The pirate of Lake Michigan

By Richard J. Boyd

Current Contributor

In the maritime folklore of the Great Lakes, only one mariner has ever been branded a pirate. That person was Captain Daniel Seavey, who spent most of his infamous career on Lake Michigan and in its many ports. So notorious were his exploits that he became known across the region as “Roaring Dan”—a nickname well-suited to his colorful personality and pugnacious disposition.

Daniel Seavey was a large and powerfully built individual for a man of the late 19th century. He stood 6 foot 4 or 5 inches and weighed about 250 pounds. He possessed a barrel chest with long arms terminating in huge hands, all set atop a trim lower body. His hair was sandy, his complexion ruddy, and he spoke with a pronounced New England accent.

Seavey was not a Michigander by birth, coming into the world instead in Maine in 1865. His father was a schooner captain, and the son quickly took to the sea himself. By the age of 13, he was working aboard local vessels. At 18, he entered the U.S. Navy for a three-year hitch, followed by a stint as a deputy marshal for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, for which he tracked bootleggers and smugglers on reservation lands in several states.

Roaring Dan first appeared near the Great Lakes in the 1880s at the railhead at Middle Inlet, Wisconsin. While trapping in this area, he met and married 14-year-old Mary Plumley, the first of his three wives. By the 1890s, the couple and their two daughters had moved to Milwaukee, where Seavey bought a small farm and interest in several waterfront saloons.

The Milwaukee Business Directory for 1896 confirms that Seavey and a partner operated a tavern near the city’s harbor. Saloon ownership allowed Seavey to become acquainted with Frederick Pabst, the Milwaukee beer magnate. Pabst reportedly encouraged Seavey to invest in a mining company in Alaska.

Roaring Dan then pulled the first of many disappearing acts.

Without notice, he sold his Milwaukee properties, deserted his family, and left town, reappearing in the midst of the Klondike Gold Rush. He spent several years pursuing a fortune there but instead suffered a big financial loss when the company went bust.

Seavey came back to Milwaukee, but he refused to resume his family responsibilities and soon vanished onto Lake Michigan. Mary Seavey, meanwhile, returned to northern Wisconsin, remarried, and raised a large family. (She also changed her legal name to Mary Silver, an action that will be examined later.)

In 1900, Roaring Dan surfaced in Escanaba, Michigan, where he married 22-year-old Zilda Bisner—another disastrous union. Within four years, Bisner filed for divorce, her declaration describing how Seavey regularly beat her and threatened her life. When confronted with the divorce suit, Seavey once again disappeared onto the lake. Some years later, he met and wed Annie Bradley on the Garden Peninsula of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, a marriage that lasted many years.

Seavey operated various businesses in Michigan; some were legitimate and some were not. Over the years, he dabbled in marine transporting, trapping, logging, lumber milling, and even some prizefighting. On the dark side, he also practiced smuggling, poaching, bootlegging, and pimping. These activities made Roaring Dan a readily recognizable character in most lake ports, where even today many a “Seavey story” can be recounted.

One such tale emanates from the small village of Naubinway in the eastern Upper Peninsula. While working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Seavey tracked a liquor smuggler to this hamlet and cornered the outlaw in a local tavern. The smuggler boldly declared that no lawman could ever take him in hand-to-hand combat. Never shirking from a fight, Marshal Seavey launched into the violator, and the two vigorously punched away for several hours. Roaring Dan finally finished the bout by tipping a piano on the battered villain, or so the story goes. The defeated man received prompt medical attention but ultimately died of his injuries during the night. Upon leaving town the next day, Seavey telegraphed a succinct report: “Outlaw expired while resisting arrest!”

Roaring Dan was a notorious barroom brawler. At Manistee, a resident tough had beaten all local fighters and put out the word that he was seeking new challengers. Seavey quickly rose to the bait and headed to the town, where he confronted the ruffian in a saloon. A battle then ensued. Seavey flattened the Manistee upstart and hastily departed the scene, before the authorities could arrive to assess the significant property damage.

