A Northern Michigan ghost town and America’s favorite pastime

By P.G. Misty Sheehan

Current Contributor

Ghost towns—sometimes called “boomtowns”—were formerly bustling communities where a natural resource, such as gold, was exploited and subsequently depleted, then the town was quickly abandoned. Most people are aware of Wild West ghost towns, such as California’s famous Tombstone or Bodie, but they are generally unaware of Northern Michigan’s host of ghost towns, built not upon gold but upon timber.

Aral is one such Michigan ghost town. If you have ever put on your bathing suit to go swimming at Otter Creek/the dead end of Esch Road, just off M-22 in the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, you have driven past the old schoolhouse and continued down the main street of that ghost town to the beach, and you just did not know it.

Located four miles south of Empire, Aral’s history dates back to 1853, when Orange Risdon, a surveyor from Saline, Michigan, performed federal surveys in Northern Michigan. Back then, the government required surveys before land could be released for individual purchase.

Risdon liked the mouth of Otter Creek so much that he and his wife, Sally, purchased 122 acres there shortly after his surveying was completed. The acreage was then sold a little over a decade later to Robert F. Bancroft, who served in the Civil War as a photographer. He cleared 20 acres, built a log cabin, and planted black locust trees and an apple orchard.

But lumber speculators also soon came north, having cleared most of the white pine forests near Grand Haven and Muskegon.

By 1881, a two-storied mill was located across Otter Creek on the south side. (The foundations are still there, but they are covered with poison ivy in the summertime, so exploring is not recommended.) Otter Creek was dammed to create a mill pond to receive cut logs that were floated down the river, then cut up at the mill and sent down Lake Michigan, mainly to feed Chicago’s growth.

During the lumbering era, Aral boasted of two boarding houses, a church, and a general store. In 1883, a post office was built, so the community had to decide upon a town name. Though the logical choice was “Otter Creek,” as it was known to its inhabitants, this name, as well as “Bancroft,” after the area’s first resident, had already been given to other communities in Michigan. So a sawmill worker suggested the name “Aral” after the large and salty Aral Sea in Central Asia, and the name stuck—although locals continue to call the area “Otter Creek” to this day.

The town was good-sized, with about 200 people. The “shanty-boys,” the lumbermen, lived on the south side of the river. In 1899, the mill burned down—a suspected arson—and the town shrank in size and importance.

The post office closed, and by 1904, the entire community, with the exception of the Bancroft family, had left.

However, another group moved in almost a decade after the mill fire and briefly revived the town.

