Reconciling with the past

By Norm Wheeler

Current Contributor

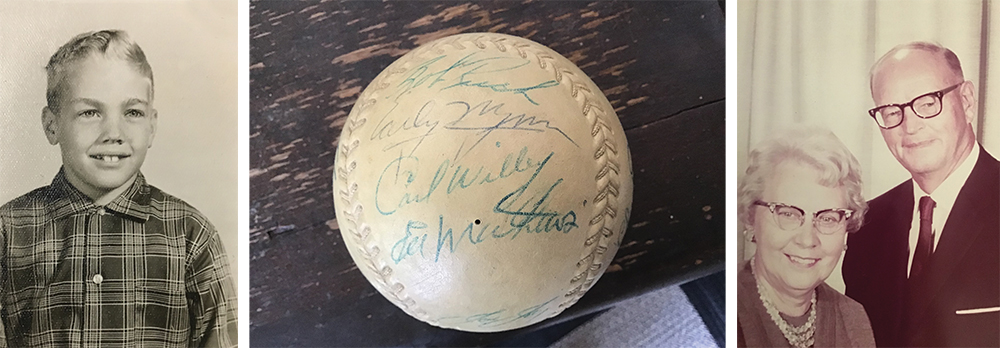

When I was eight years old in 1960, I rode with my grandparents, Hattie and Peter Brondyke, from Muskegon, Michigan, to Bradenton, Florida, so that they could look for a house trailer for them to buy in a trailer park upon his coming retirement five years later.

Grandpa had bad eyes, so Grandma drove the Chevy on two-lane roads all the way—down through Kentucky and Tennessee and Georgia, through every Main Street town and village, and past old country general stores, where hams were hanging from porch rafters and old Black men rocked and smoked their corncob pipes. It was the Jim Crow South, so there were separate bathrooms that said “Colored,” and the little motels where we stayed said “Whites Only.” I was wide-eyed, taking it all in and marveling at the broadening southern drawl.

In Bradenton, we went to the ballpark where the Milwaukee Braves were having spring training, as my grandfather was a huge baseball fan. There was only the one diamond with the old stands around the infield, and all of the players were out there doing drills, playing pickle, and practicing their slides as they took turns with batting practice. I chased the foul balls back behind the stands when they escaped the diamond and threw them back onto the field.

We had a rubber-coated softball along, and we would call out to ask the players for their autographs. I still have that ball, though the ink has faded over the 60 years and some of the names are hard to read. It has Warren Spahn, Eddie Matthews, Del Crandall, Red Schoendienst, Chuck Dressen, and some of the 1960 Chicago White Sox—including Luis Aparicio, Al Lopez, and Early Wynn—from when we went to see them practice just down the road in Sarasota.

One day, Hank Aaron was walking by with Billy Bruton. My grandpa called out, “Hey boy, come sign my grandson’s ball!” Aaron gave him the side-eye, shook his head, and kept on walking. Subsequent days, he still refused to acknowledge us or sign the ball. My grandmother scolded my grandfather, and I learned right there in Braves Park about the toxic, icy nightmare of racism and how it poisons us. I will never forget the look in Hank Aaron’s eye. I have long since forgiven my grandfather, and I have ever since admired the dignity and strength of Hank Aaron and all of the people he inspired.

I hoped someday to show him that ball, to apologize to him, and to tell him my story. Now it is too late. May he rest in peace.

Born in Alabama, Henry “Hammerin’ Hank” Aaron was an American professional baseball player, a right fielder, who played 23 seasons in Major League Baseball, from 1954 through 1976; 21 seasons were with the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves and two were with the Milwaukee Brewers. He also spent time in the Negro American League, from when baseball was still segregated. Aaron—who died on Friday, January 22, at the age of 86—is easily considered one of the greatest baseball players of all time, with 755 career home runs. He was the first to break the home-run record that had been set by Babe Ruth 32 years earlier—though this was not without controversy, since Ruth was a white man. Aaron received death threats and hundreds of thousands of “hate mail” letters during the 1973-74 season for his accomplishment. Having faced racism both before and after this record-breaking season, Aaron was a champion of the civil rights movement throughout his life, and he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from U.S. President George W. Bush in 2002. Even so, when Aaron spoke to USA Today in 2014 about the fact that he had kept every piece of “hate mail” he had ever received, a new batch of the same vitriolic letters were sent to the newspaper’s office, proving that we still have a long way to go toward overcoming our age-old problems of race in America.