First licensed U.S. female pilot, queen of the Channel crossing

By P.G. Misty Sheehan

Current Contributor

Earlier this month was the 109th anniversary of a special event for the history of the world, and for our neck of the woods. Harriet Quimby (1875-1912)—who spent her childhood in what is now known as Arcadia Township in Manistee County—was the first woman to fly across the English Channel on April 16, 1912, less than eight years after the Wright Brothers’ historic flight brought flying to the world.

Brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright were the first aviation pioneers to be inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1962. However, it took until 2004 for Quimby to posthumously receive her place in that same hall. She has been celebrated in Northern Michigan for quite some time, though, despite that many readers may not realize one of our own was the first American woman to receive a pilot’s license.

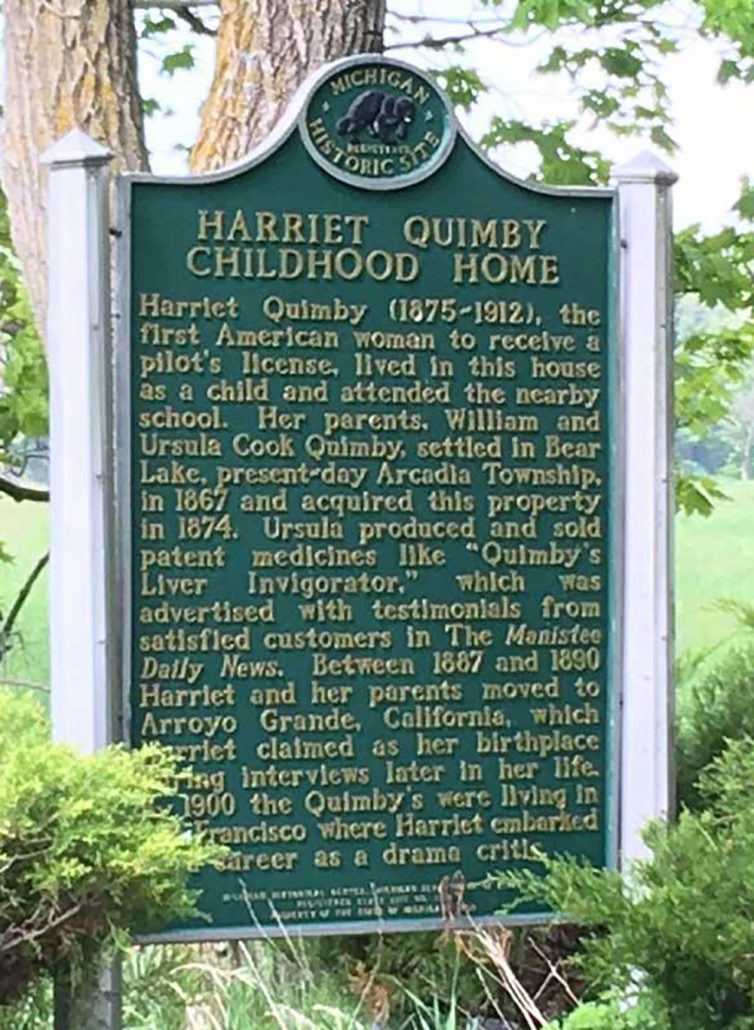

It all started in another era entirely. For his service in the Civil War, Harriet Quimby’s father, William Quimby, was granted 160 acres in Arcadia Township, which he proceeded to clear and farm. Her mother, Ursula Cook Quimby, prepared and sold patent medicines and was known for her “Quimby’s Liver Invigorator.”

On May 11, 1875, Harriet Quimby joined the family—though there is some confusion surrounding her birthplace. What is known is that she grew up in Arcadia Township, until the Quimbys eventually moved from Bear Lake’s Erdman Road to California when the young aviator was just a teenager. (She would, later in life, give interviews claiming that she had been born in California, according to a Michigan History Center plaque in Arcadia Township, and Coldwater, in southeast Michigan, also claims to be her birthplace; additionally, there are various records indicating that the family lived in this area around the time that she was born.)

As an adult, Quimby went from being a journalist for the San Francisco Chronicle to writing for Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly in New York City. She was not an overt feminist but supported women’s rights as editor of the women’s page at Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. In her articles, she gave advice to women on finances, men, and auto repair. She also remembered her Michigan farm heritage when she wrote: “To Americans living in large cities, the danger of over artificiality, of utter divorcement from nature, is very great and it is wonderful how a few plants… will take one back to the days when life was very sweet.”

