Outsized community role

By Keith Schneider

Current Contributor

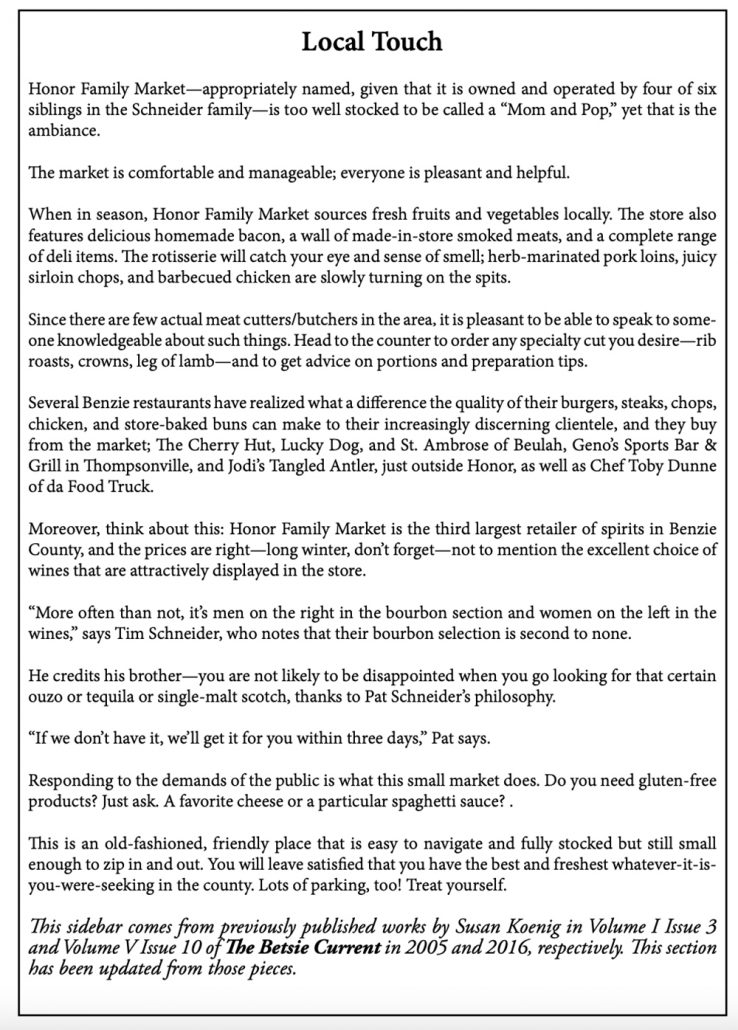

The choreography inside a small, independent, rural grocery store is on display daily at Honor Family Market. Tim Schneider—one of four siblings, all in their 60s and 70s, who own and manage the store—stacks packaged goods in one of the seven aisles. Younger brother Patrick Schneider prepares prime cuts of beef and homemade sausage behind the butcher’s counter. A sister, Marilyn Edginton, oversees the bakery. Her younger sister, Helen Schneider, manages the produce department and oversees accounts, ordering, and payroll in the office.

Because it is the only market in town, it has an outsized role in this community of 330 residents. The 12,000-square-foot store, its shelves filled with local products like honey, baked goods, and homemade bratwursts, is not only a place where people—in Honor and elsewhere in Benzie County—go to buy meat, wine, beer, and produce. It is also where they can go to get free, or at a reduced cost, food and supplies for community events, like football games in the fall or the annual National Coho Salmon Festival in the summer.

“It’s paramount for a healthy, living, breathing community,” says Ingemar Johansson, a resident and president of Honor Area Restoration Project (HARP), a nonprofit business development group. “Everybody shops there. You run into somebody you know every time you go.”

The store employs nine full-time and nine part-time workers; hundreds of Honor’s high school students have worked their first jobs in the store, sweeping the well-worn linoleum floor, stacking groceries in the narrow aisles, or bagging at the three checkout lanes. The market’s location in the small shopping plaza along US-31 makes the market convenient to hundreds of workers who commute between Benzie and Traverse City.

