, this was a time when mastery over nature was thought possible, in part because of the machines of the industrial revolution—but there would be no modern machines employed in site development for the new hotel.

Rather, beginning in 1900, a force of 16 teams of two horses with one driver and a scraper shovel worked seemingly endlessly to haul away the 100-foot-high dune, depositing it as fill in the old river channel and then grading the site. After at long last clearing the location for the structure, the leveling work over the hotel grounds continued, as the cement layers and carpenters began work erecting the structure.

The Detroit-based Mason and Rice architectural firm that designed Mackinac Island’s Grand Hotel is said to also have designed the Royal Frontenac. However, it is certain that the construction contract was awarded to Charles Hoertz & Son of Grand Rapids. Hoertz was described as first arriving in Grand Rapids “without material asset, friend or money, but plenty of pep and ambition to someday be a contractor.” As Hoertz’s aspirations began to be realized, he must have been very pleased to have been awarded the contract to build one of the most prominent resort hotels in the Midwest. His ambitions likely dampened, though, when, on January 16, 1901, a fierce Lake Michigan storm blew the partially completed structure to the ground. Hoertz, however, was undaunted, and set right back to work. His can-do spirit and congeniality gained him a very favorable reputation, which served his career well, as he went on to build many prominent and notable commercial structures throughout Michigan over his lifetime.

Finally on July 1, 1902, the construction laborers ended their herculean task, and the new hotel staff opened the Royal Frontenac.

The hotel was not only impressive to locals, but to travelers far and wide. Set on the narrow strip of land between two bodies of water and at the center of the harbor, it was an imposing structure with lake views from all sides. At 500 feet in length and 100 feet in width, it extended four stories high and had a full-covered, walk-around porch on the main level. Large staircases flowed from the upper promenade to the grounds and beach; inside, an elevator offered a novel way to get from the ground floor to your lofty room.

The Hotel Frontenac offered modern amenities in the 250 private rooms: electricity, plumbing—including hot and cold water—and, to much amazement, a telephone in every room. On the first floor were stores, a large bar, a game room, and a cigar shop. It had a beautiful dining room with large French pane windows. The coal heating plant, laundry, and mechanical systems were housed in a brick ground-level area on the south end.

An unusual discovery was on display in the hotel’s lobby—an 11-inch-tall gold altar crucifix and human skull, said to have been unearthed when excavating the dune. These were attributed to Father Marquette, though that was never verified, and the newsworthy discovery of national interest was used by the railroad unabashedly to promote awareness of its hotel while under construction.

The allure of the new hotel remained unabated. By July 26—less than a month after opening—the Frankfort lighthouse keeper’s log entry noted that 1,200 people had arrived in town by train and aboard the S.S. Pere Marquette #3 to visit the hotel. It was not uncommon to have 12 full passenger cars arrive at the train station, near the west end of Main Street, with passengers thrilling at their first views of their new-found water wonderland and magnificent hotel.

The resort was as envisioned: society notables occasionally booked, the young ladies from cities near and far with their long dresses and parasols walked, escorted by gentlemen, along the beautiful promenade. Above, open guestroom window curtains danced in a gentle and pleasing lake breeze. Children played on the white sand beach and splashed in the cool, clear water. There were romances and summer memories made to last a lifetime.

The natural beauty of the area and the magnificent hotel were also noted by a newly arrived pastor, Reverend John H. Hull, at the Frankfort Congregational Church. Congregationalists in the Midwest had been looking for a location for a summer Bible retreat. After an unfortunate camp retreat near New Buffalo, Michigan, where attendees were “nearly devoured” by mosquitos from a nearby swamp, Hull suggested considering the Frankfort area and its pleasant lake breezes.

Consideration was indeed made, and Congregational representatives were invited in 1904 to travel with John Kirby—general passenger agent for the Ann Arbor Railroad and main promoter of the Royal Frontenac Hotel—via private rail car to Frankfort. A civic reception was organized in Frankfort.

