Gold fever attracts media frenzy

With all the talk lately of shipwrecks and sunken treasures off the Benzie County coastline, locals couldn’t help but notice when a fleet of officially marked state vehicles, police, and media descended upon the Frankfort boat launch ramp on the morning of June 9. The visitors boarded four boats—including both a State Police and a Coast Guard vessel—then, under the cover of thick fog, disappeared offshore.

“Could this have something to do with the recent frenzy over gold treasures?” onlookers wondered from shore.

People love a good story, and a tale of lost gold treasure, shipwrecks, and two unlikely heroes determined against all odds to find the hidden bounty resonates with many. Based on a 40-year-old deathbed confession about a treasure that sank off Frankfort in the 1890s, treasure hunters Kevin Dykstra and Frederick Monroe have traversed more than 1,200 miles in their modest family boat, searching off the Frankfort coast to locate a treasure that they believe lies just offshore.

The treasure is thought to be $2 million dollars worth of Confederate gold, concealed in a boxcar that sank into the depths of Lake Michigan after being cast off the deck of a storm-tossed ferry. One could imagine such a tale while waiting in line at the Frankfort post office if they stared at the stunning mural of Car Ferry #4 jettisoning box cars in a 1924 storm. The legend also includes a second tale about a safe, full of jewels, aboard a “sunken boat with a cabin.”

Historical research attempts to substantiate the claims, however, are clouded by a series of extremely unlikely coincidental twists and turns over the past century.

“We believe this treasure is out there,” Dykstra says. “Or we certainly would not have put this much effort into it.”

From the Big Screen to International News

To date, historians have found little validation to the pair’s claims, which read like the script from Richard Brauer’s film Lost Treasure of Sawtooth Island starring Ernest Borgnine that was shot in Frankfort in 1999.

Though Dykstra and Monroe have yet to find the gold, they have made other discoveries during their search that have garnered attention. Ross Richardson—the diver with MichiganMysteries.com who discovered the area’s infamous rumored treasure ship Westmoreland—says, “When you sonar search that much lake bottomland, you’re bound to find something.”