“We’re an independent grocery store that knows its customers and what they want,” Tim Schneider says. “The value of our store is the fact that it’s close to a lot of people in how they live and where they live.”

Confronting Trend in Grocery Economy

How long the Honor Family Market remains a local institution, though, is far from assured.

The Schneiders are ready to join the mammoth tide of 9 million Baby Boom business owners that are retiring. They hope to keep the store independent—a herculean task during a time of industry consolidation that has pushed up grocery prices.

Curtis D. Kuttnauer—managing director of Golden Circle Advisors, a Traverse City-based investment bank that specializes in selling small businesses—says that the Schneider’s goal is impeded by powerful headwinds in and outside of Northern Michigan, including consolidation in the grocery sector, tight lending for low-margin businesses, and the well-researched difficulty of selling small, rural businesses.

Keeping Honor Family Market independent, in effect, requires a buyer who is willing to not only take on the tight margins of a small business but also compete against the giant chains. For instance, the Dollar Tree—located right next door in the plaza—competes for sales of toiletries, paper goods, detergents, and snacks.

“Three-quarters of businesses put on the market don’t sell,” Kuttnauer says. “What makes rural businesses more difficult to sell is that most need to be operated locally; being rural limits the pool of buyers.”

From 1990 to 2015, the number of independent grocery stores in the United States dropped 39 percent to 2,648, with an average of 30 stores closing every year, according to a 2021 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

That suggests there are roughly 300 fewer stores today than in 2015 nationally. Several of those local groceries that closed are near the Honor Family Market: Deering’s Market in Empire closed in 2018; Gabe’s Market in Maple City closed in 2019; Kaleva Meats closed in 2019; and the Schneiders’ Copemish Family Market closed in 2021.

Virtually all independent groceries operate within tight margins in a hypercompetitive $846 billion industry in which a significant portion of all grocery sales goes to just four companies: Albertsons, Costco, Kroger, and Walmart.

Weakening Competition, Hurting Small Grocers

The Schneiders have certainly felt the whip of consolidation. The number of wholesale food distributors that served their grocery in the 1990s diminished from seven in the region to one in Grand Rapids, owned by Spartan Foods—which notably owns and operates two Family Fare chain stores in Benzie County and 79 other grocery stores in Michigan.

In other words, Honor Family Market is captive to Spartan Foods’ pricing.

“Walmart doesn’t want to sell to me; Meijer only does its own stores,” Tim Schneider says. “Spartan is pretty much it.”

Rial Carver directs the Rural Grocery Initiative at Kansas State University.

“It’s a big challenge,” Carver says. “Rural grocers have fewer options for stocking their stores, and they are at a competitive disadvantage with supercenters and discount retailers. We’ve seen the number of independent grocers has dropped 15 percent over the last decade or so.”

The industry’s concentration, economists have said, was allowed to happen largely by decades of weak enforcement of antitrust laws, particularly the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, which forbids price discrimination that could wipe out competition in an industry.

“For the next almost 50 years, the Federal Trade Commission vigorously enforced the law,” says Stacy Mitchell, an expert in monopolies and a co-executive director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a nonprofit group that provides technical support to communities for sustainable development. “For all those decades, the market structure was about half independent grocers and about half chains.”

But that started to change in the 1980s, when the FTC “suspended enforcement,” Mitchell says, because President Ronald Reagan (R: 1981-1989) and several other administrations that followed saw improving efficiency with larger grocery stores as a priority over ensuring competition.

In addition to the Dollar Tree in Honor and the two Family Fares in Benzonia and Frankfort, there are nearly a dozen discount dollar stores in and around Benzie County: a Dollar General in Copemish, Interlochen, Kaleva, Long Lake, Thompsonville, two in Bear Lake, one more in Springdale Township, as well as just outside Frankfort and along US-31 between Honor and Interlochen; there is also a Family Dollar in Benzonia. (Editor’s Note: The Betsie Current published an article by Jacob Wheeler on dollar stores in December 2019; read in our online archives. Also check out Wheeler’s most recent update to this ongoing story online.)