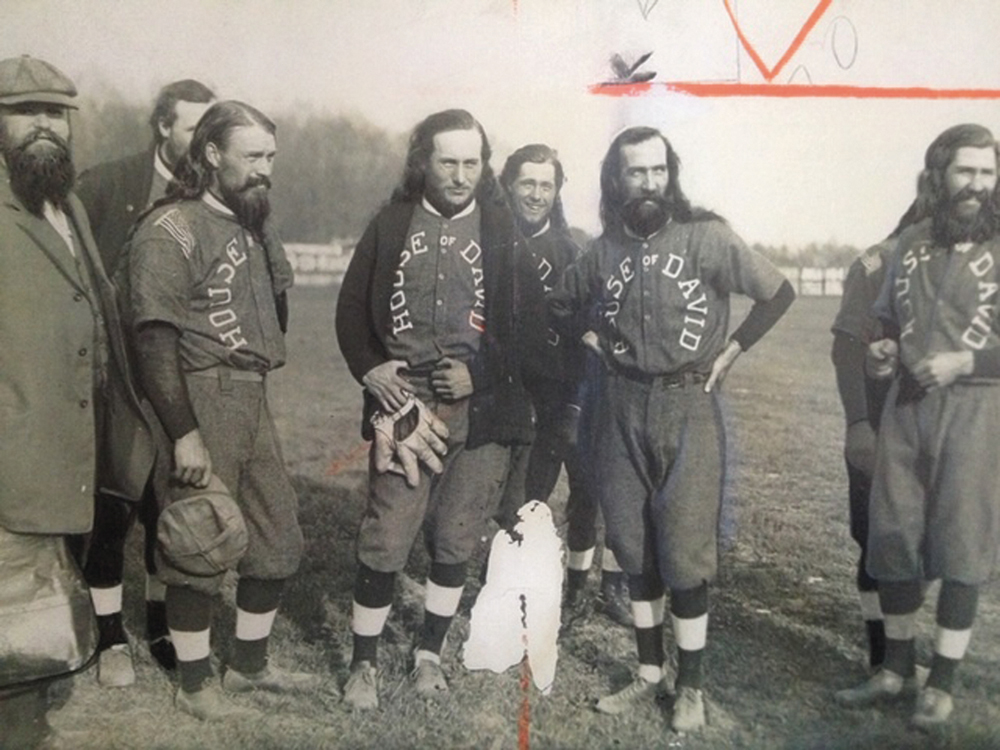

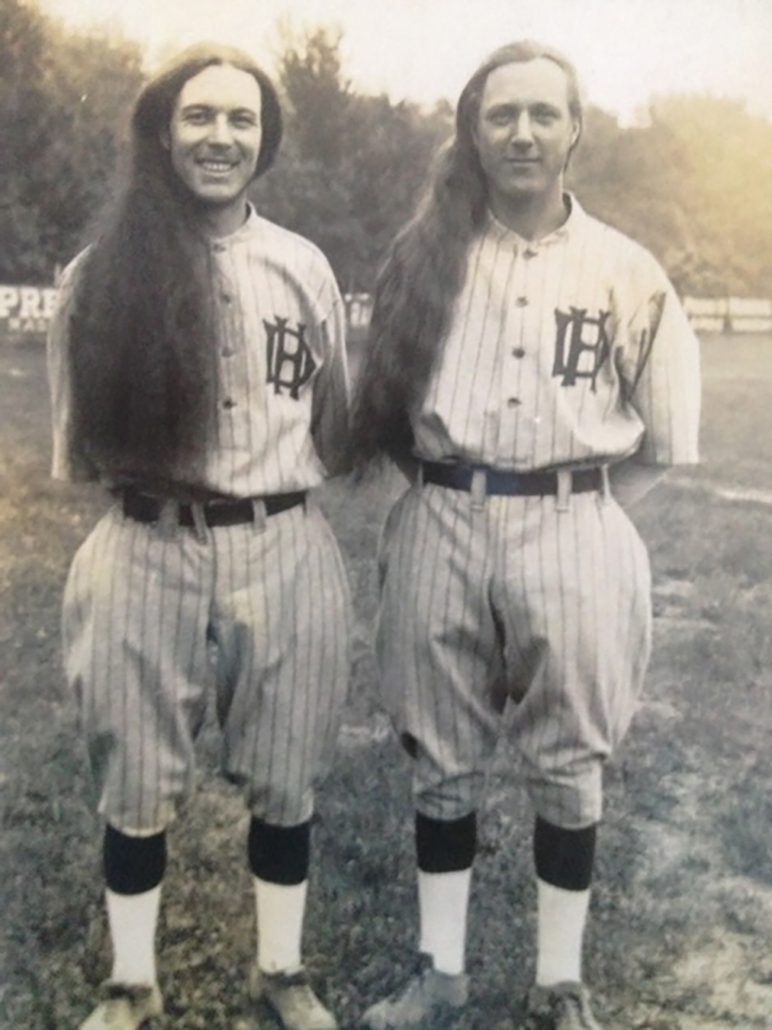

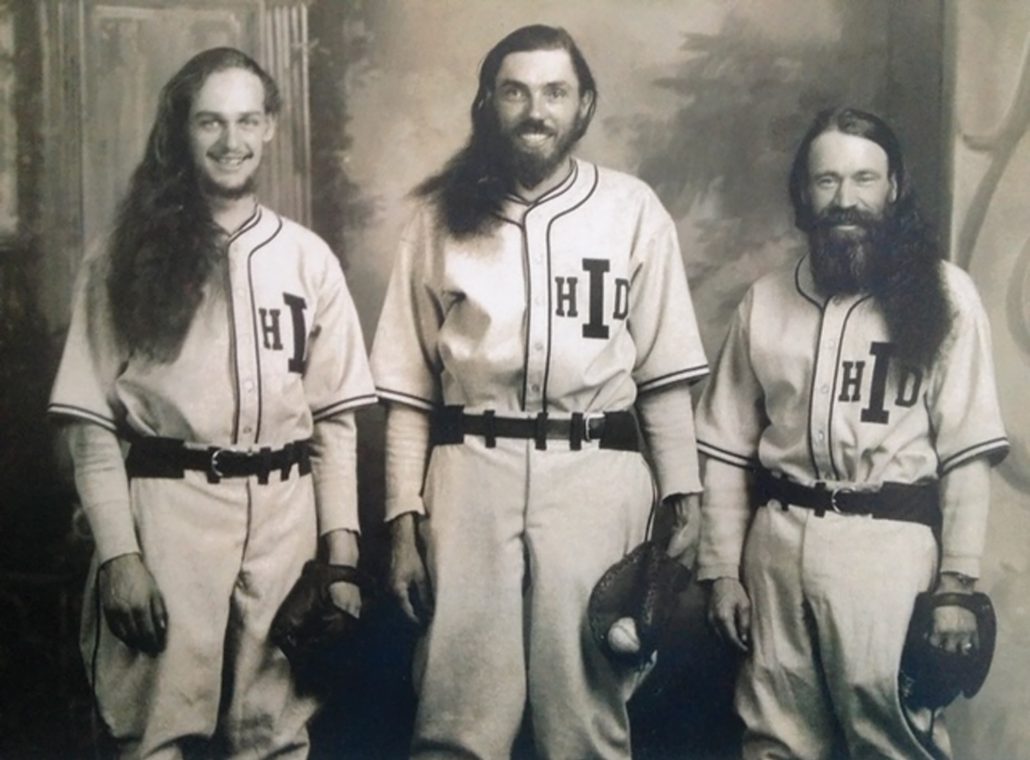

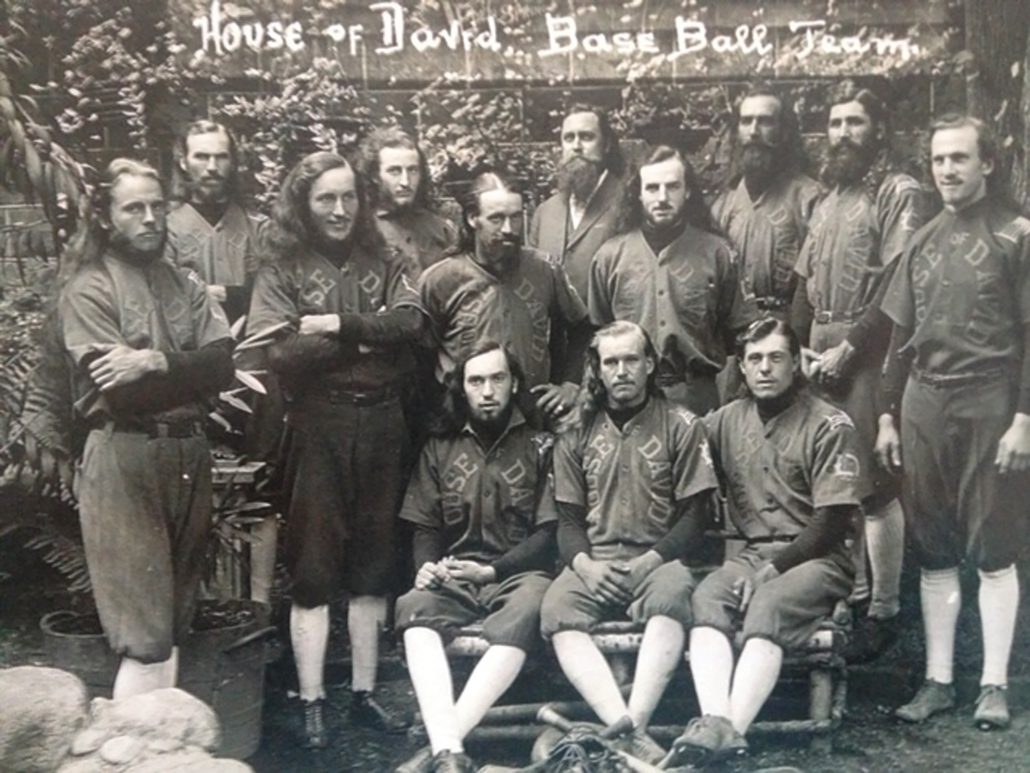

The turn of the century was a breeding ground for very different varieties of the Christian religion. A charismatic leader, Benjamin Purnell, and his wife, Mary, moved to Benton Harbor, down near the Michigan-Indiana border, where they bought 1,000 acres of land and, in 1903, established the Israelite House of David, an Adventist group. The men all had long hair and beards, following the Bible verse, Leviticus 19:27, “You shall not round off the hair on your temples or mar the edges of your beard.” They also banned alcohol, sex, and eating meat. It was a very strict regime.

Men lived in one building and women in another. Married couples were separated. Women were allowed to vote and hold office, which is especially interesting given that women were not able to vote in the United States as a whole until 1920. No one was allowed to fight in wars. They grew their own food, harvesting fruit and cultivating grain to eat.

