Views on legendary Jim Harrison

Jim Harrison lived for 35 years near Lake Leelanau before he moved to Livingston, Montana, and wintered in Arizona. Known for books like Legends of the Fall and Revenge, Harrison’s best-selling novellas, novels and poetry about the wilds and wild characters of Northern Michigan represented our region to worldwide audiences. He was big in France. His words also spoke to Americans who had never set foot in the forests and trout streams of the mitten state. (My friend Tim, an Italian-American kid from Brooklyn, already had a perception of this region before he visited for the first time to attend my wedding in 2008. The Northern Michigan he knew was shaped by Harrison’s novels, which sit on his bookshelf in Chicago alongside those of New York Jewish writers Chaim Potok and Philip Roth.)

Because this setting appears prominently in his work, Harrison was often falsely compared to Ernest Hemingway. In fact, as writers and writing teachers know, Hemingway’s hallmark was writing short, simple sentences. (“The old man cursed the fish.”) Whereas Harrison’s prose and imagery were a tour down a winding dirt road—by the end of the journey, the reader coughed from the dust and wept at the loneliness that Harrison had evoked.

Jim Harrison passed away on March 26, 2016, at the age of 78. Two days after his passing, our sister publication, the Glen Arbor Sun, reached out to the following local writers who had known the famed author. We asked how Harrison had affected them personally, as well as how he affected Northern Michigan writing, in general.

Michael Delp, writer, poet, former creative writing teacher at Interlochen Arts Academy, Boardman River bard

Jim was a force unto himself, deeply cosmic and just as deeply earthly. He could stand with one foot in the river and the other on another planet and be perfectly comfortable navigating the distances between, then weave those various locations and celestial associations into virtually any form of the three genres he inhabited so elegantly. He was beyond a lion, and, in fact, was an entirely different species, though he would surely say in no uncertain terms that he preferred the bird’s life to anything else. I came by his work in the late ’60s, picked it up, thought he was speaking directly to me, and I never stopped treating his writing as sacred text. I used it, and still do, almost as a daily devotional of a sort. Every day, I remind myself that “we are more than dying flies in a shit house, though we are that, too.” I taught his work for 40 years in all kinds of classrooms, and my students held him to their wild hearts, using his words as soul food to fuel their own hormonal flights into what they were told was enemy territory. Jim taught them the exact opposite. I suspect that more than one writer is working through the humus of how they relate to Jim’s work, and what it means to them now that he has left for the stars. As for me, I know he is mixed up in my DNA: he worked on me at a biological, molecular, even an atomic level. It would be necessary to send more than blood samples to some exotic underground lab for me to find out, knowing full well that there is literally some brain tissue where he set up camp and never left. If writers have a sense of audience—beyond their loved ones and their progeny—Jim was mine. I often thought of him while I worked, and he surely has had a marked effect on who and what I am as a writer. That is not to say I wanted to emulate him, for no one can do that with any writer. But, I praise his ability to see so clearly, so honestly, and so consistently.

This winter, I engaged in a full-out writing assault on Facebook, offering up what I call “deck sentences” (a reason for the names escapes me now), and Jim was certainly the target of them, as well as a select few people I long for in my heart. This one is for Jim:

Early morning deck sentence: For Jim

Either everything counts or nothing does, no middle ground these days, yet I navigate the dark, tangled river between these two countries, never knowing which side to set up camp, build a fire, and find enough words in the coals to continue on… tonight, a clear, dark sky, the entire constellation of Sagittarius flared and then disappeared, vanished, and I thought I heard the giant hooves of God’s horse either approaching or riding away, wondered what the difference was between them, wanting more than ever for it to be on His way toward me, readying myself prepared to be scooped up and carried in those warm saddlebags, Jim’s voice steadying the ride.

