Northern Michigan daughter strives to bring home MIA airmen from a World War II mission

By Linda Alice Dewey

Current Contributor

My father, pilot Bill Dewey, worked to steady the severely damaged B-24 Liberator, code-named “Wallet-855.” He and co-pilot Bill Boykin had already shut down engine number three. Unable to keep up with the few U.S. bombers left in the air, they had dropped out of the formation that was heading back to England.

Alone now over central Germany, with two and a half hours to go, he radioed Colgate—an emergency radio station in England—for a heading across the English Channel, then he sent Boykin to the rear of the plane to assess the situation. From the way she was flying, #855 was in bad shape.

Dewey prayed like he never had before. Then suddenly, all the fear and anxiety disappeared, and a huge wave of peace came over him, almost as if someone else had come in and was flying the plane through him.

Boykin returned with the report: cables frayed to the breaking point, tail shot up, rudders barely holding. Wind rushed in through a three-foot hole in the waste, buffeting the bomber. As for the crew, the tail gunner’s face was covered in blood, and both waist gunners might be dying.

By this late date in the war—September 27, 1944—the struggling Luftwaffe (the German Air Force) had planes but few pilots. The Allies had declared air superiority over Europe. As a result, very few of this batch of American flyboys had ever seen—much less shot at—a German fighter.

Dewey’s crew was on its eighth mission. Kassel was supposed to be an easy assignment, but the group’s lead plane had unexpectedly veered from the division, taking the rest of the 445th Bomb Group with it,and dropping its payload near Göttingen—30 miles away from the central German city of Kassel—instead.

German ground control saw Dewey’s lone group of 35 stragglers, which would be easy to pick off. Four groups of elite German fighters—Sturmgruppen—were directed for the kill; included in the four groups were 150 Me-109s and FW-190s which attacked, wing-to-wing, in waves of 10 to 15 abreast.

Dewey’s earphones came alive with action reports from his crew. He felt the first hits, then the rudder pedals became mushy. A blow on the right, and #855 jumped left, then began to bump around heavily in the air. The plane vibrated from his own gunners, shooting at five fighters on their tail.

The “lightning strike”—lasting a mere six minutes—ended when American fighters arrived, pulling off the enemy into spectacular dogfights. One American fighter pilot died; another became an “ace-in-a-day” by downing five Germans.

But only four of the 35 bombers made it safely back to the base in England—of the 336 men flying in them, one-third died and more than one-third became prisoners of war. The rest eventually straggled to the base at Tibenham, near Norwich, England.

It would go down in history as the worst loss for a single group in a day’s battle ever—a U.S. Air Force record that still stands today. Meanwhile, the German toll was 18 pilots and 32 fighters lost. In some ways, the burden was worse for them, though: they did not have more pilots, whereas the United States had plenty of replacements.

That day, Bill Dewey was flying a Ford-made B-24 Liberator, made at Willow Run, near Ypsilanti. The war effort in southeast Michigan bore the term: “Arsenal of Democracy.”

For my father, flying the B-24 was flying a piece of home, since his family had relocated to Detroit from Chicago when he was eight years old. He had attended The Leelanau School in Glen Arbor during his sophomore year, and he later graduated from Detroit’s Redford High School, then followed his dream and worked for the railroad until he joined the service.

Reunion with Former Enemies

I am the oldest of Bill and Marilyn Dewey’s three children. Born in 1948, my first memory of hearing about the Kassel Mission is when my father told us the story one night at bedtime; I never forgot it. When I was four, our family began to summer in Glen Arbor; Dad commuted every weekend from Detroit.

As I was growing up, Dad never joined any veterans’ groups. Then, 40 years after the war, he attended a few reunions, and he even sought out other survivors of that harrowing mission, which had been so pivotal for him—he had entered the Air Force as a soft private, and he had exited as a captain and group assistant operations officer, also known as a “briefing officer.”

At a 1987 reunion in England, Dad finally met others who had lived through the Kassel Mission—navigator Frank Bertram and his pilot, Reg Miner. The three walked the tarmac at Tibenham, sharing their stories.

