The “Green Man” of Benzie County

By Carol Navarro

Current Contributor

Editor’s Note: Typically, this publication is not in the habit of printing obituaries, just as we do not have a classified section or op-ed contributors, nor do we highlight the outcomes of local elections or athletic events. These are simply not the kind of things that we run, given that there is already a newspaper in town doing just that. Rather, our pages are filled with what we consider to be (mostly) uplifting feature stories about the interesting people, places, and events of Benzie County.

However, we have recently—for the second time in our nine-year history—had to ask ourselves what our publication would do in practice when the certainties of life occur. Many of our readers are surprised to hear that we had two years of publication back in 2005 and 2006; we profiled Rick Jones in 2005. On Saturday, May 16, 2020, 69-year-old Jones—husband, son, brother, uncle, friend, Vietnam veteran, Purple Heart medal recipient, anti-war advocate, motorcyclist, musician, artist, poet, storyteller—left this world.

Although running obituaries is not common place for The Betsie Current, we, the editors, believe that there is value in sharing about this great man, a community treasure, and we thought that you would, too—whether you are reading this for the first time ever or just for the first time in 15 years. What follows is a semi-updated version.

——————-

“When the mountains were young, and the trees were old, and the world had but just one soul…”

These words ring out from the earthy baritone of the man who is jokingly referred to as the “the Mayor of Bendon” by his fellow musicians from Song of the Lakes: Ingemar and Lisa Johansson and Michael Sullivan. (For the record, there is no mayor of Bendon.)

Rick Jones—the gray-bearded man with twinkling eyes in a multi-colored robe and cowboy boots—looks more like a wizard than a self-proclaimed local politician. He picks up one of his percussion instruments and cradles it in the palm of his hand. Slowly scraping it with a cow’s rib, he engages in a dialogue with a cello. These organic rhythms progress into a bluesy energy of song. Suddenly, the audience finds itself transported to the middle of a Benzie County swamp, eavesdropping on a conversation between unseen creatures.

Some would argue that what is so amazing is not what the audience hears, but what they cannot see: the stick-like instrument that he holds.

A closer look reveals that the instrument is a deer antler, transformed into the shape of a ‘swamp lizard,’ scales and all. The Tennessee-born Vietnam veteran, musician, and storyteller—who describes himself as “just an old hippie”—is also a self-taught master carver and sculptor.

“Rick Jones is the most brutally honest man I know, and the most untamed in the best sense of the word,” says Crispin Campbell, one of Jones’ musician friends. “It’s this spirit that connects him to the natural world.”

Campbell recalls a story that Jones once told him about sitting very still for a long time in a hunting blind, when a young deer approached him, and after checking him out, came closer and gently licked his face.

“This could only happen to Rick Jones,” Campbell says.

Nature and mythology are Jones’ muses. From his perspective, his own work cannot compete with Mother Nature.

“You just get information from her and love her,” Jones says. “You can’t improve on the Mother. If you try, she’ll kick your ass every time.”

Jones credits his father’s influence for his fearlessness when venturing into the art world.

“Dad can do anything he wants to do. He had to. There was no one else to do it. I have that same kind of spirit,” Jones says. “I’ve been doing this stuff all my life, but in 1974, after I got back from Vietnam, I got serious. I love museums. I knew I would never be able to afford what I saw in museums and art galleries, so I decided to start doing my own stuff. That way, I could have a house filled with art.”

Mike Sullivan, a bandmate in Song of the Lakes, has known Jones for close to 40 years. He remembers Jones’ father.

“He was a junk man. So I think Rick learned to see beauty in what other people consider rubbish,” says Sullivan, who recalls a time when a historian/artifact collector was showing Jones some of his pieces of scrimshaw and other carvings. The historian pulled out a very old carving. It was Jones who immediately saw the second image, opposite of the main image, which the owner had never noticed in all the years that he had it.

Although Sullivan claims hanging out with Jones has almost gotten him arrested a couple of times, he has great respect for his “pagan-Baptist” friend’s art.

“He’s a genius in terms of a sense of reality,” Sullivan says. “He can create that reality in his visual art. And it’s in the eyes of his creations that capture it.”

Those who know Jones describe his art as connected with the natural world. The spirit he gives to his creations embodies the many realms of nature.

A tour of his home and studio quickly reveals this—every corner and shelf is inhabited by his creations. An absence of formal schooling has not discouraged Jones from following his own instincts. As a teen growing up in Lansing, he started spending hours in the library, even though he says that he could “barely read.”

“I used to walk up and down the library aisles with my arms spread out and let my fingers brush the books,” he says. Today, his home is filled with art books. Pulling a Rodin book off the shelf, he will tell you that “I look at this stuff, and I can see what he was doing.”