In addition to being known in San Francisco and New York City as a journalist, she was also a drama critic and screenwriter, with several silent films to her credit.

Additionally, Quimby was recognized for her growing interest in new vehicles—and speed. In 1906, she was the first woman to drive 100 miles per hour. But this was only one of her firsts.

Thrilled by an article on flying, Quimby enrolled in flight school in 1911.

“I’m going for everything that men have done: altitude, speed, endurance and the rest,” she is quoted as having said. After four months of hard work and only 33 flight lessons, she became the first woman to receive a pilot’s license from the Aero Club of America, the U.S. branch of the Federation Aeronautique; there had been American women to fly before her, and there had been French women who had received their pilot licenses, but Quimby became the first woman in the United States to receive a pilot license.

Quimby was a regular on the circuit of exhibition pilots who performed and raced each other throughout the country at that time. In a September 1911 air meet, she won $1,500—an extraordinary amount of money at the time. She also performed internationally, notably at the inauguration of Mexico’s president, where she reportedly was everyone’s favorite.

She was also the first woman to fly at night.

Quimby was known for being very stylish, too. The Arcadia Historical Museum has a version of the one-piece, plum-colored, satin suit that she wore while flying; she also dressed in high heels and a stylish hat when she flew. One person claimed she was “the prettiest girl I have ever seen. She had the most beautiful eyes.” She liked being appreciated, especially for her flying; Quimby had a fan club who followed the “bird girl.”

Everything was not all blue sky and prizes, though.

On one flight, the engine quit. Cool and collected, Quimby just glided into a landing.

She always made sure to take care that everything was checked out before she flew. She explained:

“Only a cautious person—man or woman—should mount my machine until every wire and screw has been tested.”

On April 16, 1912, she approached the English Channel, starting her historic flight from the British side. It was a beautiful day—blue sky. A crowd had gathered to see if she would complete the 22-mile flight across the English Channel. British pilot Gustov Hamel was there with her. She complained:

“I was annoyed from the start by the attitude of doubt on the part of the spectators that I would never make the flight.”

Hamel reportedly made an outrageous offer to switch clothes with her, then fly the plane across the channel for her. His plan had her somehow popping out of the plane in France and taking credit for the flight. Obviously, she refused.

At 5:30 a.m., she lifted off and flew at 6,000 feet. The blue skies disappeared as she approached France, however. Quimby had been given a compass by an admirer and used that to navigate when the clouds obscured her view. She said the mist felt like tiny needles on her skin. She broke free of the cloud bank and was pleased to see a white beach and green fields. She landed one hour and nine minutes later and was surrounded by French farmers and their families, who had gathered to watch her flight attempt.

Despite her achievement, fame did not come to her. Two days before, the Titanic had gone down in the freezing waters of the North Atlantic. This feat of hers—to be the first woman to cross the English Channel—was barely reported.

So, Quimby bought another plane in Europe to fly in the Boston Air Meet on July 1, 1912. She took one of the organizers up for a ride, but the aircraft bucked terribly and both were thrown from the plane. (It is thought the airplane was poorly designed.) She was 37 years old and had flown for less than a year when she died. However, her skill, success and attitude that “flying is a fine, dignified sport for women, it is healthy and stimulating” was a precursor, perhaps even a call, to Amelia Earhart, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, and Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran to fly in her stead.

Harriet Quimby is immortalized by PBS and NOVA television specials and by Onekama Consolidated Schools’ fifth- and sixth-grade students, back in 2000, who created computer reports and wrote biographies of her, the latter appearing online. The schools’ website indicates that third-grade students made posters and a handful of students created a Harriet Quimby timeline. A second-floor exhibit about the pioneer female aviator can be found inside the Arcadia Historical Museum at 3340 Lake Street in Arcadia. For more information, visit ArcadiaMI.com and Archive.Onekama.k12.MI.US/Quimby/Main.htm

A version of this article first appeared in the Freshwater Reporter in August 2020. Reprinted by permission.

Featured Photo Caption: A 1991 U.S. Postal Service stamp commemorating the achievement of Harriet Quimby, who grew up in Arcadia Township.