For Bertram and Miner, the story was that they had both gone down and been captured as prisoners of war. A group of local Hitler Youth had found and captured Bertram the day after he crashed, led there by then-12-year-old Walter Hassenpflug and a friend who had witnessed the lead 445th bomber crash. Fast-forward many years later, Bertram and Miner planned to fly to Germany to meet former-Hitler-Youth-turned-local-historian Hassenpflug, who had reached out to find Frank Bertram. (After their meeting in the late 1980s, the two remained friends until they died a few years ago.)

Dad was entranced by this upcoming meeting between captives and captor; the war was more than four decades old, and he had always wanted to meet the men who had flown against them. He felt they were just doing their jobs, like he was just doing his.

Two years later, the Eighth Air Force News magazine published two issues in 1989 that were full of accounts from Kassel Mission veterans—both American and German. Dad suggested that the editor compile it all into a booklet. The editor replied, “Why don’t you do it?” and sent the material to Dad, who was now living in Birmingham, Michigan.

One “letter to the editor” in those materials had asked about the possibility of erecting a memorial to the battle. After shopping it around, Dad felt like the Americans liked the idea, so he wrote to Walter Hassenpflug to see if the Germans wanted to collaborate, and he asked if there was an appropriate location.

As it turned out, Hassenpflug knew just the spot.

It would be the first time in history—as far as we know—that former enemies would collaborate to create a war memorial dedicated to all who died in a battle. And it had been Dad’s idea to take it that extra step: to go from a memorial for just one side to a joint memorial.

To raise funds, the Americans created a new 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, the Kassel Mission Memorial Association (KMMA), now the Kassel Mission Historical Society (KMHS). They published that booklet of first-hand accounts that had been collected by the Eighth Air Force News, and they sold it for $10 apiece.*

Then in November 1989, the wall dividing East and West Germany fell; Kassel is located near the border between what, after World War II, would become East and West. Half the planes from the Kassel Mission had fallen on each side.

The next summer, in 1990, more than 500 people gathered at the crash site of the lead 445th bomber, now a newly created park, to dedicate the memorial. Seven German and U.S. Kassel Mission veterans pulled aside the drapes covering the monuments, then shook hands. Finding themselves in a circle, they spontaneously joined hands and raised them in triumph, in enemies becoming friends, and in a salute to their fallen comrades.

The next day, Sturmgruppen pilots, German civilians, and their American guests toured many of the 25 crash sites in the area, all mapped and researched by Hassenpflug. At each stop, those involved met one another and told their stories. When they crossed into the former East Germany, town bells rang as villagers turned out to welcome the first Americans they had seen since the war.

At home later, I watched Dad’s tapes of these trips, and I was struck by the magnitude of what had occurred.

In 2004, he stepped down from running the nonprofit organization, and I became president of Kassel Mission Historical Society. Two years later, I accompanied Mom and Dad back to Tibenham and to a rededication of the memorial in Germany, which was again attended by 500.

That was his last summer. Dad passed away the following March, in 2007, having accomplished so much, though he never wrote his intended book about the Kassel Mission. However, over the last five years of his life, I interviewed him many times about the experience.

Ongoing Issues

I stepped down as president of the nonprofit in 2018, but I continue to advise the board. And things have heated up for the KMHS since January 2021, when I renewed a campaign to bring back the suspected remains of our eight Kassel Mission airmen who went missing in action.

Of the eight MIA Kassel Mission battle airmen, one is believed to still be in Germany.

Remains of two more are buried as “Unknowns” at the American military cemetery in Tunisia, where the political situation also hampers recovery.

The remains of five more MIAs from the mission were recently disinterred in Germany in 2015, after KMHS helped the DPAA. (The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency is an agency within the United States Department of Defense whose mission is to recover U.S. military personnel who are listed as “prisoners of war” or “missing in action” from designated past conflicts from countries around the world.)

From Glen Arbor this winter, I conducted Zoom meetings that matched family members of the MIA with an international team of researchers and archaeologists. (Not only Americans, but Russians, Italians, Canadians, and British are all buried at the POW burial ground in Germany, so those governments are involved, too.) These remains have been exhumed, and we believe that they are now being processed for identification—these graves are unmarked, a situation oddly similar to our recently reacquired cemetery here in Glen Arbor, where Civil War veterans lie. Both endeavors require ground-penetrating radar to locate the graves.