Resolve to Stay Open

The Schneiders are experts in navigating the changing economic landscape of the grocery sector. They were raised in the business by their father, Leroy Schneider, a career food service manager—Roy and Rose Schneider sold the Eastfield Thriftway in Traverse City in 1974 when they “retired,” though they kept their hands in the family business many years later.

The Schneider siblings bought their first grocery store in 1980 in Copemish—a similarly tiny town, located just 15 miles south of Honor—for $175,000. They bought the store in Honor from Chuck Link in 1992 for $400,000.

Slower sales during the pandemic, and the family’s desire to shrink their scope of work, prompted the Copemish store to close in 2021—the family would have preferred to sell the store, but they never found a buyer. So the Schneiders retained ownership of the 15,000-square-foot building that now serves as a vehicle warehouse for Crystal Mountain Resort, the county’s largest private employer.

The family also put the Honor store on the market that same year, in 2021—now listed for $1.1 million—and subsequently hired and fired three brokers. But the lone buyer who expressed interest in the Honor store failed to show up at closing in 2023, because of a lack of funds.

The Schneiders say the market resistance is surprising, given the sturdiness of the economy in Benzie County and across the rural northern counties close to Lake Michigan.

Since the start of the century, Benzie County’s population has increased about 15 percent to more than 18,000. Many of the new residents who arrived during and after the pandemic are wealthier members of the Baby Boom and Gen X.

Since 2019, the county has added nearly 400 new jobs—an 8 percent increase—and is among the five fastest-growing labor markets in the state, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

And it is not just seasonal summer work.

Winter unemployment—which soared to 19 percent here in the early 1990s—dropped to 6 percent earlier this year, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Not that long ago, household incomes in Honor were under $45,000 a year, most residents were graying, and the largest building in the worn business district was an abandoned turn-of-the-20th-century Masonic Lodge.

The village now is a display of the stronger economy.

The dilapidated lodge is gone, replaced by affordable townhomes. A 52-acre, $1 million town park—paid for with state, foundation, and donor funds—opened last summer along the banks of the Platte River, which flows through the village. (Editor’s Note: The Betsie Current published a piece by Keith Schneider on the new Platte River Park in May 2024; read in our online archives.)

In September, TrueNorth, an Ohio-based company, opened a gas station and convenience store, while a new coffee shop, Weldon Coffee, also opened.

In November, Sleeping Bear Motor Sports, a motorcycle and recreational vehicle dealer, moved from Interlochen to a newly renovated building in Honor.

Even two of Honor’s specialty businesses, the Cherry Bowl Drive-In Theater, one of the last of Michigan’s outdoor movie theaters, and Field Crafts, a screen printer, completed sales last year to new owners.

The question becomes: will the Honor Family Market sale go through?

For 33 years, the Schneiders’ full-service market has served enough essential purposes as a source of food, employment, and civic gathering that few Honor residents can imagine anything other than every day, without interruption, its doors opening at 9 a.m. and closing around 6 p.m., except for Sunday, when they shut three hours earlier.

As Marilyn [Schneider] Edginton bakes fresh bread for the lunch crowd, Tim Schneider stacks packaged goods. Patrick Schneider tends to customers from behind the spotless glass of his meat counter. The digital cash registers, which Helen Schneider manages, chirp at the checkout lines up front.

“We’re staying until we sell—we’re agreed on that,” Edginton says. “The next owner is going to have new ideas and things they want to do when they buy this store. It’s really not that hard. Stuff comes in the back door. We put a price on it, move it to the middle, send it out the front, and hopefully we make some money.”

A version of this article was published by The New York Times on January 14, 2025. Keith Schneider, although having the same last name, is not related to the Schneider family who own Honor Family Market.

Honor Family Market is located at 10625 Main Street/US-31 in Honor. Call 231-325-3360 or email honorfamilymkt@centurytel.net for more information. Learn more at “Honor Family Market” on Facebook.

Featured Photo Caption: Patrick Schneider (left) and Tim Schneider (right) are two of the four Schneider siblings who have owned and managed the Honor Family Market since 1992. Photo by Keith Schneider.