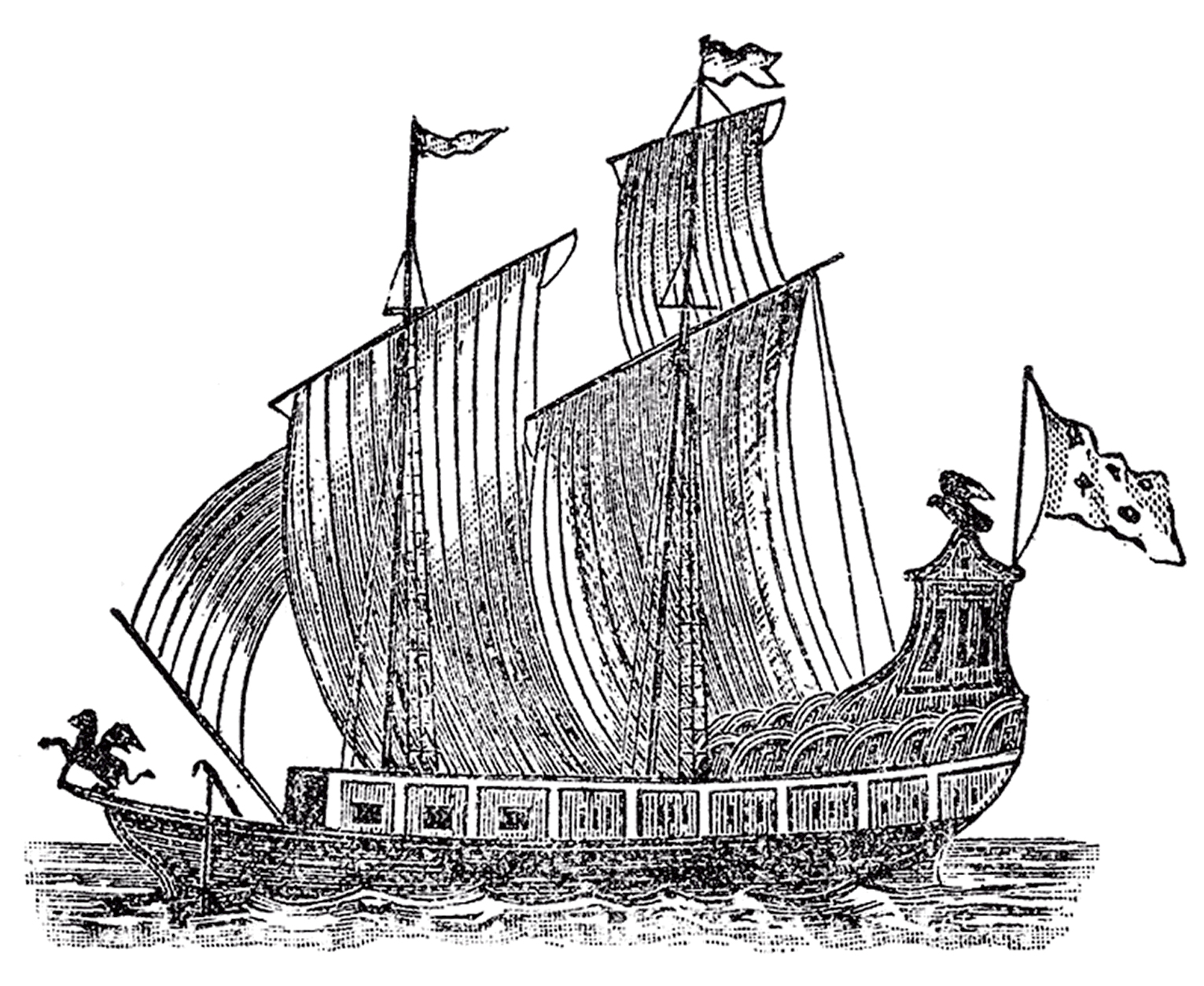

Dykstra and Monroe released a statement last year indicating that, three years ago, they had accidentally found what they believe was LaSalle’s 1679 sailing vessel Griffon, the first European vessel to sail Lake Michigan and the holy grail of Great Lakes shipwrecks. When they found the wreck, the pair have said, they saw what looked like drawings they had seen of the figurehead on the Griffon, so they reported it to the State of Michigan. (The two have also said that they are not really focused on the Griffon, but rather they want to find the gold.)

These statements garnered an exclusive news scoop by WZZM TV near their hometown of Muskegon and have since generated a frenzy of attention by Great Lakes historians and the media.

WZZM announced more recently that the pair found an undiscovered sunken tug, possibly owned by a prominent jeweler, with an unopened safe that matches the description of one supposed to contain gold and jewels. The report spread like wildfire and exaggerated its way from the next day’s edition of USA Today and The New York Daily News to the Daily Mail in London within less than 24 hours.

Dykstra and Monroe again reported the discovery to the state, indicating they will abide by Michigan law and not disturb the wreck site or open the safe. They released shaky video snippets of the two wrecks, but the clips did little to support their claims. Nevertheless, media outlets shared them broadly as “see it with your own eyes” footage.

Truth and Skepticism

Experienced divers and maritime historians, on the other hand, determined from the video footage that the alleged Griffon was likely a small wooden steamboat. The “treasure tug” was swiftly identified as the small steam freighter Jane, which sunk carrying 500 bags of concrete in 1927 to the south of Frankfort. Jane was discovered in the 1990s and documented in “as found” condition by a collaboration between a civilian diver and the State of Michigan.

A video was posted to YouTube that showed the newly discovered Jane wreck and discussed the preservation dilemmas associated with new shipwreck finds.

What Dykstra and Monroe claim to be the ship’s safe is clearly visible in the video’s footage and is actually a square cook stove sitting in the galley.

Valerie VanHeest, of the Shipwreck Research Association in Holland, shared the frustration of many historians and underwater archeologists.

“I fear sensationalizing can minimize the significance of real discoveries and important history,” VanHeest says. “Not every shipwreck is going to have gold treasure or a mysterious safe aboard it. We work hard to preserve a lot of amazing, true history on the lake bottom, not fantasy.”

The Jane preservation video was viewed fewer than 100 times prior to Dykstra and Monroe’s find. Within 24 hours of their treasure safe claim, however, it was being viewed around the globe.

Skeptics of the pair’s intentions postulate that they may just be hyping their way to a reality TV contract. It is difficult to accept that Dykstra and Monroe, who are smart enough to coordinate a GPS-integrated sonar search, can’t conclude that the vessel they are calling a tug has no tow bits or that the wreck claimed to be the Griffon is twice the Griffon’s size and 200 years newer. Additionally, the treasure hunters have not integrated with the larger maritime-preservation community to assist in researching or investigating sites before making public claims or involving state investigators.

