Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund brings essential service to Benzie and beyond

By Emily Cook

Current Contributor

The arrival of March means many things. Winter’s intensity lessens, the sun shares its light for more hours of the day—accompanied by the sounds of returning robins and red-winged blackbirds from their southern migration—and outdoor enthusiasts swap their cross-country skis for hiking boots and mountain bikes once again.

Without fail, March also brings “baby season” for Michigan wildlife. From a clutch full of chickadees to a family of opossums to a sleeping fawn, the young creatures of the region are plentiful in spring. Unfortunately, this can result in a higher likelihood of stumbling upon an orphaned or injured animal—how should someone living in Northwest Michigan handle this situation?

Samantha Wolfe (32)—originally from Benzie County, but now residing in Grand Traverse County—has an answer.

“Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund was started to help rehabilitate and restore the wildlife and the wild spaces that exist in the northwest lower [peninsula of] Michigan, and to help connect people to nature through wildlife,” she says.

Slated to begin operation this spring—just in time for the aforementioned “baby season”—Wolfe and SBWF’s co-founder, Justin Grubb (31), a wildlife photographer and biologist, will be providing a much-needed environmental service to the region. (Grubb’s wife’s family is from Northern Michigan.)

Apart from raptor-specific facilities—North Sky Raptor Sanctuary of Interlochen and Skegemog Raptor Center on the east side of Traverse City—other rehabilitation nonprofit organizations are currently two or more hours away, based in Grand Rapids, Eaton Rapids, and Houghton Lake.

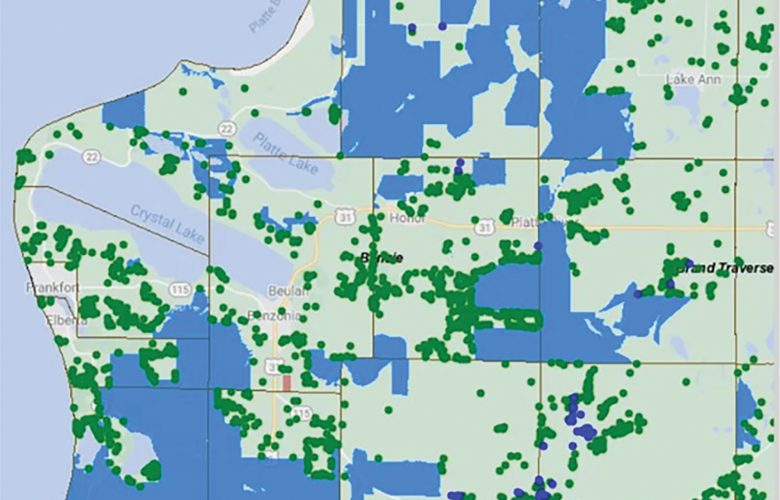

“Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund is based in Benzie County and covers northwest lower Michigan—wildlife populations don’t care about municipal boundaries and county lines,” Wolfe says. “As long as we are able to arrange transport, I am happy to be a resource for the wildlife in [the greater] area.”

SBWF will start out by helping to rehabilitate opossums, rabbits, and squirrels at the Benzie location, but the organization will also be able to take in myriad other animals temporarily, until they can be transferred to another rehab facility. Regardless if the animal stays with SBWF in Benzie County or is moved to another appropriate organization, the hope is to be able to release these animals back to the wild, once they are healthy and viable.

Pathfinding

The trajectory of Wolfe’s life is varied, but ultimately, it is not surprising that her path led to this point.

“I grew up here, so I took these spaces for granted. But as soon as I started college, I knew that protecting the environment would be my calling,” Wolfe says. “It’s been more than a decade, and I’ve taken a winding career journey to realize this mission, but I am thrilled to be on the precipice of something great with Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund.”

Growing up in Benzie County, she learned much from her grandfather, who she considered “the original naturalist.” He was an early role model for her regarding land stewardship—teaching her about beech-maple forests, foraging, and gardening.

“After college, I spent several years in New Jersey in environmental education and outreach roles,” says Wolfe, who graduated from Benzie Central High School in 2009 and from Kalamazoo College in 2013 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in environmental studies; she later received a Master of Arts degree in biology in 2022 from Miami University, where she met Justin Grubb. “I attended many of the classes that I scheduled [in New Jersey], so I learned a lot from experts in the field at that time, too. That was when I began volunteering at a wildlife rehabilitation center, and I also did amphibian-migration monitoring, bird-banding, and horseshoe crab rescue on the Delaware Bay shore.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Wolfe realized that she needed to return home to Northern Michigan. Soon after her arrival back, she discovered the environmental education and wildlife resources that she had come to know and appreciate through professional experiences were essentially nonexistent in her hometown.

“I had a lightbulb moment that this could very well be my calling—and now, three years later, it’s a reality,” Wolfe says.

The last three years have been busy with a multitude of steps being taken to prepare for becoming an operational wildlife rehabilitator. In order to prepare for wildlife patients, supplies are being collected, facilities developed, and Wolfe has been making significant efforts to develop her knowledge and further her education.