Following that, a unique offer was made by Kirby in his tireless efforts to promote rail use and hotel stays. If the Congregationalists agreed to have their “Congregational Summer Assembly” (CSA) on the now unused railroad land between Crystal Lake and Lake Michigan, the Ann Arbor Railroad Company would give them the land—175 acres just two miles north of Frankfort. The catch being that they must bring at least 200 non-local persons a year for the first five years and construct public and private buildings to house no less than 300 persons at a cost of at least $10,000.

The CSA utilized the Royal Frontenac Hotel for the first year, with the railroad providing promotional material and rail passes for CSA officials, as well as offices and meeting rooms at the hotel. Hotel rates were pricey, so after the first year, the Congregationalists camped on and began to develop the Crystal Lake property. In 1910, the CSA had met the railroad company’s requirements, and the deed was passed to the land the CSA still occupies to this day. (See our online archives for a complete history of the CSA from August 2018.)

Beyond the CSA microcosm, it is hard to imagine the sudden environmental, social, and economic changes that the hotel and railroad operations must have had on the community and surrounding area.

Guests were pouring into town from cities foreign to local residents, and rail freight rumbled in from all over the United States, coming and going on ships 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Passenger-package freight ships dropping off hotel patrons and their belongings could then reload local fish and produce for sale in urban markets for the return trip, thus creating an outside market for Benzie County goods. Moreover, in such a culturally homogeneous area, the influx of more than 150 students from the historically black Fisk University in Tennessee would increase diversity each spring, as these students became employed as servers, porters, and cleaning staff, in addition to locals who were also employed at the hotel.

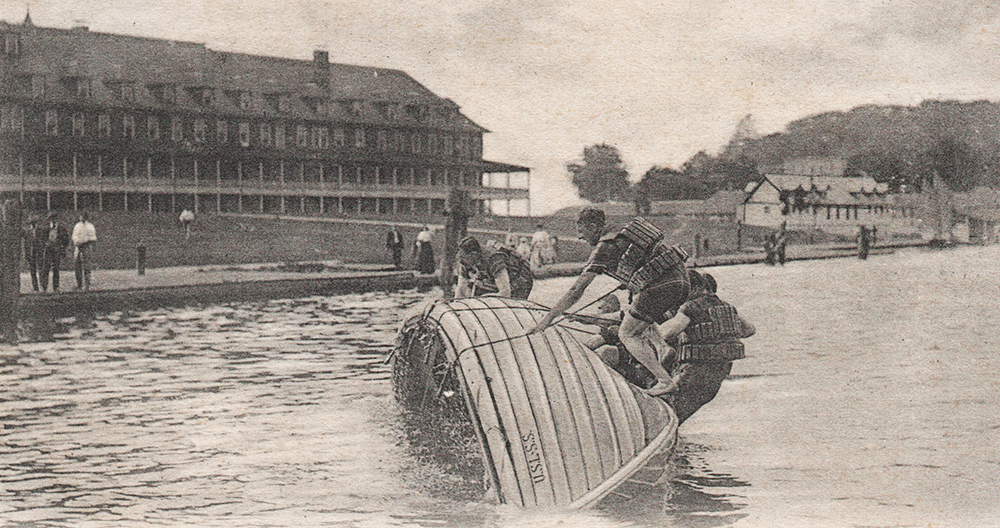

Proficiency drills conducted by the U.S. Life Saving Service stations at Elberta and Point Betsie suddenly became performances for throngs of summer spectators from the hotel or the CSA. Locals offered boat rentals, horseback riding, swimming lessons, and a nine-hole golf course where Graceland Fruit now stands. The railroad offered a “ping pong” locomotive and windowless railcar running back and forth between the hotel and Beulah three times a day. Local businessman Bill Rathbun sought to profit by placing slot machines in the hotel’s game room.

The lengths to which the railroad went to attract ridership and hotel patrons may paint a reality that stands in contrast to the romantic image of the hotel.

The first hotel manager, J.R. Hayes, had previously been in the employ of the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island. His vision of the Royal Frontenac was of serving a very well-heeled clientele, and his pricing reflected that. At the close of the second year, however, the hotel was averaging only 50 percent capacity.