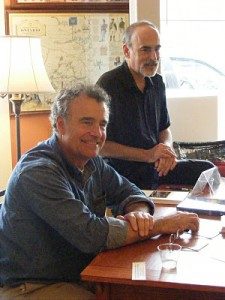

Jerry Dennis, author

Jim and I were acquaintances. We chatted when we ran into each other, but our only lengthy conversation was two hours over the phone for an interview we did for Traverse Magazine in 2014. We never fished or hunted or drank together. But that didn’t matter to me. What I had was his work. Off and on for 35 years, he has been my favorite author. “Off and on” because periodically I grew disenchanted. With the teenaged butts, for instance. With the thousand-dollar lunches. Ten years ago, my buddy Dan Donarski and I were drinking Budweiser around a campfire and worked ourselves into a froth over the food porn. It was a betrayal to people like us, who could never afford a sliver of truffle, let alone a hunk the size of an apple. We swore we were done with him. Then a week later, I read The Summer He Didn’t Die, and, oh shit, the guy’s a genius. And I started devouring every word again.

Jim and I were acquaintances. We chatted when we ran into each other, but our only lengthy conversation was two hours over the phone for an interview we did for Traverse Magazine in 2014. We never fished or hunted or drank together. But that didn’t matter to me. What I had was his work. Off and on for 35 years, he has been my favorite author. “Off and on” because periodically I grew disenchanted. With the teenaged butts, for instance. With the thousand-dollar lunches. Ten years ago, my buddy Dan Donarski and I were drinking Budweiser around a campfire and worked ourselves into a froth over the food porn. It was a betrayal to people like us, who could never afford a sliver of truffle, let alone a hunk the size of an apple. We swore we were done with him. Then a week later, I read The Summer He Didn’t Die, and, oh shit, the guy’s a genius. And I started devouring every word again.

What I return to over and over is the poetry. Every time a new collection appeared, I read it straight through two or three times, then kept diving in, again and again. One winter, I read all the poems in sequence, from the first collection to the latest. It was an amazing experience. I recommend it. From youth to old age, the honesty is there, as are the rawness, the artlessness, the absolute assurance, the voice stripped of affectation. You won’t find any tricks, no showing off, no efforts to impress or be coy, clever, or “literary.” The poems are nothing but pure soul, I think.

And, yes, thoughts of death seemed never far from his mind. Keep it in our own minds, he said, and we’ll remember to pay attention, to live big, to embrace the world and one another, to not waste ourselves on trifles. That might be his greatest gift to us.

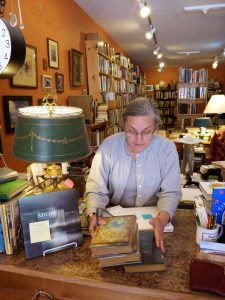

P.J. Grath, bookseller at Dog Ears Books in Northport

I didn’t know Jim Harrison in Hollywood meetings or Paris lunches of many hours and many courses. I knew Jim and Linda at home, in their old farmhouse down the road from Lake Leelanau, with their daughters and their friends, their dogs and cats and gardens, and, long ago, Linda’s horse, later, her pet rescued crow. Also, memorably, at the Bluebird in Leland.

I didn’t know Jim Harrison in Hollywood meetings or Paris lunches of many hours and many courses. I knew Jim and Linda at home, in their old farmhouse down the road from Lake Leelanau, with their daughters and their friends, their dogs and cats and gardens, and, long ago, Linda’s horse, later, her pet rescued crow. Also, memorably, at the Bluebird in Leland.

When we first met, the Harrisons were driving a car missing one of the back windows, the glass replaced by cardboard held in with duct tape, a car that exemplified the phrase “winter beater,” though they drove it in all seasons. This was before Hollywood money allowed the remodeling of the old house. Even then, Jim told me proudly that he always kept plenty of good food in the refrigerator and pantry. He might skimp on other things but never on food. Years later, when a number of friends were assembled in the house for a dinner party during sweetcorn season, Jim gave the signal to a handful of us to run out and pick the corn only when the water in the pot had reached a full, rolling boil.

Was that the same year that younger daughter Anna was feeling somewhat under the weather and requested duck broth? Linda observed with a wry smile that the family food obsessions had “created a monster.” (Not so. Like her mother, choosing a lightly traveled road, Anna married a poet.) And was that also the same time—somehow they blend together in memory, mental snapshots from different years and seasons all jumbled—that I hauled my Correcting Selectric III from Kalamazoo to Lake Leelanau to type a sheaf of new poems for a book Jim was putting together?