Across the Channel

Bill Dewey lowered #855 through light cloud cover over the English Channel. Straight ahead lay those wonderful White Cliffs of Dover and that long emergency landing strip just beyond.

Now came the moment of truth. Dewey gave copilot Bill Boykin the order to lower the landing gear. The hydraulics worked beautifully—even with all the bumping around in the air, they touched down smooth as could be. The landing gear held; the tires stayed inflated. It was his best landing ever, “like landing on feathers,” as he would later describe it. Ambulances ran alongside as the Liberator slowed, then stopped.

Dewey went back to check his wounded, who were lifted out on stretchers through the hole in the waste. As the rest of the crew disembarked, an Air Force photographer ran up, saying he had never seen such a damaged plane stay together through a landing. He begged them to disembark again for the camera. Dewey did not want to, but his co-pilot said, “Aw, c’mon, Bill,” so they did. Then they walked around the ravaged Liberator, surveying the damage—bullet holes everywhere, rudders hanging by threads, the ragged shot-up tail.

But his gunners all lived. One was sent home; the others returned to fly with him again.

We never did see those pictures, but all those original letters and pictures forwarded by the Eighth Air Force News—and more—are safely packed in a climate-controlled facility right here in Traverse City; and a piece of #855 sits in my Glen Arbor home, where I paint and write his-story and work to bring home those MIAs.

*The Kassel Mission Reports is available in PDF format at KasselMission.org/PX online. Read accounts and learn more about the Kassel Mission at the KasselMission.org website; you can also join the “Kassel Mission Historical Society” group on Facebook. The German and American Airmen’s Memorial is located in the wooded hills near Ludwigsau, Germany.

Artist Linda Alice Dewey is the author of Aaron’s Crossing, which starts out at the Glen Arbor Township Cemetery, and The Ghost Who Would Not Die. Both are available at local bookstores and on Amazon. See her artwork at LindaAliceDewey.com online.

A version of this article first published in the Glen Arbor Sun, a Leelanau County-based semi-sister publication to The Betsie Current.

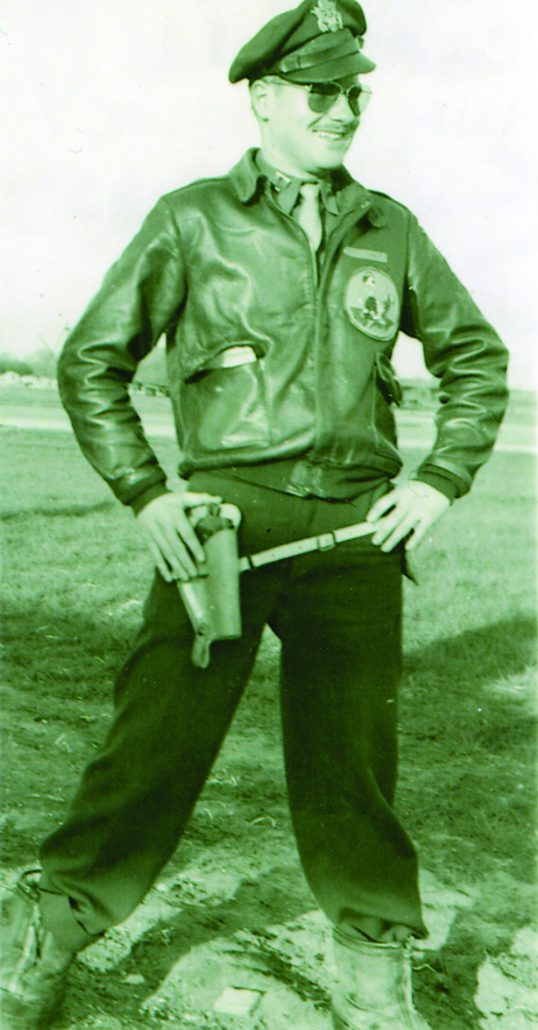

Featured Photo Caption: Air Force Captain William “Bill” Dewey at the controls. He was one of few survivors from the Kassel Mission over Germany, which was supposed to be an easy assignment. More than four decades later, Dewey led the charge to erect a memorial in Germany that would honor both sides who had fought on September 27, 1944. Photo courtesy of the Dewey family archives.