Health Department faces federal funding cuts and low measles vaccination rates

By Jacob Wheeler

Current Contributor

The Benzie-Leelanau District Health Department (BLDHD) learned on April 1 that it would face a funding shortfall of more than $230,000 for the remainder of the current 2024-25 fiscal year—much of it related to health services that the department provides to local schools through the MI Safer Schools grant. Moreover, BLDHD will be short $470,000 to support schools in the upcoming 2025-26 school year.

The funding cut from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was no April Fool’s Day joke. Typically, these MI Safer Schools funds are passed from the federal HHS to the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services (MDHHS), which then distributes the money to local health departments—but that will dry up by next month, in June.

In Leelanau County, the BLDHD has a nurse at Northport Public School, thanks to the MI Safer Schools federal funding.

In Benzie County, the Health Department provides school nursing services via the MI Safer Schools grant at Betsie Valley and Lake Ann elementaries within Benzie County Central Schools. (Additionally, Benzie has a School Wellness Program—funded by the state—that provides a BLDHD nurse and social worker for the middle and high schools, along with Homestead Hills Elementary. Frankfort-Elberta Area Schools has a similar state-funded program that includes one BLDHD nurse and one mental health provider who work at both the elementary and the middle/high school buildings. There is also a nurse and social worker at both Leland Public School and Suttons Bay Public Schools, through the same state-funded School Wellness Program. However, because these positions are all funded by the state, they are not subject to the federal cuts, like the MI Safer Schools programs at Northport and the two Benzie elementary schools.)

The Health Department also has nurses available to provide consultation to all schools about topics including immunizations or managing infectious diseases.

Schools in our two-county region have benefited from BLDHD support, particularly since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020—Health Department staff advised schools on how to help children that were sick and how long to keep them home. In some cases, BLDHD supplied a nurse to help deal with everything from stomach aches and headaches to chronic and infectious diseases.

“It’s unfortunate, because [the federal grant] was a very popular program,” says Dan Thorell, who took the job as BLDHD’s full-time health officer in November 2024, after serving since 2022 as the health officer for the Health Department of Northwest Michigan, which was a shared position that included at BLDHD, meaning he spent a day in each county. (This role was previously held by Lisa Peacock.) Now he is full time in just our two counties, instead oft splitting his time elsewhere in the region. “Many schools didn’t have nurses. A lot of that work fell to teachers or office assistants. The result was that they didn’t have time to deal with these things.”

The Health Department has made adjustments in order to continue helping schools through this 2024-2025 school year, but the federal funds will run out by the end of June, Thorell told the Glen Arbor Sun in early April. The BLDHD also will not hire for a couple of vacant positions that he was hoping to fill.

“Cutting this funding diminishes our capacity. Public health infrastructure is being pulled back, and that’s detrimental to our ability to react to outbreaks. We’ll simply have to do more with less,” Thorell adds. “When COVID hit, our public health infrastructure was already underfunded. Now, it’s taking a step backward again. I fear we’ll be back in the position we were in 2019.”

In Northport, superintendent Neil Wetherbee confirmed that the BLDHD places a part-time nurse in the school approximately two days per week. Since Northport Public School does not currently have its own nurse, the Health Department funding cuts may force the school to spend money from its own budget on health services in the future.

“We find significant value in the work a nurse does, so we intend to maintain the services,” Wetherbee says. “This means that $20,000 to $30,000 that should be going to teachers, field trips, pencils, etc.—the learning—will now be diverted to cover this new cost.”

Meanwhile, Amiee Erfourth, superintendent of Benzie County Central Schools, says that the federal funding allows BLDHD to supply a nurse that is shared between Betsie Valley and Lake Ann elementary schools.

“They each get two days a week, and that program’s funding has been cut,” she says. “We are looking for ways we might be able to [continue to] fund this program, as it is very valuable.”

At Suttons Bay, superintendent and early childhood program director Casey Petz says that he is not aware of many public schools that have available dollars to commit to non-essential instructional supports for education. Fortunately, Suttons Bay has their partnership with BLDHD funded through the state program, not the federal funds which are expiring soon.

“BLDHD is a fantastic partner for [Suttons Bay Public Schools]. They are the health organization/provider that operates our clinic inside the school system. This clinic provides students the opportunity to see a nurse and/or social worker while on campus, if needed,” Petz says. “We are a school system, not a health and wellness organization, so it is incredibly helpful for us to have health/wellness providers as partners—they can focus on what they do best, and we can do the same.”

