From charcoal to road surface

By Andrew Bolander

Current Contributor

They say that there are five seasons in Michigan: fall, winter, spring, summer, and road construction.

Yet reminders of the lifetimes that preceded our own modern timeline are everywhere—crumbling foundations of long-gone buildings, overgrown paths, and giant old lilac bushes hint at the events of the past. Running through the center of Benzie County, Cinder Road is another of these reminders, and the story behind the naming of Cinder Road reaches back to World War I.

Even before that, in 1895, the Chicago & West Michigan Railroad—later known as the Pere Marquette Railroad in 1899—opened a spur from a point named Clary to Honor. This opened up a section of Benzie County to industry.

For instance, a burgeoning industry was charcoal, created from the burning of wood in a low-oxygen environment. The wood in local charcoal kilns was cordwood—beech, birch, and maple were the preferred sources for charcoal. Branches, stumps, and just about anything that was not a log would be used as cordwood, as long as it fit the desired dimensions of the kilns that would burn the wood. Cordwood was about eight inches in diameter and four feet in length; the dimensions were important, in order to have the kiln’s load burn evenly. Occasionally an ember remained in the center of the charcoal, and the workers would take the ember and put it in their fire at home.

One early pioneer in this industry was the Desmond Chemical Company—named after owner Frank C. Desmond, a graduate of the University of Michigan—which built its first charcoal kilns just three years after the railroad expansion, in 1898, adjacent to the new track of the Pere Marquette Railroad, just west of the crossing of Pioneer Road, over the Platte River, near Honor.

The domed kilns were built of brick and washed with lime to be airtight. (Notably: In Benzie County, kilns had previously been present at the iron works in Elberta, south of Thompsonville, and in Wallin, now a “ghost town.”) Cordwood was brought to the kilns by wood-choppers.

near Thompsonville Highway (also known as County Road 669), and this secondary operation became a community called Carter’s Siding. However, the new “retort kilns” at Carter’s Siding were of a different design; retort kilns had doors, and a buggy—loaded with cordwood—would be wheeled into the kiln on rails, providing for a faster time loading and unloading the kiln. In this photo, four men stand in front of the buggy, loaded with cordwood. Image courtesy of the Benzie Area Historical Society.

Many of the workers at the Platte River kilns were Native American; they maintained a Methodist Sunday School near the kilns, and locals praised the quality of the singing, though the hymns were recited in Anishinaabemowin rather than English.

By 1907, construction of new kilns and a distillation plant was completed north of Carter Creek, near Thompsonville Highway (also known as County Road 669), and this secondary operation became a community called Carter’s Siding.

However, the new retort kilns at Carter’s Siding were of a different design from Desmond’s Platte River kilns; retort kilns had doors, and a buggy—loaded with cordwood—would be wheeled into the kiln on rails, providing for a faster time loading and unloading the kiln. It would take 24 to 36 hours for the load to burn.

Another development was that the exhaust was captured and sent to a distillation plant; wood alcohol and acetate of lime were drawn from the kiln exhaust.

loads of cordwood on sleds over icy roads; transporting cordwood during the winter provided convenient employment for farmers and their teams of horses During the warmer months, wood would be stacked near the location where it was cut, and then it would later be transported during the winter. Wood-choppers traveled as far as Honor, Lake Ann, Bendon, Turtle Lake, and Homestead, around a 10-mile radius. Newspaper advertisements at the time called for wood-choppers, who would be paid $1.15 per cord, or horse teams–like the one pictured here–would be paid $8 per day, with free stabling. Image courtesy of the Benzie Area Historical Society.

The charcoal produced at the Carter Siding and Platte River kilns was sent by rail on the Pere Marquette to the J. C. Ford iron furnace in Fruitport, down near Muskegon. The charcoal was primarily used in cold-blast iron furnaces. Fruitport is the location I know for sure charcoal was sent to. Elk Rapids had a furnace as well. I think most of the usefulness of charcoal was due to its availability. If you wanted coal it would have to be transported in from the Appalachian Mountains. Wood alcohol and acetate were the distillates which were used in making gunpowder.

Winter was the busy season at the woodyard, because it was more efficient to transport the loads of cordwood on sleds over icy roads; transporting cordwood during the winter provided convenient employment for farmers and their teams of horses. In fact, during the warmer months, wood would be stacked near the location where it was cut, and then it would later be transported during the winter. Wood-choppers traveled as far as Honor, Lake Ann, Bendon, Turtle Lake, and Homestead, around a 10-mile radius. Newspaper advertisements at the time called for wood-choppers, who would be paid $1.15 per cord, or horse teams would be paid $8 per day, with free stabling.

In 1912, a group from Detroit purchased the chemical company from Desmond, though the company name was not changed. Thomas Berry—of the Berry Brothers Varnish Company in Detroit—was its president. George Brusie took over as the Benzie County plant’s superintendent.

An example of the plant’s output from 1912: 750,00 bushels of charcoal; 150,000 gallons of wood alcohol; 2.7 million pounds of acetate of lime.

Meanwhile, Carter’s Siding peaked in 1918 with 100 plant employees, 52 teams hauling wood, and an unknown number of wood-choppers.

Demand for fuel caused the Desmond Chemical Company to invest in other modes of transportation, besides the horse teams and sleds. The company bought a Duplex brand truck in 1920 and used it at a number of sites. Another investment was made in a device called the Steam Hauler, which pulled sleds on iced trails and used treads on its drive wheels, with skis at its front; it would pull up to four sleds with a crew of three—an engineer, a fireman, and a man steering the skis up front.