Adherents had to give up all of their possessions to Purnell, who used the money to build very nice dwellings, a zoo, a hospital, and an amusement park. They had their own restaurant and hotel, The Eden Springs Resort, that was quite famous. They had their own electricity plant, a tailor, a carpenter, and a laundry. Tourists came over from Chicago on a regular boat, then took the trolley to the House of David attractions. The organization boasted more than 1,000 people at its peak.

Despite their austerities, they did like to have fun. Two organizations grew out of the group that emphasized the “fun” part and attracted new members.

Bands with 20 members were created, and they played the vaudeville circuits in bright red uniforms from 1906 to 1927. They were well known and liked when they arrived at the small towns with theatres. They passed out tracts about their group to the audiences. They saw music as a part of religious services and for their own entertainment, as well. No one was left out: men’s bands, women’s bands, and even children’s bands gathered together and played in enjoyment.

The other “fun” organization was a baseball league. They taught that baseball disciplined the body, mind, and soul. They had three teams that toured the Midwest and the East Coast, eventually in the amateur leagues, playing semi-pro teams, and, according to Wikipedia, the House of David played several games in Kansas City against the Negro League, made famous by Satchel Paige.

The House of David teams featured aggressive base running, skillful fielding, and dexterity at bat. But they also had fun—they have been compared to the Harlem Globetrotters, using their talents to create entertainment for the audience. For instance, they were known to hide the baseball in their beards, and sometimes the outfielders rode around on donkeys, among other tricks.

In 1908, two groups moved up from Benton Harbor to Aral: a men’s group lived in the former lumbermen’s boarding house on the south side of the river, and a women’s group in the boarding house on the north side of the river.

The community rebuilt the mill and began manufacturing railway ties, shingles, fence posts, telegraph poles, and other necessary items. They farmed the land and cooked great vegetarian dishes. They worked hard—farming, and lumbering—but they played hard, too.