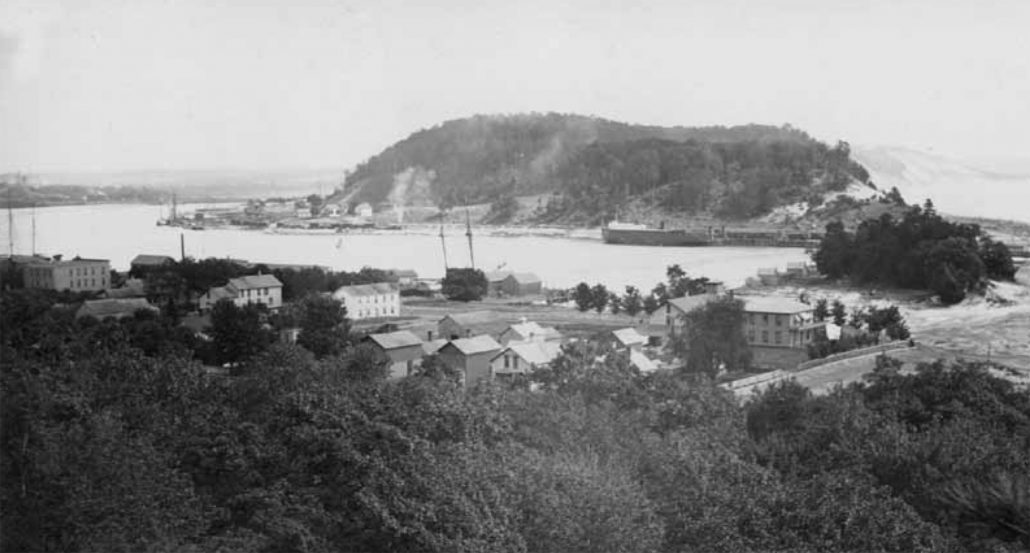

The captain occasionally fought for money. His most famous prizefight occurred in Frankfort during the winter of 1904. With considerable fanfare, Seavey battled Mitch Love, a respected pugilist from downstate. The fight was held on the ice of the frozen harbor, where a shoveled circle served as a makeshift ring. Reportedly witnessing the contest were about 200 people, many placing sizable bets on the outcome.

The contestants went at it eagerly with bare knuckles for nearly two hours. Seavey eventually made a bloody pulp of Love, who was carted off for medical attention by his dejected supporters. Roaring Dan apparently cleaned up on the contest, not only collecting the main purse but also a percentage on numerous side bets placed by his cohorts.

Often carrying a handgun, Seavey was known to be a crack shot with pistol, rifle, or shotgun. While living in Frankfort, he set up an illegal fish trap offshore at the harbor’s mouth. This was a natural attraction for other violators who wished to poach from the poacher. Roaring Dan solved this problem by running a trip line from the trap to a bell in his fishing shack on shore. Anytime the bell would ring, Seavey would fire a well-placed rifle shot into the water near the interloper, thereby discouraging further thievery.

Confidence games were another of Seavey’s many talents. During this era, a significant horse-racing enterprise had developed in Chicago. Some horse owners were convinced that their thoroughbreds exhibited enhanced stamina when fed a type of marsh hay supposedly grown only in Delta County in the Upper Peninsula. To satisfy the demand, Roaring Dan supplied boatloads of hay to Chicago racetracks—profiting handsomely from the trade. It is thought that Seavey himself sold the horsemen on the merits of this exotic feed.

Roaring Dan also made considerable cash by running a floating bordello.

Brothels were known to flourish in port towns. Local lawmen tried to curtail these unsavory activities but met with limited success, because their authority ended at the water’s edge. Using this loophole in the law, some schooner masters would load their vessels with prostitutes and liquor and travel from port to port—especially on weekends and paydays.

The Wanderer—Seavey’s 42-foot, two-masted schooner—was engaged in this activity, with Roaring Dan making the rounds of such communities as Fayette, Nahma, Garden, and Escanaba. (Seavey shared this story during interviews with noted Great Lakes historian Henry Barkhausen in the mid-1940s.)

