The wreck of the St. Lawrence appears

By Jed Jaworski

Current Contributor

When walking the sandy, windswept shores of Point Betsie—with the weathered bones of shipwrecks and the solitary sentinels of the lighthouse and lifesaving service buildings there—one cannot help but to think of the past.

What ships passed by, and who were the sailors and passengers aboard them? What were the lives of the people like whose lonely vigil it was to guide and protect the ships? What events or great storms may have brought these people together?

These stories can often be told by relics—lying unseen beneath the water and shifting sands—which sometimes appear out of nowhere.

One Such Tale

In the summer of 1985, a Frankfort resident was swimming at Point Betsie when he saw a strange sight beneath the waves. The object was dark, man-made, immense, and looming—it took his breath away. He reported the sighting to the State. Historians and archeologists soon arrived on site to determine that the entire port bow of the long lost steamship St. Lawrence was coming ashore at the Point.

The St. Lawrence had struck bottom and sunk south of Point Betsie in 1898, but the wreck had vanished shortly after. Disappearing beneath the waves, it had not been seen since. The wreck and rescue of the steamer St. Lawrence was one of the most dramatic rescues to have occurred at the Point, but time acted just like the sands that buried the wreck—concealing the story for nearly a century. More recently, with the dramatic discovery of the wreck reappearing, the story of the St. Lawrence was also coming to light…

Thanksgiving eve of 1898 provided the anticipation of a special day that would break the monotony of a lonely existence for the handful of people living at the Point. There was the lighthouse keeper and his assistant, with their families, living at the lighthouse. The light keepers kept the lighthouse lantern burning and sounded a steam fog signal if visibility became reduced.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Lifesaving Service buildings and personnel were just south of the lighthouse. Captain Harrison Miller was in command of seven “Surfmen,” as they were sometimes called. When not engaged in the constant maintenance of grounds, buildings, and equipment, they practiced their lifesaving and seamanship skills. In the summer months, tourists would come to watch them practice drills and to visit, but fall was a lonely vigil, save for the excitement of fearsome November storms for which the Great Lakes are infamous. Every day and night, Surfmen would patrol the beaches north and south, as well as maintain a lookout in the watchtower. The passing of ships and weather was noted in the daily log book.

On this Thanksgiving eve, the weather was taking a dramatic turn with rising winds and snow beginning to fall.

Upbound on Lake Michigan was the steamer St. Lawrence. Built in 1890 of sturdy white oak and reinforced with steel, the St. Lawrence was one of the larger wooden ships on the Great Lakes at 239 feet in length. The vessel carried 64,000 bushels of corn, bound from Chicago to Prescott, Ontario.

Captain Albert Senghas was confident in the seaworthiness of the staunch ship as the waves grew taller, but he was apprehensive about the approach of Point Betsie and the treacherous Manitou Passage with the loss of visibility in the now blinding snow.

Heavily laden, the ship was drawing 20 feet of water; as such, Captain Senghas needed to steer well clear of Point Betsie in the deteriorating weather. The ship’s lookout was intently listening for the lighthouse fog signal, but the heavy snow muffled even the sounds of the waves crashing into the bow of the ship. Suddenly, the St. Lawrence struck bottom. The ship was hard aground and now pounding on the bottom with the passing of each wave.

Ashore at the Lifesaving Station, two miles up the coast, the Surfmen’s Captain Miller was mulling the intensifying wintery storm when he heard the faint sound of a steamship’s distress whistle. Captain Miller and the Surfmen sprung into the action that they had tirelessly rehearsed for; they started down the beach with the heavy surfboat and breeches buoy cart in the difficult soft sand and snow. They could scarcely see three feet in front of them with the blowing snow and could only use the sound of the St. Lawrence’s distress whistle to guide them.

Just before coming abreast of the wreck, over a mile down the beach, a man was sighted face down in the surf. The lifesavers quickly brought the man up onto the beach, but it was apparent he was dead, having taken a blow to the head when the lifeboat he was in capsized in the surf. Others were soon found, helped from the icy waters, and quickly were sent back to the station where Captain Miller’s wife and children gave them hot drinks, food, and blankets.

Captain Miller now faced a perilous situation, and he needed to act quickly before more people panicked and attempted to come ashore through the deadly surf in lifeboats.