In the 1970s, after his return from traumatizing experiences in Vietnam, Jones made his living from carving scrimshaw: scrollwork, engravings, and carvings that are done in bone or ivory. He grabs an object from a shelf. It is a tooth from a sperm whale with a detailed scene of a shipwreck etched into it.

“I’d stop in a truck stop and sell my stuff to the waitresses,” he laughs. “I’d make $500 at breakfast.”

Then fate dealt its hand during his travels—Jones was heading to Montana from Lansing, when his truck broke down in Honor in Benzie County. While waiting for repairs, he met a man who saw some of his sculptures in the back of his truck. He accepted the man’s offer of six months rent in a cottage that he owned in exchange for one of Jones’ sculptures.

“So here I am,” Jones says, gesturing to his backyard of forest and swamp—his playground and material source for much of his work.

For his sculptures, it’s “lots of clay.”

“What I like about working with clay is the instant gratification,” Jones explains. “You can ball it back up and use it again if you make a mistake. You can change horses in midstream. You’re only limited by your mind. But eventually, the clay starts dictating what it wants to be—you can have a preconceived idea, but form takes a life of its own, and your idea means nothing.”

He points to an example, his “Manitou Mermaid.” Her voluptuous body, long hair, and tail are draped in a fluid position around an armchair with half-closed eyes, creating an alluring expression. She sits on a desk in front of his favorite lounging spot.

“Carving is not as forgiving. You can’t send it back,” says Jones, adding that his carving materials choose him: bone, antler, wood, or stone.

He holds up a work in progress.

“This set of moose antlers has been filed to help smooth out the grizzly bear teeth marks,” Jones says. Then, laughing in his bellowing tone, he adds, “He ate the ends, like two big cookies.”

The antlers are testimony to Jones’ ability to see form in natural objects. In another finished carving, an eagle’s head has been sculpted as if the outer layer of the moose antler was simply peeled back to reveal its white crown. The eyes, beak, and tongue are so lifelike that one expects the bird to swoop down and pull a fish from the water.

Jones holds up another moose antler. Leafy etchings branch out across the blade from the center, where a set of piercing eyes seem to possess a watchful awareness. His expression sharpens, and his voice becomes noticeably pensive as he talks about this piece.

“This is the Green Man,” he says. The detailed tattoo on his right arm bears out the reverent fondness that Jones feels for this icon. “There is an image of him in every primitive culture. He is the protector of the forest.”

Jones explains that the Green Man’s face appears not only in indigenous cultures throughout place and time, but in the art and architecture of many churches and universities of the Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance periods. His image appears again and again, from Iceland to Scotland; from the cathedral of St. Dimitri in Russia to the famous Chartres Cathedral in France to Santa Maria Del Mar in Spain.

His description of the Green Man leads him to share one of his own mythologies: with the crucifixion of Christ, Jones believes, a veil was dropped over the eyes of man. The ability to see the elemental kingdom disappeared. This, says Jones, is proven over and over by the killing of the indigenous cultures who celebrate the earth and the pervasive devastation of forests and many other life forms on this planet.

“We continue to destroy around the world,” he says, “Like a plague of grasshoppers that eat everything in sight.”

Ask Jones to describe his art, and he will say that he does not fit into any one category.

“Well, my closest guess is I’m ‘folk art,’ but I really don’t have a clue,” he says. “There is a forced naivety with folk art [that] I don’t like. I’m more romantic.”

Romantic seems to be the right word for Jones and his art, if romantic means passionate vitality.

“I’ve created a lot of ‘elemental’ pieces by breaking off tree branches while hiking in the woods,” Jones says. “The running sap from an injury forms an image. I’ll see a face, an animal, anything. I get real excited, and if I’m with someone, I’ll ask them if they see it, too. Usually, they don’t,”

He shakes his head.

“I can’t understand that.”

The vitality is in the eyes of his creations, whether his mermaid, eagle, or Green Man. Their watchful surveillance supports his philosophy.

“Art is about creating the illusion of something that isn’t there,” Jones says.

And it is the eyes of his creations that make you look over your shoulder as you leave the room; just to make sure.

“…with creatures that fly and critters that crawl. In the meadow, this is what we saw…”

Full disclosure: Carol Navarro is married to Crispin Campbell, quoted in this article.