For now, the facility location will not be open to the public, to ensure that the animals being treated receive privacy and are kept safe. Wolfe and volunteers will soon work together to find public locations to pick up injured wildlife from people who have found them.

“I have a few seasons of hands-on rehabilitation experience with both birds and mammals, and I have a wonderful network across several states. I’ve been reaching out to other organizations’ founders and directors to learn how they started and how they scaled, and I have learned so much already,” Wolfe says.

She is a member of the International Wildlife Rehabilitation Council (IWRC), National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association (NWRA), and the Ohio Wildlife Rehabilitators Association—the latter of which because Michigan does not currently have a state network. She has also been volunteering with North Sky Raptor Sanctuary and attending online conferences over the past three years. Additionally, she just returned from Delaware, where she attended her first in-person NWRA conference.

“I’m still working full-time in my conservation ‘day-job’,” Wolfe explains. “Many people refer to wildlife rehabilitation as their unpaid profession—right alongside their paid one—and I’m sure I’ll start introducing myself this way soon. In many cases, wildlife rehabilitation doesn’t pay; this is why we started the nonprofit, and the long-term goal is to fundraise enough to have a public-facing space with additional revenue streams, like programming, grants, etc.”

The Animals

It is clear that Wolfe is well-prepared for the possible influx of aid that may be needed this spring and beyond. At first, the Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund will focus on opossums, rabbits, and squirrels. However, they will welcome all calls about injured and orphaned wildlife. They will also be able to take in birds on a case-by-case basis, as Wolfe is a sub-permittee for migrating birds via North Sky Raptor Sanctuary.

The goal is simple for the organization:

“Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund is here to provide a resource for wildlife in our region, whether we are the ones delivering the treatment or we are leveraging connections with other facilities to make sure the animal is receiving the best care possible,” Wolfe says. “In some cases, we might just be a safe place for a patient to await transfer to a more experienced facility, but the great part is that we will have the resources they need and will be a legal, permitted option right here in northwest lower Michigan.”

Unfortunately—but also realistically—not every species of animal can be accepted or responded to.

In Michigan, you are not legally allowed to rehabilitate bats, bears, adult deer, or skunks, for instance. Raccoons and fawns are allowed but may come later for SBWF, so that the organization is able to scale and grow appropriately—both of those animals come with additional concerns, such as roundworm or rabies in racoons and chronic wasting disease in deer.

Wolfe adds:

“We also won’t have the capacity to take many birds for the next year or so, because baby birds eat every hour from dawn until dusk, and we’ll need more volunteers and hopefully staff before we are able to commit to that quantity of care. That said, one of our goals is to help connect people who find wildlife in need with appropriate resources—even if it’s not us.”

While the Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund will be a fantastic regional resource, it is also important to remember that not all “orphaned” animals require care.

In many cases, the baby animal is okay. Fawns, for example, are often left alone for quite some time in order to keep them safe, while the mother ventures off. Additionally, if a baby bird has fallen from a nest, in many cases, they can be safely returned—unlike what urban myth will tell you, most birds do not have a well-developed sense of smell (this excludes species like vultures), and nestlings can be tucked back in as a warm and safe space from predators. (In other words: No, the mother bird will not be able to “smell” you and thus will not “kick” her baby out of or abandon the nest because of your scent.)

If you do have to rescue a baby animal, always make sure that gloves are worn and hands are thoroughly washed to keep both you and the animal safe from diseases.

Wolfe makes another excellent point:

“One of the most common reasons people call about wildlife is that their dog or cat has gotten into a nest or attacked a baby animal. Rehabilitators will ask that you please secure your pets and keep children away, and—if a baby animal is uninjured—let the animal’s parents continue to raise them. They do a much better job than humans ever could! If they are injured, of course, we need to step in.”

The Future

Sam Wolfe, Justin Grubb, and the nonprofit’s board members have big goals for the future, with a lot of groundwork being laid for what the future of the Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund may look like.

Following the exciting realization that they had met all of their 2021 and 2022 goals, additional long-term dreams include a facility with paid staff and interns, research, unique wildlife-based educational opportunities, and more.

Looking at 2023, however, they are ready to respond to your wildlife-rehabilitation needs for small animals, as well as being a resource for other questions.

Visit SleepingBearWildlife.org online or “Sleeping Bear Wildlife” on Facebook or @wildliferehab.nmi on Instagram to learn more about how to volunteer or just for general information. Contact SBWF directly via phone at 231-590-8639 or email hello@sleepingbearwildlife.org. Donations are also very welcome, as they serve as the foundation to keeping these resources available in Benzie County.

Emily Cook is a resident of Arcadia, where she lives with her husband and their two collies. She is a conservationist by training and a writer and artist when the time allows. She explores the nearby nature trails and Lake Michigan beach as much as possible.

Featured Photo Caption: Samantha Wolfe (32, left) and Justin Grubb (31, right) are co-founders of Sleeping Bear Wildlife Fund, a new nonprofit to help rehabilitate and restore the wildlife and wild spaces that exist in the northwest lower peninsula of Michigan that is slated to begin operating this spring. Photo courtesy of SBWF.