So, in 1904, a new manager was hired, J.E. Davidson, and the hotel closed for the 1905 season. The hotel reopened in 1906 with a new marketing and pricing campaign. Soon, more guests, group events, and conferences booked. New to the hotel grounds was a mineral bath house promoting health and relaxation that was staffed by professionals from the Arkansas hot springs baths. The water was piped from the existing Mineral Springs Park site to the hotel facility. A bowling alley and children’s center were also erected.

In 1907, the hotel went to a shortened, seasonal operation to improve profitability; this was in place for the next four years. The hotel closed for what would end up being its final season on September 5, 1911, after one of its most financially successful seasons.

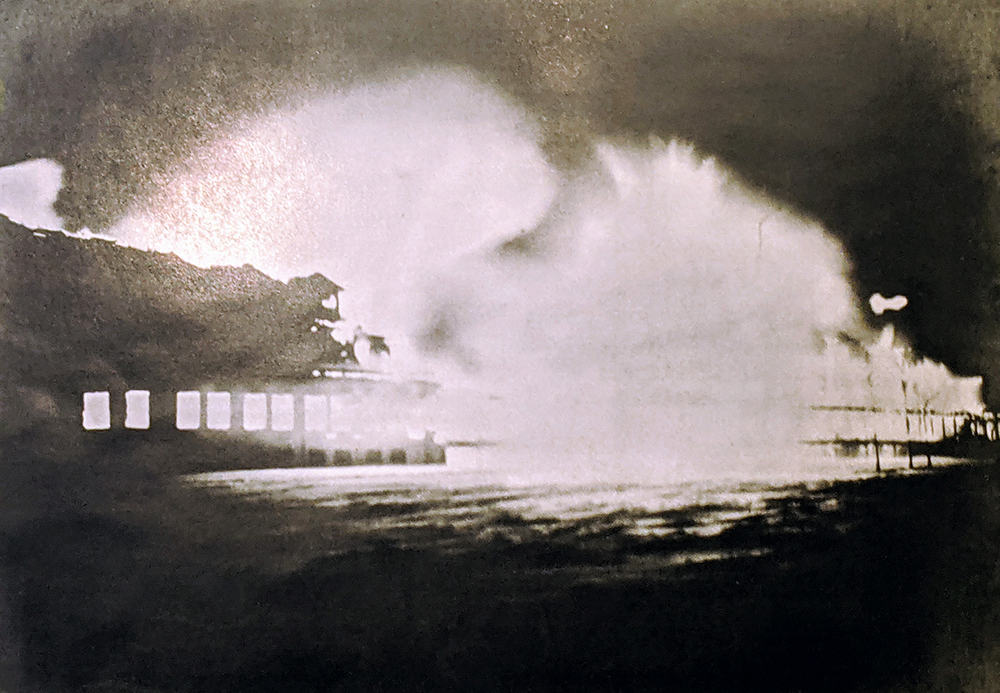

On January 12, 1912, there had been a girls high school basketball game in Frankfort, followed by a dance at the Eagles Hall in Elberta. It was a bitter cold, starry night with a light east wind; the harbor was quiet, save for the occasional distant rumbling of switch cars in the railyard. Suddenly, the fire whistle shrieked through the night, and word arrived that the Royal Frontenac—the jewel of Frankfort harbor—was ablaze.

The Fire Department sprang into action, and Chief Collier had every intention of saving the hotel. When arriving on scene however, it was apparent that little could be done, as the blaze was well advanced, even when first discovered.

Bill Rathbun arrived to the fire—along with nearly all the townsfolk—and thought of his slot machines, locked inside. Since the fire had not yet burned to the game room, given the sheer size of the hotel, he opted to run to the door and attempt entry. To his surprise, he found it unlocked, ran inside, and carried out his two machines.

Other folks saw Rathbun’s success and took it to mind that they ought to try and save something, as well; after all, everything was going to be consumed shortly in the fire. Soon men, women, and children were dashing in and out of the hotel carrying everything from mattresses and furniture to sundries from the kitchen. Even the gold crucifix was reported as “salvaged” from the fire.