He was directly on shore from the wreck but could not see it, otherwise he would have fired the Lyle cannon that would take the rescue line—needed to rig the breeches buoy or life car—and bring people safely ashore. Faced with this predicament, Captain Miller, against all odds, decided to skillfully aim the Lyle cannon in the direction that he heard Captain Senghas’s distress whistle. With a muffled boom, the cannon shot the projectile with the line attached into the snowy white abyss toward the ship.

Captain Miller awaited a response from the crew aboard the ill-fated St. Lawrence, but there was none. He then ordered a second line to be rigged and fired again; this line was lost. The first line was then pulled in to be re-fired, but after a short bit, it came up taught. Interestingly, each time the Surfmen pulled the line taught, the ship’s whistle would blow.

Aboard the St. Lawrence, Captain Senghas was attempting to find out who, or what, was blowing the ship’s whistle outside of his authority. At that moment, he discovered Captain Miller’s first rescue line had fired true, landed directly over the middle of the ship, and had taken hold on the whistle’s pull cable going from the wheelhouse aft to the whistle on the smokestack. Thus alerted to the line, Captain Senghas and his 13 remaining crew were able to properly rig the line and help facilitate the safe rescue of all aboard, Captain Senghas being the last to leave the ship.

Everyone, bitterly cold and wet, made their way back up the beach through the blanketing snow to the Lifesaving Station for much needed shelter and warmth. Though one life was lost, everyone else from the St. Lawrence successfully recovered from the ordeal and gave an extra measure of “thanks” on Thanksgiving morning to the Point Betsie lifesavers.

Returning to the site to recover lifesaving equipment and inspect the wreck, the St. Lawrence was seen to be in dire straits. When the weather permitted, the salvage tug Favorite arrived on the scene, but the vicious pounding of the waves had caused irreparable damage, and the St. Lawrence was given up as a total loss.

Additional fall storms broke the ship asunder, and the corn washed ashore to the benefit of many local farmers and citizens. The following spring, the boiler, engines, and anything of value that could be recovered from the depths was removed by salvage interests. The St. Lawrence then faded into history beneath the sands of the lake bottom—until 1985.

Modern-Day Preservation Lessons

As 1985 wore on, the massive artifact from the past—the St. Lawrence’s port bow—was working its way ever closer to shore. It began to be pummeled in the surf. Worse yet, it would shortly be striking the steel seawall extensions that protect the Point Betsie Lighthouse.

No one was entirely certain what should be done, but neither the destruction of the artifact nor the lighthouse seawall was viewed as desirable.