The men helped to expand baseball in Northern Michigan: a few towns like Frankfort had unofficial baseball teams already, playing on someone’s farmland, and the House of David teams were happy to play them.

They also had their own schooner, The Rising Sun, which they sailed up and down the Lake Michigan coast at sunset, while dressed in their bright red band uniforms and playing their brass instruments for their own enjoyment and the pleasure of those on the shore.

By 1911, the Otter Creek forest was depleted, and it was difficult to find wood to process for smaller items, like railway ties and shingles. So, the House of David members tore down the mill and sold the lumber, moving back to Benton Harbor. By 1922, even the Bancrofts had left Aral—now a ghost town.

In 1927, scandal reared its ugly head: Benjamin Purnell was charged with assaulting several young women and with embezzlement. He died before the trial was completed.

One can still see the House of David Museum—along with the remains of the hotel and restaurant—in Benton Harbor, but we can only see the ghosts of the ballplayers, warming up for a game in Aral, Michigan.

P. G. Misty Sheehan is a retired professor of humanities at Chicago’s College of Dupage and former executive director of the Benzie Area Historical Society and Museum.

In the woods just off the parking lot at Esch Road beach, there is a historical marker with a few photos that describes some of the history of Aral. Local writer Ann-Marie Oomen’s 1998 play Aral: A Folk Opera recreates a double-murder shoot-out, not mentioned in this article, and the waning days of Aral’s lumber boom. The following books also recount the story of Aral: Ghost Towns of Michigan, Volume I by Larry Wakefield; Ghost Towns, a publication of Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes; 100 Years in Leelanau by Edmund M. Littell; and The Logging Era: Period of Graft and Exploitation by Dave Warner.

SIDEBAR

Michigan’s Lumber History

During the second half of the 19th century, Michigan was the nation’s leading lumber producer.

By 1850, the United States was in a predicament. Rich in vast tracts of land, there was little cash reserve to pay debts. The federal government sought to alleviate the situation through the Swamp Land Act, which ceded unusable land due to swamps—even marshes or intermittent ponds—to state governments, allowing them to sell the land to speculators who wanted to establish commerce for as little as $0.75 to $1.50 per acre.

And so the timber rush began. Lumber barons, who had already seen the forests depleted in eastern states such as Maine, began to battle for Michigan’s and Wisconsin’s land. What property could not be purchased legally was acquired through more nefarious means.

For instance, the Homestead Act of 1862, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, allowed any homesteader who was at least 21 years of age and not in trouble with the government to lay claim to 160 acres of land, as long as he developed the property; the lumber barons were not above hiring bogus homesteaders to claim their plot and stay until the land’s timber was cut.

All of this wooding excitement revolved primarily upon Michigan’s white pine, which was used to build houses, barns, fences, buggies, and more. Nicknamed “cork,” it was an ideal source of lumber, because it grew straight and tall, with the oldest specimens 200 to 300 years of age, 200 feet tall, and up to eight feet in diameter. When felled, the pine logs were buoyant, making them easy to float down the river to the sawmill, and they yielded more usable lumber per acre than other soft woods.

A $1.50 purchase of land could bring in more than $75 of lumber, which was a lot of money in those days.

Numerous logging settlements built up in Michigan during the mid-1800s, with “shanty boys” (lumberjacks) hired to work camps for $1.50 to $2 pay for a 14-hour day. Much of the labor was done during the winter, because the logs were easily hauled to the banks of the frozen rivers by horse-drawn sleds. They were held until the spring thaw, then floated downriver to retention ponds and lifted up to sawmills for processing.

For many, the job—which entailed backbreaking work and nights in a bunkhouse, strewn with other sweaty, lice-infested men—was a means to earn enough money to establish a farm of their own

Excerpted from “Shoot-out in the Ghost Town of Aral,” a July 2015 article by Linda Beaty that published in both the Glen Arbor Sun and The Betsie Current.