A Polar Bear Returned to Russia

By Andy Bolander

Current Contributor

As 4th of July celebrations for our country’s Independence Day approach, it seems timely to recall that 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of U.S. involvement in World War I. Notably, there was a unit with very strong ties to this area that was fighting the Bolsheviks in Russia until May of 1919, six months after the armistice, and theirs is an interesting—and little-known—history.

One of the men in the 339th Infantry—which referred to themselves as the “Polar Bears,” because the Russian winters were so cold—was named Walter Dundon, born in Elk Rapids and raised in Elberta. His mother ran a bakery and restaurant across the street from the Elberta waterfront. (The building was located in the park across the street from The Cabbage Shed, next to the pump house building. It was replaced by the Veterans Hall that was built in 1946, which is also now gone.) The backroom of Dundon’s Bakery was a place where river drivers would sleep after driving logs down the Betsie River.

Dundon first joined the U.S. Army in 1911 and was stationed in Alaska. After his discharge, he worked for the Ann Arbor Railroad as a brakeman in 1914. Then he was drafted in 1918, while living in Detroit, and married his wife, Cecile Hager, before he went to Camp Custer in Battle Creek. In September 1918, he landed with the 339th Infantry forces in North Russia.

The experiences of the American North Russian Expeditionary Force during World War I are often overlooked.

The Americans were involved in the North Russia theater of operations, which was a convoluted diplomatic mess of Allied relations, Russian social reform, and unpaid debts. Their military purpose was to maintain an Allied presence on the eastern front of the European conflict. After the Bolshevik Revolution on November 7, 1917, the Allies were weakened by the loss of Tsarist Russia. The Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany in March of 1918, and the line of battle on Germany’s eastern border disappeared. So the American North Russian Expeditionary Force appeared in Archangel, Russia, in September 1918 to keep the Bolsheviks in the south and the Germans out of Murmansk—this adventure later became commonly known as the Polar Bear Expedition.

The units arrived in Archangel, Russia, on September 5, 1918, and 175 out of more than 5,000 troops in the 339th Infantry were unable to disembark their troop transports, as they were being quarantined with the Spanish flu. Although the Americans were specified not to be an offensive force, a day after arrival, on September 6, the British command ordered a push southward along the railroad to Vologda.

It was hailed as a victory, but it had created a front of 450 miles in length that the Allied Forces struggled to defend for the next nine months. (By contrast, the front between France and Germany was roughly the same length, about 500 miles long, and had millions of soldiers trenched in on either side, whereas the Americans, who comprised the majority of the boots on the ground who were covering the area outside of the Russian city of Archangel, numbered only 5,500 men.)

The notorious Russian winter battled the American troops. President Woodrow Wilson determined that the American soldiers in Russia would not be equipped with standard Army kits—no American flags were to be officially brought to Archangel, and the soldiers did not wear the uniform of the U.S. Army. Cold weather gear, provided by the British Army, was criminally inadequate. Soldiers bartered for improvements from the markets or looted the dead for fur-lined hats, gloves, boots, and coats, which were suitable for the environment that they had been commanded into.

Local Connection

Walter Dundon of Elberta was a Sergeant in Company “M” of the 339th Infantry, and despite this small sample of the trials that he and his companions experienced, he would willingly return to the same frozen countryside a decade later.

During the early period of WWI, Dundon was awarded the Cross of St. George—a Russian award—for his heroism, and he was promoted to 1st Sergeant. He exhibited excellent leadership during this time, and he continued to be in a leadership role after the war ended, as part of the Polar Bear Association, which was a veterans organization for those soldiers who had served in Russia during the First World War.

In 1922, Governor Green of Michigan appointed a commission to locate and retrieve fallen American soldiers that remained in Russian soil when the U.S. troops were withdrawn. Gordon T. Shilson, a native of Traverse City, was appointed as the commission’s chairman. Dundon, who was then serving as president of the Polar Bear Association, was included in the commission, as well.

By July 1929, enough research and fundraising had been accomplished to send a team over to Russia and retrieve the fallen American soldiers. In partnership with the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the U.S. Government’s Graves Registration Service, Dundon had an adventuresome time when he returned to Russia, and the group retrieved 84 American bodies. All of these service members were identified, except two, who were only identified as American by their uniforms.

The Polar Bear Association dedicated the Polar Bear Monument at White Chapel Cemetery in Troy , Michigan, on Memorial Day of 1930, and a total of 55 of the total 84 bodies from the Russian soil were interred in American soil at that location. (When the bodies were retrieved, the bereaved families had an option to be buried with the Polar Bears or a standard burial near the family’s home, so some of the retrieved bodies were buried elsewhere.)

Dundon worked as a civil servant in Detroit and Lansing, later moving to Frankfort by1964, where he lived until his death on January 3, 1970. He is buried at the Crystal Lake North Cemetery, which is north of Frankfort on M-22, just past Crystal Gardens and before the Congregational Summer Assembly (CSA).