It’s true that Jim Harrison lived a big life. What is missing in all of the public obituaries, though, for me—and I realize the public at large might not care so much—are the workman, the husband, and the father. I remember older daughter Jamie’s high school graduation party, with tables set out all over the front yard at the farmhouse. (Jamie also became a writer.) And I can see Jim, standing at the kitchen counter in the morning, barefoot, wearing shorts and a loose, untied bathrobe. There is a cat stalking the counter, and Jim is having his first cup of coffee and cigarette of the day while discussing the cat and the day’s menu for lunch with Linda. Soon he will get dressed and go out to the granary, his office, to spend hours at work, undisturbed.

The year I took the typewriter to his house to type the poems, we walked out to the granary together. It felt strange, accompanying the poet to his usually solitary hermitage. Besides, there were the poems.

“I feel as if I’ve been reading your diary,” I told him.

“You have been,” he said.

And then we worked. No goofing around. When Jim worked, he worked. Two new books out just this year, Dead Man’s Float (poems) and The Ancient Minstrel (novellas).

We heard on NPR that Harrison told an interviewer once he was sick of irony in modern literature and that he would rather take the risk of being thought “corny” for exploring the full range of human sentiment than “dying a smartass.” He could be a smartass at times, in social situations, but his writing came always from the heart, undisguised. And he got his work done.

Bless you, Jimmy! Our world was larger because you were in it and is smaller now without you and Linda.

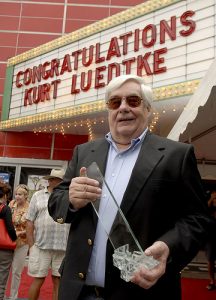

Kurt Luedtke, Academy Award winner for Out of Africa screenplay; former Detroit Free Press editor

I don’t think I knew Jim well. I was coming into the movie business at about the time he was leaving it, so we crossed paths and knew some of the same people. My memory is that he was often kind to me, including me in things. Giving me credit for knowing things I didn’t know.

I read almost all Jim’s stuff and thought his prose was better than his screenplays and his poetry remarkable. Jim and Hollywood were a fair fight; who won I suppose depends on how you think about these things.

An unusual number of the people who reviewed his novels seemed to think that men who wrote and walked in the woods must be critically located somewhere in a Hemingway genre, which I thought was not very careful thinking. I thought Jim’s sensibilities were delicate, often feminine. Whatever that means.

Jim and I and some other people were in the bar in the Townsend Hotel, down the street from our house in Birmingham. Jim was on a book tour, which he hated, and the rest of us were there to put him to bed. There was a woman, quiet, not with us, and her husband, overstuffed and ignorant. At some point, the woman slipped away, perhaps to the ladies room—but she didn’t return. I hardly noticed. Much later, Jim told me that it was her disappearance which gave rise to his Dalva, which some think his best novel.

Back in the day, some writers incorporated themselves so they could fund their own self-directed, tax-deferred pension plans. I did. Jim did. I put my pension money in bonds. Jim bought the quite large, quite expensive wine cellar of a Lansing-area dentist which might have appreciated some more if it had aged a while longer. In later years, Jim would say he was still working because he’d consumed his pension.

Jim must’ve had lots of stories but he didn’t tell them around me, maybe not anybody. I thought, ‘Maybe he’d rather write them than tell them.’ Around me, he was more a commentator than a storyteller, full of apercus, some cryptic, some elaborate. He had an enormous working vocabulary and a huge store of adjectives and adverbs. At one time, the word of choice was “swinish.” It was interesting to see how a mind like that can so effortlessly use “swinish” in ordinary conversation.

It’s said that Jim was at his desk, working out a poem, when he died. I hope that’s true.

Ray Nargis, longtime Michigan writer, Beach Bard, currently lives in Calistoga, California

Like many, I first heard of Jim Harrison long before I read anything by him. In the fall of 1973, I interviewed Allen Ginsberg and his longtime lover, Peter Orlovsky, for CM Life, the student newspaper at Central Michigan University. Ginsberg was there for a reading, and we spent a rainy afternoon at the home of my fine poetry teacher, Eric Torgersen, smoking weed and chatting.