Gold Fever

Back at the Frankfort launch ramp on June 9, the flotilla has returned, and aboard is state archeologist Wayne Lusardie. His mission was to investigate Dykstra and Monroe’s claim of finding the Griffon.

“It is most definitely not the Griffon,” Lusardie says. “The discovered vessel appears to be a tug that burned to the deck. We already know the suggested safe aboard the Jane is the vessel’s cook stove from examining archived video footage of the wreck.”

When asked if he is concerned about such casual claims of undiscovered shipwrecks and treasure, Lusardie answers, “This is my 17th Griffon claim investigation. I am happy people are interested enough in our maritime history to bring our attention to something like this.”

Perhaps it is simply “gold fever” that has convinced Dykstra and Monroe that a previously discovered steamer wreck full of concrete is an undiscovered treasure tug and that the ship’s cook stove is a jewel-filled safe. The two unassuming men seem to make friends easily wherever they go. The pair has been very cooperative and upfront with the City of Frankfort, according to city superintendent Josh Mills.

“I don’t see how this can be a bad thing for Frankfort,” Mills says. “They are paying their own way, it’s drawing a lot of attention to our area, piquing people’s interests, and sharing some of our real history. I hope this inspires us as a community to reengage with our maritime history. Kevin and Frederick have even helped us to organize, train, and fund our Fire Department Dive Rescue Team.”

It seems that everyone is benefiting from this treasure tale—the media gets a hot human-interest story, the preservation community gets public interest in maritime history, Frankfort gets national and international media attention, Dykstra and Monroe get the public’s encouragement, and people constrained by work or family can live vicariously through their quest for adventure.

Whether or not gold is discovered, the real offshore treasure remains the remarkable collection of shipwrecks that are uniquely preserved in the cold fresh water of the Great Lakes. Our region’s colorful maritime history and lore has fed the imagination of generations. The rich texture of the harbor with its historic structures nestled between the wooded hills and the vast open horizon to the west offers something that other harbors choked with plastic boats and condominiums can’t offer.

Yet, just this month, the rail-ferry loading dock in Elberta—eligible to be considered a National Historic Landmark—was tossed into dumpsters and hauled away, despite numerous adaptive reuse proposals and appeals to save them. No commemorative plaque will ever portray the heavy, riveted steel structure that allowed the very first train to cross the open and unprotected waters of the Great Lakes nor the countless trains after that for a century.

Media may devote headlines and airtime to extraordinary and glamorous legends such as Confederate gold lying off the Frankfort coast. But our local history narrative should not forget the unique history of the rail ferries, the lifesavers, the shipwrecks, and the treasure seekers. If we want to continue to capture the imagination of those who walk our shores, we must make a conscious effort to keep our unique maritime heritage alive and not sit idly by as it is hauled off to dumpsters or spun by the media machine.

Feature photo: A fleet of officially marked state vehicles descended upon Frankfort on the morning of June 9 before disappearing into the fog. Photo by Jed Jaworski.

Jed Jaworski is a regional maritime historian and diver, previously employed with the Michigan Maritime Museum, Manitou Passage State Underwater Preserve, S.S. City of Milwaukee National Historic Landmark, and Northwest Michigan Maritime Museum.

My father was born and raised in Benzie County. I always thought he was telling tall tales when, while sailing at our cottage on Crystal Lake, he talked about a legendary Confederate treasure. Tons of CSA gold, my dad claimed, lay on the bottom of Lake Michigan off Frankfort. He would go on to tell a story about a Confederate vs Union Civil War skirmish in the nearby village of Copemish on the early rail line to Frankfort. Both Bruce Catton and Leonard Case convinced my dad that although this fight had occurred, it was never thoroughly documented. My dad kept me wide-eyed with wonder with the question — were the two legends linked?

Good day:

I am questioning the tear down of the Ferry Dock and that material that was put into a dumpster?

According to the U.S. Dept of Transportation said the Port of Elbert, Michigan Dock was built as a Commercial Deep Water Dock. McCaughrin Maritime Marine Systems, Inc, mccaughrinmaritime.com/whatsold10.htm (February 14, 2008) Petition to State of Michigan to Preserve the 700′ Foot Dock, plus 18 additional acres as Commercial Deep Water Port, State of Michigan Officials said McCaughrin Maritime did not Substantiate the claim and was revoke, but then this State of Michigan shut down Ann Arbor Ferry Line never told anyone they were doing it putting hundred of people out of work . Please Read the Articles..