But by 1920, the supply of cordwood in Benzie County became unprofitable to harvest, and the chemical plant closed down. The copper from the distillation plant was transported to Manistique, in the Upper Peninsula, and a chemical plant—known as the Thomas Berry Chemical Plant—was built at that location. George Brusie moved to Manistique to be the superintendent of the new plant, as he had been here in Benzie County for the previous eight years.

The Pere Marquette Railroad spur to Honor was closed around this time.

So how does all of this relate to the naming of Cinder Road?

Well, as mentioned, Carter’s Siding was a community that was centered around the chemical plant, as well as the hotel and the company store, which were both owned by the chemical company. There was also a school, which was a mile north of the plant, at the intersection of Thompsonville and Brownell roads. The tar-papered houses flanked the road up to the school.

Judge Berga Lindy was the keeper of the store from 1915 until the store closed in 1920. He traded with local farmers and stocked the store well—there was a surplus of eggs during World War I (1914-1918), and Judge Lindy always had a supply of sugar, though he had to follow the sugar rations.

The hotel was akin to a boarding house that provided lodging to bachelor employees at the plant. Hugh Rankin ran the two-story hotel, which had about 20 rooms and a dining area.

Carter’s Siding flourished during World War I, because it produced some of the ingredients needed to make gunpowder. The community was well known for its lively dances and a talented baseball team. Guthrie’s Hall was a popular place, at the corner of Thompsonville Highway and what would later come to be known as Cinder Road.

In February of 1918, cinders left over from the charcoal kilns at Carter’s Siding were used to surface what would later be called Cinder Road, in a stretch from its intersections with Thompsonville and Pioneer roads.

So whatever became of Carter’s Siding after the chemical plant was closed, two years later? Well, when the chemical plant was disassembled and the copper-distillation components were moved to Manistique, the thriving community quickly disbanded.

Now, there is nothing but a few foundations left and a couple of flowing wells on private land that give us clues of what was once there.

But the name of Cinder Road—made from literal cinders in the charcoal-making process—continues, as part of the living history of Benzie County.

Andrew Bolander is a volunteer with the Benzie Area Historical Society and Museum. The Benzie Area Historical Museum is open Tuesdays through Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. See upcoming events at BenzieMuseum.org and the continually updating catalog at BenzieMuseum.CatalogAccess.com/home online.

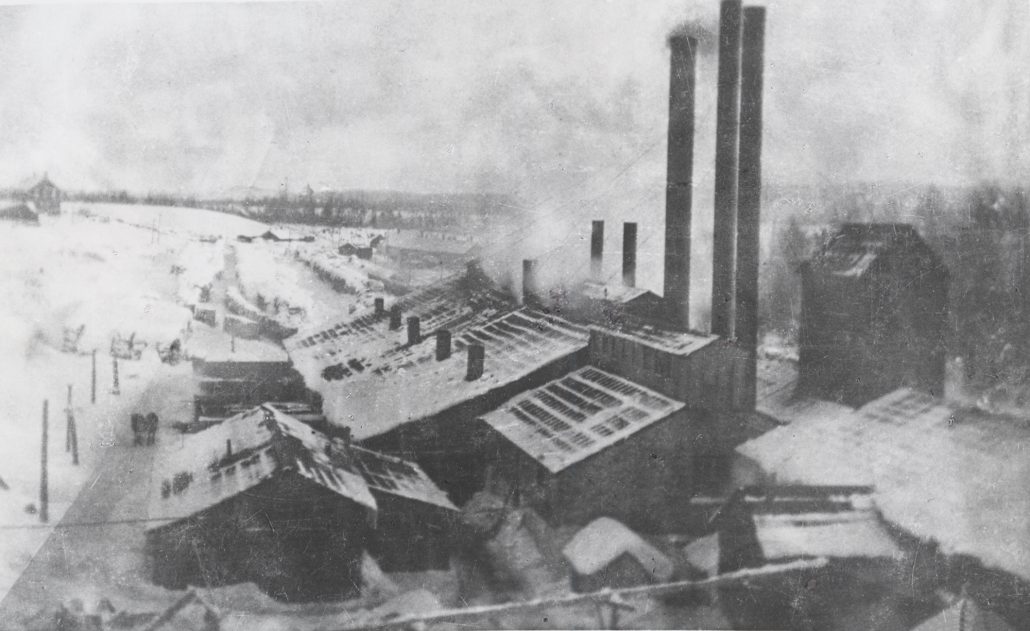

Featured Photo Caption: Workers making charcoal at the Desmond Chemical Plant at the turn of the 20th century in Benzie County. “It was pretty dirty work; it was black,” Claude Carrier said many years later, in an interview on August 4, 1965. “It was good healthy work, though. You know, [charcoal] dirt is good for ya,and doesn’t affect ya much. It’s nothing like other heavy dusts. It’s real light dust. It doesn’t affect ya; only ya get awful black and dirty.”

Hello,

I really enjoyed your article about how Cinder Rd. got it’s name. I had read something similar years ago but then searched and couldn’t find anything for the longest time, so I was really glad to see this.

I’m curious if you have any information on Carters Corners or Guthrie’s Hall? I own the house on the corner of Cinder and 669 that is been in my family since the early ’80’s.

Thank you,

Karl Maurer