Like many, I first heard of Jim Harrison long before I read anything by him. In the fall of 1973, I interviewed Allen Ginsberg and his longtime lover, Peter Orlovsky, for CM Life, the student newspaper at Central Michigan University. Ginsberg was there for a reading, and we spent a rainy afternoon at the home of my fine poetry teacher, Eric Torgersen, smoking weed and chatting.

I wanted to know about Kerouac, Snyder, and the rest of The Beats, but Ginsberg started talking about some new Michigan writers he’d heard about or met. One was Tom McGuane and the other some bricklayer/poet named Harrison. McGuane, I’d heard, had written some stoner Opus Magnus about Key West called Ninety-Two In The Shade and was moving to Montana. Harrison was from Reed City and had produced three collections of poetry, most famously Letters To Yesenin that had just come out and was, according to Ginsberg, “brilliant.”

By the summer of 1975, I’d moved to the hippy section (Vine Street) in Kalamazoo and was buying cocaine from a guy on Portage Lake whose sobriquet was “Fox” and turned out to be Tim Allen. I was also starting to write poetry and hanging out with local musicians: Terry Thorne, Stu Mitchell, and Penny Williams. We all loved “The Writer’s Series” in the library at Kalamazoo College, which John Woods and Conrad Hilberry had helped start, and that fall, I got to hear McGuane read from his screenplay, Rancho Deluxe.

He also waxed ecstatic about his buddy: of Jim Harrison’s forthcoming novel, called Farmer, McGuane said that it would “eclipse anything any Michigan writer had ever produced.”

Flash forward to the fall of ’75, and I’m on a walkabout in Suttons Bay, sitting in Boone’s Prime Time Pub, considering moving north. By then, I’d seen a picture of Jim Harrison in some newspaper article, read some of his work, and knew he lived in the area.

And in he walked. Rubber boots, bird hunting Carhartt jacket, massive head and torso winnowing down to almost dainty legs. He stank of wet dog, gun bluing, and cigarettes; swept the room with a wild-eyed reptilian gaze (I didn’t know he was blind in one eye); and, like a raptor, satisfied that his territory held no usurpers, ordered two fingers of Seagram’s VO. I expected a deeply resonant, basso profundo explosion of a voice, but what came out was a highly pitched, mountain-lion-baby scream from just below his Fu Manchu mustache. As if Truman Capote had gargled with barbed wire. He looked like a Mexican bandito that someone had recently fished out of a murky lake. ‘This,’ I remember thinking, ‘should be interesting.’

Anne-Marie Oomen, author, poet, former chair of the creative writing department at Interlochen Arts Academy

In the early ’80s, he sat across the bar at Boone’s in Suttons Bay and occasionally made lewd remarks to the waitress, and when I asked who he was, my shock could not have been greater—that’s Jim Harrison? I promptly began eavesdropping.

In the early ’80s, he sat across the bar at Boone’s in Suttons Bay and occasionally made lewd remarks to the waitress, and when I asked who he was, my shock could not have been greater—that’s Jim Harrison? I promptly began eavesdropping.

He fascinated me with conversation just loud enough that I knew for sure he wasn’t a reckless drunk—though he did drink. And it would be easy to call him the proverbial bad boy, but he was more than that—you could tell by the vocabulary and the clarity. After that first encounter, I went home and read Farmer, the quietest and, in some ways, truest of his novels.

After that, we ran into each other in the way of Leelanau County folk, at bars (particularly Dick’s Pour House and the Bluebird) and literary events. We met each other formally at the Hemingway conference, where one evening he spoke on the Milliken stage with John Voelker, who published under the name Robert Traver (Anatomy of a Murder). His sloppy apparel contrasted with Travor’s dapper dress, but it was one of the smartest on-stage conversations I have been present to, ever, though he repeatedly grabbed his left shirt pocket for cigarettes that were no longer welcome on stage.

Though I remained ambivalent about his novels, I discovered his poetry. I knew this poet had a stunning sense of idea and rich understanding of the internal landscape as a wild reflection of the natural world.