As a veteran, I am impressed with the accomplishments of the Polar Bear Commission, and, moreover, of the foresight and the awareness to take detailed notes where each death or burial took place in Russia in 1918. They did this because they knew that they would one day return to retrieve their fallen comrades, and they followed up on that commitment a decade later. I would like to think that the same would have been done for me, if I had fallen during my service (in the Navy, on the Indian Ocean after 9/11). The efforts of the Polar Bears make me proud to be an American veteran, and theirs is a great history that should be better known.

Andy Bolander is a volunteer with the Benzie Area Historical Museum, which will conduct a cemetery tour on Tuesday, July 11, from 7-8 p.m. A remembrance ceremony will be held at Walter Dundon’s grave that evening. Starting Memorial Day weekend, the museum has been maintaining a display on the Polar Bears as part of the World War I exhibit that will be open for the duration of this summer. Check it out during museum hours: Tuesday through Sunday from 1-5 p.m. Or call 231-882-5539 if you have questions. Visit the museum online at BenzieMuseum.org.

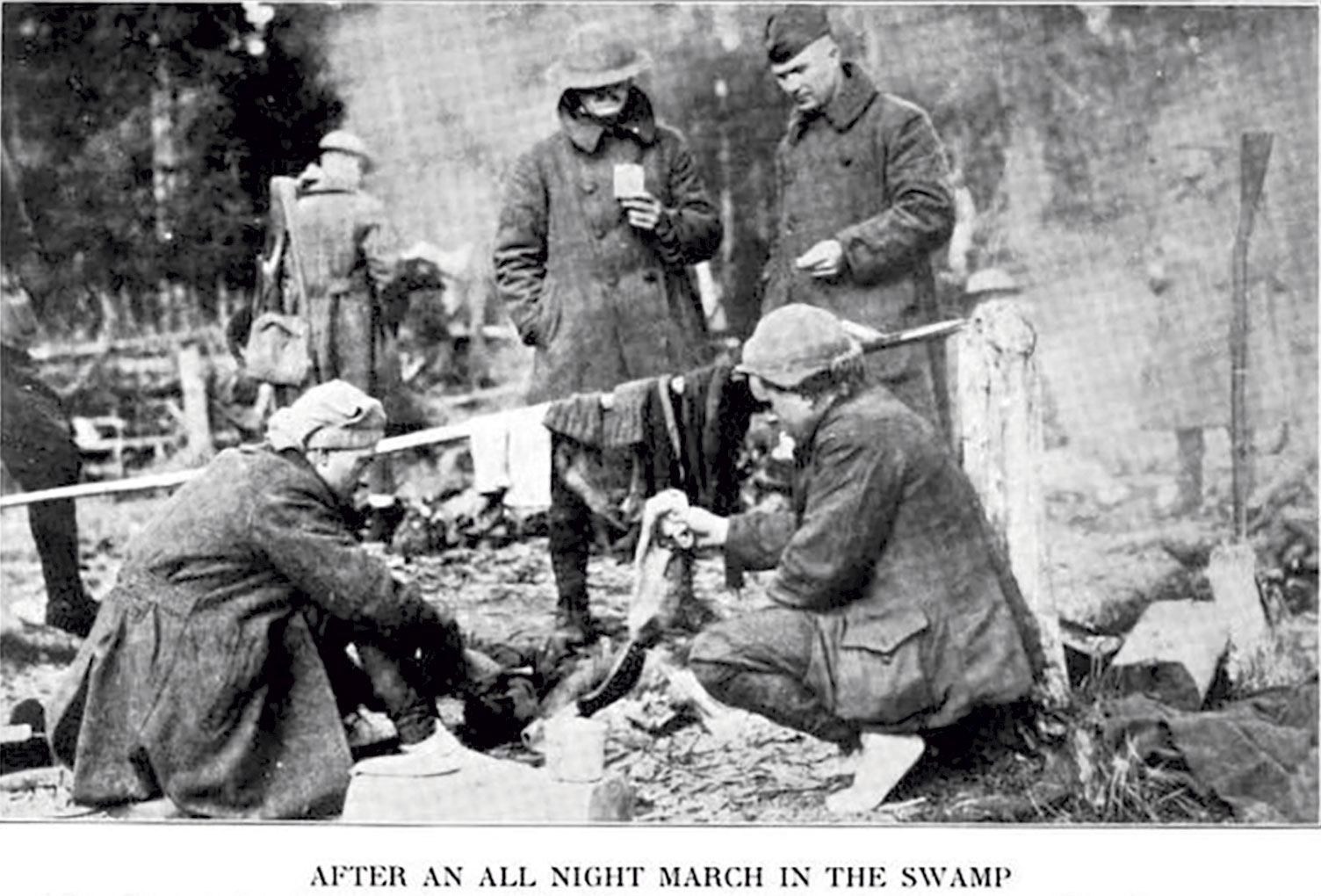

Photo Caption: Born in Elk Rapids and raised in Elberta, 1st Sergeant Walter Dundon (back right) of “M” Company, 339th Infantry, stands next to a campfire, made to dry socks after a 17-hour trek in the woods of Obozerskaya, Russia, on September 29, 1918. The 339th Infantry referred to themselves as “Polar Bears,” because the Russian winters were so cold. Photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library.