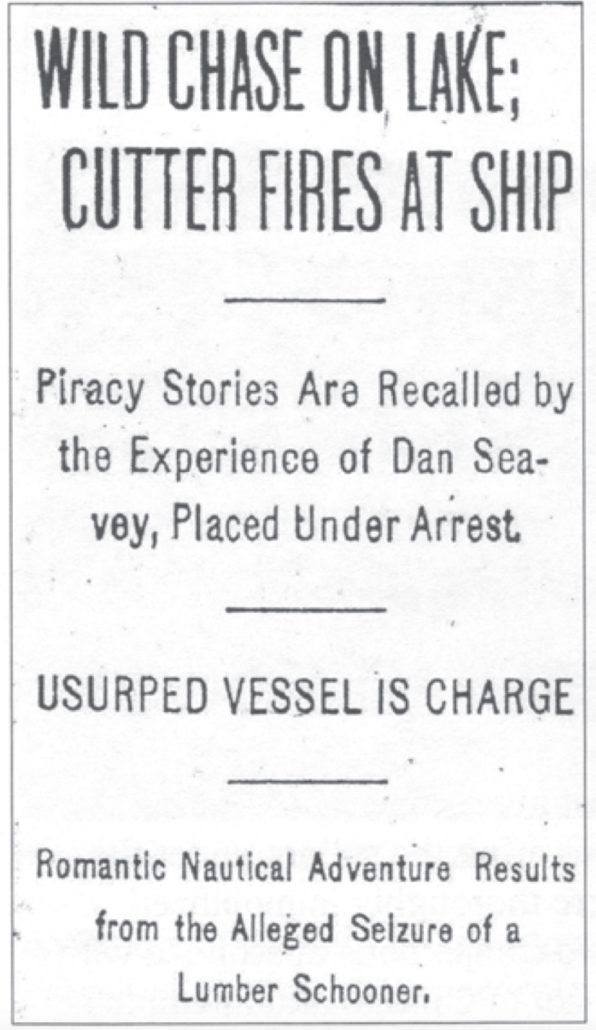

Seavey became forever famous when he was arrested for piracy, as chronicled in lakeshore newspapers. These accounts relate how, on June 11, 1908, Roaring Dan and two henchmen stole a small schooner in Grand Haven, thereby initiating a nautical cat-and-mouse game with federal authorities.

It was suggested that Seavey approached Captain R.J. McCormick, owner and master of the Nellie Johnson, and several crew members in a local saloon. After some socializing, Seavey enticed the group into more serious drinking until they became immobilized. He then absconded with the schooner and headed to Chicago, intent on selling the ship’s cargo of cedar posts.