In the ’90s, my husband and I purchased, with several friends, a plot of land on Peanut Lake in the Upper Peninsula, and on weekends we hung out at the Dunes Saloon, where he came in on Sunday nights to use the pay phone and sit at a table. He made a place for David and me at that table. There, after the long walks with his dogs in the woods, he held court—no other way to say it. At first, I had hoped to have a conversation with Jim; I didn’t understand that one had a listen with Jim and counted it excellent, and I learned to feel grateful for it. Though he welcomed us and was kind and generous, he was clearly the one leading the talk—no matter who else was at the table, and there were some names there. I realized I could not have kept up with that amazing mind anyway, that I had little to offer to the breadth of that intellect, and that I should shut up, sip my wine, and take in whatever I could. I did.

He taught me there are some people who are bigger than this world, who make their way anyway. My place was to read his poetry and to think about poems, and that is what I have attempted. Poorly perhaps, but consistently. I could never match his poet’s bigness, but I am grateful for his iconic presence, his literary shadow that brushed over us. I bow to it in this time of his going, which it is said he did while writing a poem.

Doug Stanton, best-selling author, founder of National Writers Series

Since I was 14 years old, I had been aware of his writing, his presence. I hadn’t spoken to him in a while. Today, I’ve had a number of moments where I’ve taken a walk and remembered the funny and entertaining things that we did with Jim when I started my career as a writer. Driving his Land Rover from Lake Leelanau to Patagonia, when he knew I was broke and employed me as his driver. He had just completed the screenplay Wolf. It had been approved; we went to dinner, and he was really thrilled.

Since I was 14 years old, I had been aware of his writing, his presence. I hadn’t spoken to him in a while. Today, I’ve had a number of moments where I’ve taken a walk and remembered the funny and entertaining things that we did with Jim when I started my career as a writer. Driving his Land Rover from Lake Leelanau to Patagonia, when he knew I was broke and employed me as his driver. He had just completed the screenplay Wolf. It had been approved; we went to dinner, and he was really thrilled.

My reaction to his passing is that, for a lot of people, he provided a unifying theory which is to be authentic and true to one’s self. And to be creative. It’s why he was so charismatic. People sensed that about him. I remember going at 4:15 one day to Dick’s Pour House with Nick Reens and Jim. I kind of realized in retrospect that it was another forum of tutelage… This guy was so smart and fascinating. I realized, ‘I’m going to learn how to be in the world by being in a world alongside him, even if it just means having a beer alongside the shuffleboard table at Dick’s.’ Conversations with him were symphonic. We’d be talking about a South American bird, a Russian poet, and the Batman movie starring his friend Jack Nicholson. It was thrilling to try to keep up! I didn’t often succeed.

Jim was this almost contradictory person in that he was very public but also very private. I remember we were together at [Paris Review founding editor] George Plimpton’s apartment in New York. There was the sunken office, famous for a Truman Capote scene. I had gotten a job at Esquire, because Jim had come to my and Anne’s wedding in Northport and given me the name of an editor there. I went to New York and got hired, and then traveled around the world. I ended up in some real interesting places.

He was always helping people in one way or another. He had a great deal of empathy for people from all walks of life. He was able to talk with almost everyone. He was the first writer I ever met. He and my father went to grade school together in Reed City… To meet Jim was a powerful experience. Traverse City was not the place then that it is today. I would see him at Horizon Books. They would front him free books when he couldn’t foot the bill. When he left, there was an energy that left the room.

The National Writers Series was created to continue to have really fascinating experiences with writers. But also to do for others what he did for me when I started out. That’s why we bring these visiting writers into local classrooms… His spirit and generosity truly inspired what I’ve tried to do on a volunteer basis with writers and writing. Still, I’m feeling confused. I’m very sad at his passing.

For a long time—aside from a few people at Interlochen, Kathleen Stocking, and the Beach Bards network—Jim was the only member of the writers club up here. He had a style that you could fool yourself into thinking you could imitate. But it would never really work. Because Jim wrote so naturally that it seemed effortless. In some ways it was. I went to the cabin in the U.P. to visit and interview him. He’d write in longhand on a legal tablet, and he made it seem to be an enjoyable activity. At the end of which you’d get to treat yourself by going to the Dune Saloon [in Grand Marais] and having a drink. He wrote all the time.