Finally, the fire advanced, and entry was no longer possible. Word had it that the immense fire could be seen from the Wisconsin shore. In three hours, the Royal Frontenac was ash and rubble. Thanks to an east wind, the ancillary buildings and the town of Frankfort were spared from the flames and embers.

The following day, the Ann Arbor Railroad detective arrived in town to investigate the fire. The unlocked door cast suspicion of arson or “hobos” carelessly inhabiting the building. It could not be determined whether the fire began on one end of the structure or both, since the blaze seemed to consume the center last.

Fate by fire was a common end for the few hotels that were built of wood to the scale of the Royal Frontenac, whether it was by intent or accident. One thing clearly known to the detective was that a great deal of hotel property had escaped the fire and was not being returned. With the assistance of Benzie County Sheriff William Gates, an offer was made to area residents: return whatever you took and pay only a misdemeanor fine of $9.10. In short order, a parade of townsfolk began dragging in their loot and turning it over to authorities.

The Ann Arbor Railroad never rebuilt the resort, and the profile of the area never regained the architectural or social prominence that was once afforded by the great hotel. But for close to two decades at the turn of the last century, the small, rural city of Frankfort was the epicenter of much technological and architectural progress—the tallest building north of Grand Rapids; the novel cross-lake railroad service, which had been covered by national newspapers like The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, even attracting representatives from the British and Russian empires to see if the idea would work in their home countries; a grand 250-room hotel with the then-longest porch in the world; and even the 1904 gold medal for cherries and apples at the 1904 World Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, thanks in large part to the packing and shipping of the submissions via the Ann Arbor Railroad.

By 1950, passenger rail service had ended; in 1982, rail freight and ferry service ended. The tracks were torn up, and the ferry landing was demolished in subsequent years. Still remaining is the hotel’s mineral bath building—though without its attractive dormers—now utilized as the VFW Post on Main Street. Also still standing in testament to the era is the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, and the S.S. City of Milwaukee rail car ferry, now in Manistee, both designated National Historic Landmarks.

Of course, also remaining: the wonderful qualities of people and place that created the legacy more than a century ago.

Featured Photo Caption: For close to two decades at the turn of the last century, the small, rural city of Frankfort was the epicenter of much technological and architectural progress—a 10-story grain elevator as the tallest building north of Grand Rapids; the novel cross-lake railroad service, which had been covered by national newspapers and visited by foreign diplomats; a grand 250-room hotel with the then-longest porch in the world; and even the 1904 gold medal for cherries and apples at the 1904 World Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, thanks in large part to the packing and shipping of the submissions via the Ann Arbor Railroad. Photo courtesy of the Benzie Area Historical Society.

So very interesting to read all of the history for this beautiful area. I grew up in Benzie County in 1946 to 1964. All of this took place even before my parents were there. I did ride the car ferries with my family, when I had uncles who worked there. Thanks for sharing this great article!

This is wonderful! Frankfort and the CSA are part of my DNA, and I love learning all this history. Unless this has already been done, this whole story would make one or more wonderful documentaries for DVD sale to tourists. The vision, fortitude, and optimism of the people of that time continues to amaze me.

Great account of Frankfort’s amazing history. Congrats and thank you, Jed Jaworski, for such well-done writing. A gem of a piece. Thanks also to the Benzie Area Historical Society for those remarkable photos.

The designers of the Grand Hotel could not have designed the Royal Frontenac Hotel. The partnership was dissolved in October of 1898 according to the October 23, 1898 edition of the Detroit Free Press. A check of George D. Mason’s jobs list does not contain the hotel. Zacharias Rice may have designed the hotel, but there is no evidence.

Love the history. Made me smile and be proud of the fact that I was born and raised in that beautiful part of the world. ( Many years of course after the Royal Frontenac). Thank you for sharing this history.

I was always told that a relative of mine ran a big hotel in Frankfort. I see that the first manager of the Frontenac had my last name!

The closing lines about physical traces that remain in the cultural landscape helps visitors to walk the grounds and connect to the times long ago. Thanks for bringing the story into the present-day.