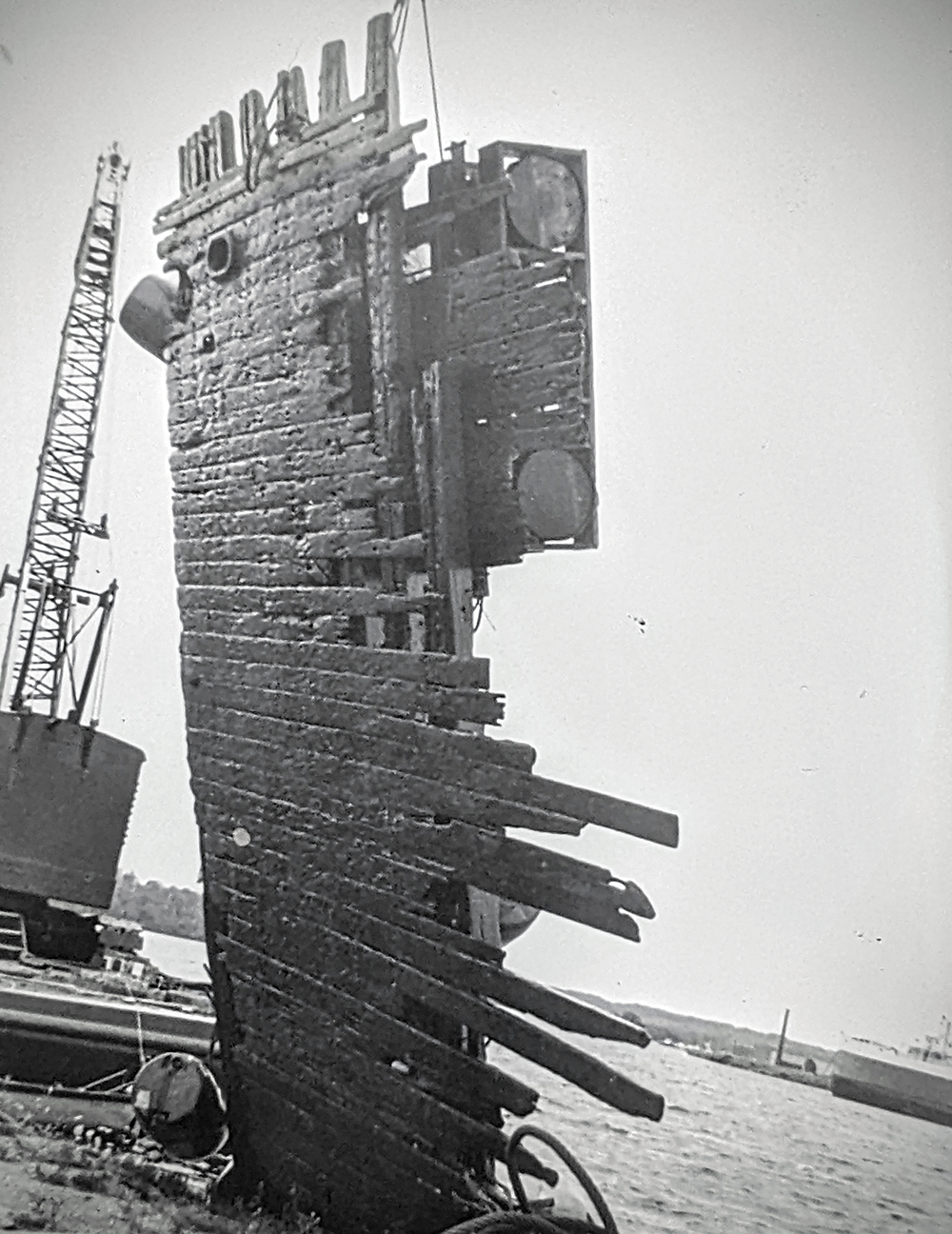

Consequently, the Northwest Michigan Maritime Museum, Inland Seas Marine, Luedtke Engineering, and the Coast Guard Station of Frankfort worked collaboratively to recover the bow before its destruction. Towed into Frankfort harbor, television cameras recorded the impressive sight as the bow rose from the water, much as it would have looked when intact on the St. Lawrence.

The artifact was fully documented and recorded by scholars, then was exhibited for five years outdoors in downtown Frankfort. When the National Landmark Maritime Park proposal at the Ann Arbor car ferry terminal in Elberta was denied, the bow—too large and heavy for most museums—had no place to go. It was then decided to put it back in the lake, but the State of Michigan would not issue a permit. Eventually, it became too unstable to safely move and succumbed to the elements; a hard lesson learned for preservationists.

Since that time, pieces of shipwreck would occasionally be reported along the coast as far north as western Platte Bay. Steel strapping—a unique feature of the St. Lawrence’s construction—allowed marine archeologists to easily associate the wreckage with the ship.

Then surprisingly, in the spring of 2009, an airplane pilot reported a large shipwreck south of Point Betsie—the entire St. Lawrence wreck site had been uncovered from the lake bottom with the shifting coastal dynamics in 21 feet of water.

Again, local and regional teams visited the site and were able to document the wreck, including a photo mosaic. Just months after this work, the sands began to reclaim the site, and it now sleeps deep under the lake bottom again, where—perhaps sometime in the distant future—the wreck and its story will re-emerge for another generation to discover.

The story of the St. Lawrence is told through an exhibit with photographs and artifacts at the Point Betsie Lighthouse Visitor Center. Visit PointBetsie.org for information and hours of operation. Additional history about Point Betsie can be enjoyed at the Benzie Area Historical Museum and the Benzie Shores District Library; you can also tour a fully restored and equipped lifesaving station museum, operated by the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, at Glen Haven.

Featured Photo Caption: The bow of the St. Lawrence emerged out of the water in Frankfort in 1985, the first time it had been seen in 87 years since the ship went down in 1898. The ship’s anchor hawse pipe can be seen in the upper left. Lift drums used to recover the piece are attached inside the hull on the upper right. After five years on display in downtown Frankfort, the artifact was put back in Lake Michigan, as it was too large and heavy for most museums, so it had no place to go. Eventually, it became too unstable to safely move and succumbed to the elements; a hard lesson learned for preservationists. Photo courtesy of the Northwest Michigan Maritime Museum.

Great story…..all new to me!!