He became a high-water mark in our area for dedication to one’s craft and also to a certain kind of range.

He was almost philosophical and sensitive. The French really liked him because he was like a philosopher and man of action. He also had a great B.S. monitor. I’m thinking of his memoir called Off to the Side. He was that third pronoun, keeping others honest. And when it came to political debate, he was never afraid to speak his mind. I’ve never met someone who was so sarcastic but at the same time had such a big smile on his face.

Kathleen Stocking, author

The thing that people love about writers is not them—since all of them are flawed and some of them are ridiculous—it’s their ability to see into the mystery of existence. Writers are the shamans of our time.

The thing that people love about writers is not them—since all of them are flawed and some of them are ridiculous—it’s their ability to see into the mystery of existence. Writers are the shamans of our time.

That’s what I loved about Jim Harrison. His poetry, his willingness to be eaten by a bear or drown in a river while fishing, to risk everything to get at the essence of what it felt like to be out in the woods, to be human—that’s what made him and his writing unlike anyone else’s. Yes, Thoreau and Whitman wrote about nature, but they were city boys compared to Jim. He was all backwoods. His sense of the earth’s joy and sorrow are unexcelled. Only Harrison could have written:

Amid pale green milkweed, wild clover,

a rotted deer,

curled shaglike,

after a winter so cold

the trees split open.

I think she couldn’t keep up with

the others (they had no place

to go) and her food,

frozen grass and twigs,

wouldn’t carry her weight.

Now, from bony sockets,

she stares out on this

cruel luxuriance.

Back in the 1960s, my mother had Jim Harrison and Gary Snyder come speak to her students. She was the diva of the English Department at the Traverse City High School. I asked her, “What was Jim Harrison like?” She answered, “Trying very hard to be normal.” Jim was not normal. He was a wilderness savant. Snyder, for all his having grown up in a lumber camp on the West Coast, was more civilized.

My first venture into journalism was an interview with Jim Harrison. When I told him that I had never interviewed anyone before, he observed dryly, “So I’m your guinea pig.” He was poor then, fending off bill collectors on the phone as we talked. He could have been a university professor and a writer, but he had too much integrity and so was starving and contemplating suicide instead. Luckily, he had just won a Guggenheim. His tiny daughter Anna breezed past, ignoring her father, insouciant in the way only children can be. He loved that. He imitated her little brush-off wave of her little hand.

He was funny. He showed me a poster of Chief Joseph on the wall of his back shed. He showed me a dead wasp he had taped there and said, “To give it hidden meaning.” He was serious, too. He explained, by quoting James Joyce, how he was able to write. Joyce, who had a schizophrenic daughter, had said, “She falls. I dive.” Harrison was a diver, and he dove deeper than anyone around. He also showed me the bare buttocks of a calendar girl and shared that he fantasized doing her from behind. Of course he loved his wife; saying loutish things was his way of keeping women at a distance. It worked.

I didn’t see Harrison again until my family moved to Lake Leelanau, and he would sometimes come by to visit my husband. I was fat and dumpy by this time, living in squalor. One day he came, unannounced, the living room filled with boxes I’d set up for my rambunctious three-year-old to crawl through while I worked a pint of ice cream, busily knitting my own enormous flesh burka around my too-small bones. We lived in the same community, but—other than those few visits he made to talk to my husband—I never saw him.

fsnow

By this time, Harrison was famous and rich, having written several successful novels and screenplays. He was one of the few writers out there who had the courage to work the seams of America’s creepy history of extermination of the Indians, destruction of the land. His way of seeing—with himself and people small in the context of something much larger and more unknowable—was powerful.

“What if I own more paperclips than I’ll ever use in this lifetime,” he writes in Letters To Yesenin. “My other possessions are shabby: the house half painted, the car without a muffler, one dog with bad eyes and the other a horny moron. Even the baby has a rash on her neck, but then we don’t own humans.”

Out in the community, people would drop his name, especially the wealthy tourists, the ones who called him “Jimmy” and imagined that they hung out with him at the Bluebird, the ones you knew had probably never read his books or spoken to him, since no one called him Jimmy. A lot of people wanted to say they knew him. It seemed fatuous to me, but then I realized it was their way of paying tribute.