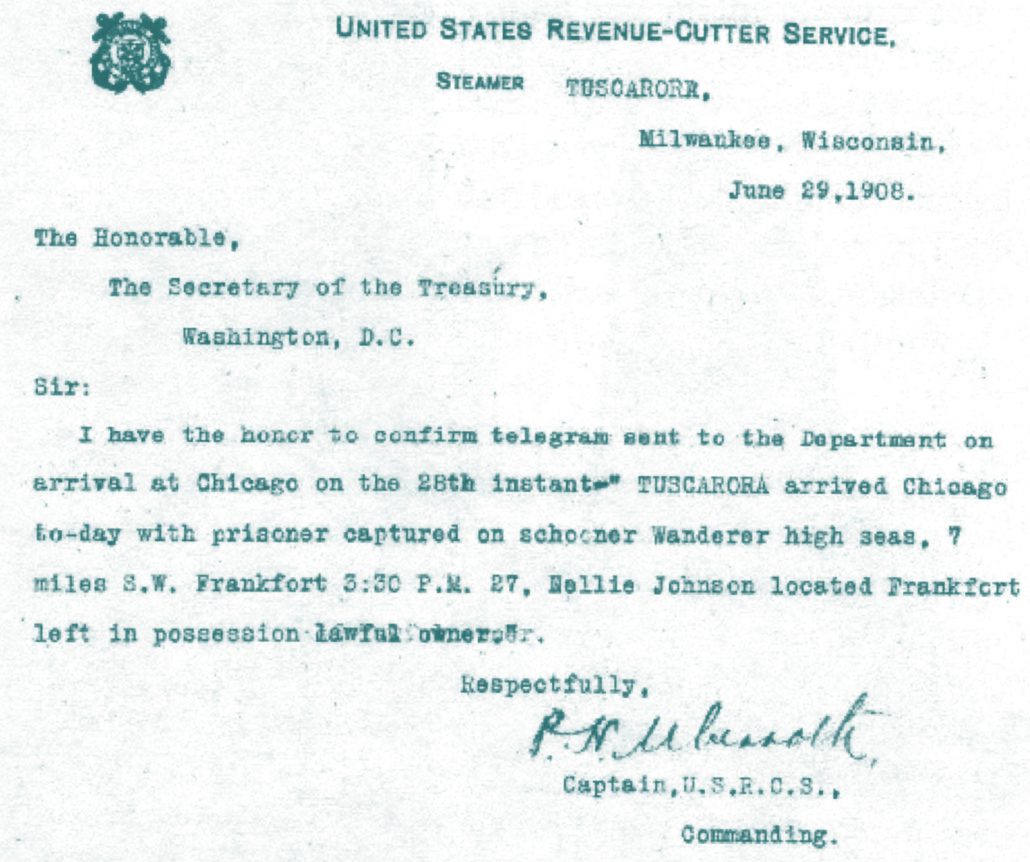

Surprisingly, Seavey and his crew could not unload the posts on Chicago’s thriving black market, so they headed back across the lake and up its eastern shore. By then, McCormick had hastened to alert government authorities of the theft. On June 20, nine days later, the federal revenue cutter Tuscarora steamed out of the Windy City in pursuit of Roaring Dan, with Captain Preston Uberroth in command. Aboard were McCormick and U.S. Deputy Marshal Tom Currier with an arrest warrant for Seavey.

The charge, it was said, was piracy.

The Tuscarora—a 178-foot, steel-hulled gunboat that was reputedly the fastest ship on the Great Lakes—cruised up the eastern shore, stopping in every port and obscure backwater where Seavey might be hiding.

This routine proved slow and fruitless, so—at Ludington—Captain Uberroth telephoned all the lighthouses and lifesaving stations to the north and asked their crews to search for the pirate. Eventually, the lifesavers in Frankfort reported that Seavey was there, having hidden the Nellie Johnson on a nearby river.

The cutter headed north, pausing in Manistee in late afternoon. Uberroth decided to refuel there and proceed to Frankfort under the cover of night, fearful that Roaring Dan might be warned of their approach by his many friends in the area. The gunboat arrived in Frankfort about dawn and sailed on to anchor north of the city, below Point Betsie. In mid-afternoon, the schooner Wanderer was spotted sprinting out of the harbor under full sail, headed across the lake. The Tuscarora weighed anchor and gave chase at full speed, reportedly burning the paint off her smokestack and boilers. Seavey was said to have paid no attention to signals to drop his sails, which prompted the gunboat to end the chase with a well-placed cannon shot along the schooner’s waterline.

A team of armed lawmen then boarded the Wanderer and arrested Roaring Dan, who was placed in irons for the trip back to Chicago.

On June 30, just 19 days after the initial heist, Seavey was arraigned, not for piracy, but for mutiny and sedition on the high seas. Despite the government’s best efforts, however, a grand jury failed to indict Roaring Dan on the charges, and he was set free. The chase and the case against the alleged lake pirate received extensive newspaper coverage all across the country.

How did Roaring Dan escape imprisonment, when clearly he had stolen the Nellie Johnson?

No one really knows, but speculation abounds. Some say that Seavey’s lawyer, an old hunting buddy, was well-connected in Chicago’s legal community and that strings were pulled to ensure the captain’s release. Others suggest that Roaring Dan had been a seaman on the schooner and was owed money by Captain McCormick; this theory has some credibility, given the mutiny charge, which suggested some formal relationship with the vessel. Still others have postulated that Seavey was acting in his capacity as a federal marshal in some arcane manner.

Whatever truly happened, Roaring Dan was forever after branded a pirate.

Research into this event in Seavey’s life poses a challenge. Officials at the National Archives have concluded that no hearing transcriptions survived and that no grand jury records were archived. Similarly, the arrest warrant no longer exists, so its exact language remains unknown.