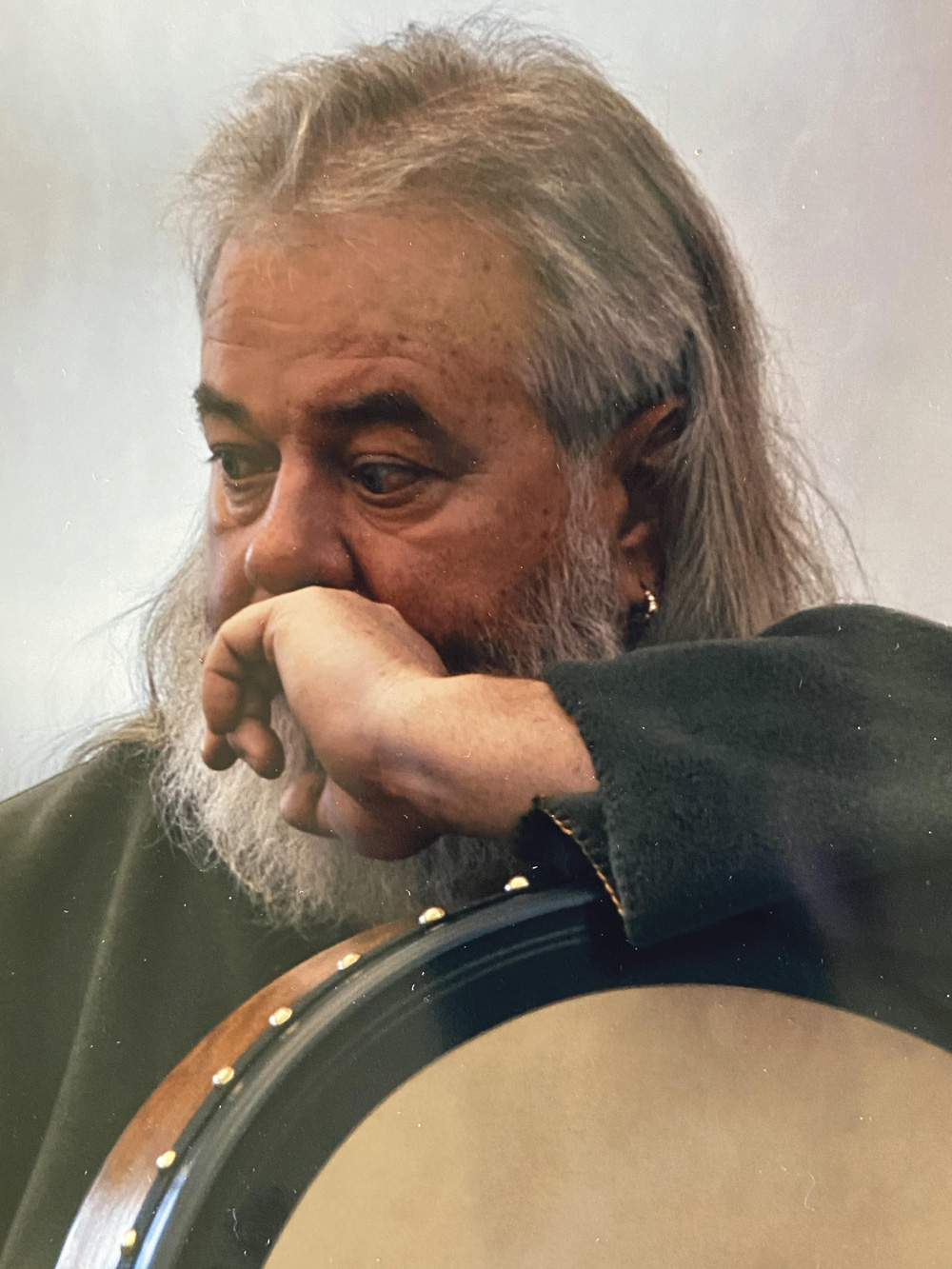

Featured Photo Caption: Posing with a drum, Rick Jones—husband, son, brother, uncle, friend, Vietnam veteran, Purple Heart medal recipient, anti-war advocate, motorcyclist, musician, artist, poet, and storyteller. Photo by Carol Navarro.

Great article describing this man and his art contribution.

I was a friend of Carol’s and visited your house a ccouple of times. She showed me your work and we talked about the magic down the hill behind your house. I was seeing Linda Callahan also and though we only knew each other a short time I missed her a lot when she was gone.I think that she is the one who took me to the hills over by Lake michigan to look for Dutchmen’s Britches. I had never seen such big ones. I used to drive to Benzonia to do Acupuncture with Dr. Wagber. I had to leave TC many years ago but it is memories like these that keep me coming back. She was one special lady.

Once upon a time many years ago I was hiking through a dense, thick cedar swamp somewhere in Benzie County. I was antler shed hunting in the early spring just after the winter snows had melted away. I thought I had the place to myself when I encountered another hiker. It was Rick Jones, we shared the days finds, one shed each. We swapped stories and talked a little art. Rick was truly a one of a kind. I feel blessed to have known such a kind and talented person. TWF

Really great article, Carol. Well written.

Wonderful article. I possess 2 of Rick’s sculptures. One we bought from him direct and the 2nd we bought from him at the MSU summer art show. We have enjoyed them for over 40 years.