Harrison was the real thing, the genuine article, a writer, the living link to the terrifying places no one wants to see, and people wanted to claim proximity. Of course, he misfired sometimes. That’s the nature of the work. But that he could do it at all and, in his case, do it well, was sufficient proof of his incredible gifts. He will be missed.

Norm Wheeler, manager of the Beach Bards bonfire in Glen Arbor, co-editor of the Glen Arbor Sun, recently retired English teacher at The Leelanau School

Anna Harrison graduated from Leelanau School in 1989 after two years with us, and Jim Harrison delivered the graduation speech one sunny Memorial weekend. It was the first time I saw him in a suit. He said, “Your school motto says ‘Straight as the Pine, Sturdy as the Oak’. That kinda limits your mobility, doesn’t it?”

Anna Harrison graduated from Leelanau School in 1989 after two years with us, and Jim Harrison delivered the graduation speech one sunny Memorial weekend. It was the first time I saw him in a suit. He said, “Your school motto says ‘Straight as the Pine, Sturdy as the Oak’. That kinda limits your mobility, doesn’t it?”

Jim always had the right words. I got to know him during those two years, because he’d visit my class to read some new poems or I’d see his car down at Art’s Tavern in Glen Arbor and stop to get a beer and eat popcorn, slathered in hot sauce, with Jim and Nick Reens. We also went to Grand Marais those summers, and he’d come into the Dune Saloon for a nightcap. He’d walk back into the kitchen, then come out and smack two balls of raw hamburger meat on the bar for his dogs waiting out in the Range Rover, sit next to me, and order up a VO. And talk. It was the most interesting talk I ever heard, full of philosophical meanderings, stories from the West Michigan childhood we shared (he was from Reed City, I was from Shelby), brilliant improvisations on the writers he loved (Lorca, Matthiessen, Yesenin, Machado), delicious and salacious bad-boy wisecracks about T & A, and tales of monumental meals.

Jim’s talk wandered through all of the profound themes and perfect quips that his writing does. His voice and cadence were as unique and unforgettable as the words that came out of his mouth. Forever after, whenever I am reading Jim’s poems, fiction, memoirs or essays, I hear his voice like he’s talking to me, the same reedy lilt, the same laughter and lingering over his favorite words: “banaaal”, for example, or “schooshers” (for ski enthusiasts). He talked about a lot of the things that ended up in his books later: the time he met Orson Wells for dinner in New York and, after several courses and several bottles of prime wine, had to head for the men’s room to put his finger down his throat so that he could continue; the way Mattheissen returned from his The Snow Leopard trek in Tibet still walking on air when Jim met him in New York; or careening at top speed through the Everglades, armed and loaded with Jimmy Buffet. So when I read Jim, I swear I hear his voice, because it’s like he told me this before, like he was saying it out loud before he wrote it down.

My wife, Mimi, and I had a couple of unforgettable meals with Linda and Jim at their place near Lake Leelanau. Linda was the sweetest, kindest person ever. I joined Doug and Anne Stanton at Anna’s wedding in Livingston, officiated by Zen priest Peter Matthiessen, and I also met Peter Fonda, Tom McGuane, Tim Cahill, and Doug Peacock. I couldn’t believe I was partying at the Murray Hotel surrounded by these guys! And the last time I saw Linda and Jim, we visited their place in Patagonia with Suzanne Wilson. He was always fun, brilliant, irreverent, off the wall, and all heart. He was generous. When Mimi was in Denmark for a few months around the time of her mother’s death, Jim was the only friend who offered to help us financially if we needed it. We didn’t, but I will never forget his care and concern.

Jim was never fooled by the fame that came with Legends of the Fall and his success with some of the screen plays. He said that, when he was broke and went out partying around Leland, he was labeled an alcoholic. But after he hit it big in Hollywood, people just called him “a problem drinker.” And then he’d crack out that knowing Jim snicker and squint at you, the one good eye twinkling. You never forget the times you spend with a certified genius. I got to hang with Jim Harrison.

Read the Glen Arbor Sun’s August 1997 interview with Jim Harrison: http://glenarborsun.com/qa-interview-with-jim-harrison-august-15-1997/