However, in the official logbook of the Tuscarora, the pursuit and arrest of Roaring Dan are clearly described. First, the log discloses that the gunboat did not burn the paint off her stack during the chase of Seavey; that occurred several days earlier, while the ship steamed north at flank speed. And the cannon shot never happened. In the official record, the Wanderer hove to as the Tuscarora approached. Seavey stepped aboard when requested, and was summarily arrested by Marshal Currier; no contingent of armed men was involved. Roaring Dan was then placed in the brig and taken to Chicago without incident.

What can one conclude from these discrepancies?

Clearly, the newspapers enhanced elements of the event—as was the “yellow journalism” practice of the time. Certainly the cannon-shot scenario did not occur, because it would have been recorded in the official log. It was likely fabricated by the Chicago Daily News, which followed the event closely and first reported it.

Moreover, the media may have introduced the idea of piracy. None of the official documents examined actually cites this charge. On the other hand, the now-lost arrest warrant could have listed piracy, but that charge might have been amended at the time of arraignment—a fairly common procedure. Thus, the precise origin of this claim remains unclear.

Roaring Dan was 43 years old when his arrest occurred. Throughout the rest of his life, he publicly decried the affair, proclaiming his innocence and denying all accusations of piracy. In the 1940s, when interviewed by Henry Barkhausen, Seavey declined to recount the details, but referred to all officials involved as “liars.”

Despite his public protests, however, there is evidence that Roaring Dan viewed things quite differently in private.

In 1923, Seavey and a business partner purchased a tract of land at Gouley’s Harbor on the Garden Peninsula to establish a sportsmen’s club. The club never materialized, and today that property is a land conservancy. During a review of title transactions for acreage, a fascinating quit-claim deed was found. The document stated that Mary Silver waived all dower rights to the property being purchased by John Silver, also known as Dan Seavey. Readers will recall that Seavey’s first wife changed her name to Mary Silver after they parted ways. However, this deed discloses that they were never legally divorced, and they may have rekindled their relationship under the guise of John and Mary Silver.

The alias of “John Silver” recalls the fictional pirate Long John Silver in Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic book, Treasure Island. The choice of this name may suggest that, in his private life, Roaring Dan wore his piracy label as a personal badge of honor.

While still in Gouley’s Harbor, Seavey suffered a burn injury in a suspicious sawmill fire that claimed the lives of two men. (The exact details of this event in Roaring Dan’s life are nearly as difficult to pin down as those surrounding the stolen schooner of 1908.) Due to the injury’s lingering effects, the captain retired from sailing in his 60s and took up residence at Martha Champ Weed’s boarding house near the Escanaba waterfront. In the latter part of the 1930s and into the ’40s, he lived quietly with his daughter Josephine in several communities near the border between Michigan and Wisconsin.

He died in a nursing home in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, in 1949, and was buried at Forest Home Cemetery in nearby Marinette.

In his later years, Seavey was known to be quite religious and was often seen carrying a bible—a stark contrast to his earlier life and the legends that surround “the pirate of Lake Michigan.”

This article is a reprint of “Roaring Dan Seavey: The Pirate of Lake Michigan,” which was published in Michigan History, a magazine produced by the Historical Society of Michigan, Vol. 96 No. 3, May/June 2012. hsmichigan.org. Used by permission.

Dr. Richard J. Boyd is a director of the Wisconsin Underwater Archeology Association and author of the book, A Pirate Roams Lake Michigan: The Dan Seavey Story, which can be found at the Benzonia Public Library and the Benzie Shores District Library in Frankfort.

Featured Photo Caption: A portrait of Dan Seavy: known as a turn-of-the-century Great Lakes mariner to some, pirate to others. Photo courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

It so happens that my grandpa was possibly one of the two that fought with Dan Seavey in the fight on the ice in Frankfort, Michigan. My grandpa’s name was Edward Ward, and at the end of the fight, I’m not sure if it was actually with Dan Seavy or one of his crew, however, at the end of the fight my grandpa had won said fight and was offered by Dan Seavey his daughter Josephine’s hand in marriage.

My grandpa Edward Ward chose not to marry Miss Josephine, Dan Seavy’s daughter, and thank Mr Seavy for the offer, however, several years later he married my grandma Rose and they had seven children together and resided in Elberta, Michigan.

My cell phone # is 386-855-0401

My name is Marva Anderson.