Glen Lake Community Schools, which employs two part-time nurses out of its own budget, nevertheless receives support from BLDHD during outbreaks, including COVID.

“[The Health Department has] this year provided pre-emptive education on measles and what it might look like if we were to have a case at the school,” says Glen Lake nurse Ashley Karczewski. “We have also, at times, partnered with them to provide vaccine clinics at the school.”

Low Measles Vaccination Rates

The Benzie-Leelanau District Health Department has also worked this spring to address relatively low child vaccination rates against measles in this region.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—an agency that is housed within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—children typically receive the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine first when they are between 12 and 15 months of age; the second dose is generally administered between four and six years of age, though the second dose can be administered earlier, as long as it comes at least 28 days after the first dose. There are special circumstances, of course: for instance, in the case of international travel, infants between six and 11 months should receive one MMR dose before departure. Additionally, during outbreaks, health departments might advise an early dose for infants in this same age range, an earlier second dose for children between one and four years old, and a booster for adults.

In March 2025, Michigan’s MMR vaccination coverage for children between 19 to 35 months of age was 79.4 percent, according to the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services, which is down from 85 percent in March 2020. Some places are experiencing steeper drops than others.

According to data compiled by Bridge Michigan from the fourth quarter of 2024, only six counties statewide have a childhood measles vaccination rate above 85 percent, and the rate is less than 70 percent in eight counties.

Generally, a community vaccination rate of at least 95 percent is recommended to achieve “herd immunity” and effectively prevent measles outbreaks.

As of late April, in Leelanau County, 82 percent of children between ages six to 18 years old have received the MMR vaccine, which offers 97 percent protection after the second dose. In Benzie County, the number is 83 percent.

“That rate is relatively low. Ideally, we should be at 95 percent,” Thorell explains. “Very few vaccines are as effective as the measles vaccine.”

With measles outbreaks mounting nationwide and Michigan confirming its first cases since 2019—as of late April, nine confirmed cases in five counties, including as far north as Grand Rapids—the BLDHD has taken proactive steps to encourage vaccines and prepare for potential cases in Benzie and Leelanau counties.

BLDHD has worked with local school administrators to provide information on measles and prevention strategies. Shortly after spring break, the Health Department provided a letter with general information about measles and vaccine availability to all schools, so that they could send to parents through their communication networks.

The department also hosted vaccination clinics in early April, at both its offices in Benzie and Leelanau counties, which meant giving another 16 MMR doses. The measles vaccine is also available through one’s physician.

“I estimate there are about 300 to 350 school-aged children in Benzie and Leelanau counties who are not fully vaccinated,” says Michelle Klein, the BLDHD director of personal health. “I’ve seen how miserable measles can make you, and I hope to see as many of those kids protected as possible.”

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases, spreading through airborne droplets that can linger for up to two hours after an infected person has left a room. Nine out of 10 unvaccinated individuals exposed to the virus will become infected.

Beyond the initial infection, there can be long-term complications associated with measles, including immune system damage, respiratory problems, and a rare, potentially fatal brain disease called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE).

The vaccine—in use since the early 1960s—has been proven safe and effective through millions of doses administered worldwide.

Measles was declared “eliminated” in the United States in 2000—which was widely credited to an ambitious vaccination program.

But an anti-vaccine movement, buoyed by “COVID-19 fatigue,” has allowed measles to return as a threat.

Much of the movement can be attributed to a 1998 study that alleged a link between MMR vaccines and autism, though that study has been widely debunked.

Notably, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.—who serves as the Trump administration’s HHS secretary—has previously questioned the scientific consensus that vaccines do not cause autism, though he recently endorsed the MMR vaccine during the current U.S. measles outbreaks, drawing criticism from his anti-vaccine supporters. Still, he also promoted “alternative therapies” for measles: antibiotics, inhaled steroids, and vitamin A.

“The MMR vaccine is among the most effective and well-established vaccines available, with a long history of safe use,” adds the BLDHD’s Klein. “While we hope to avoid measles cases in Northern Michigan, maintaining high vaccination rates is essential to protecting the entire community. The MMR vaccine is easily accessible through the health department and most healthcare providers.”

A version of this article first published in the Glen Arbor Sun, a Leelanau County-based semi-sister publication to The Betsie Current. Additional reporting from Emily Votruba of The Elberta Alert.

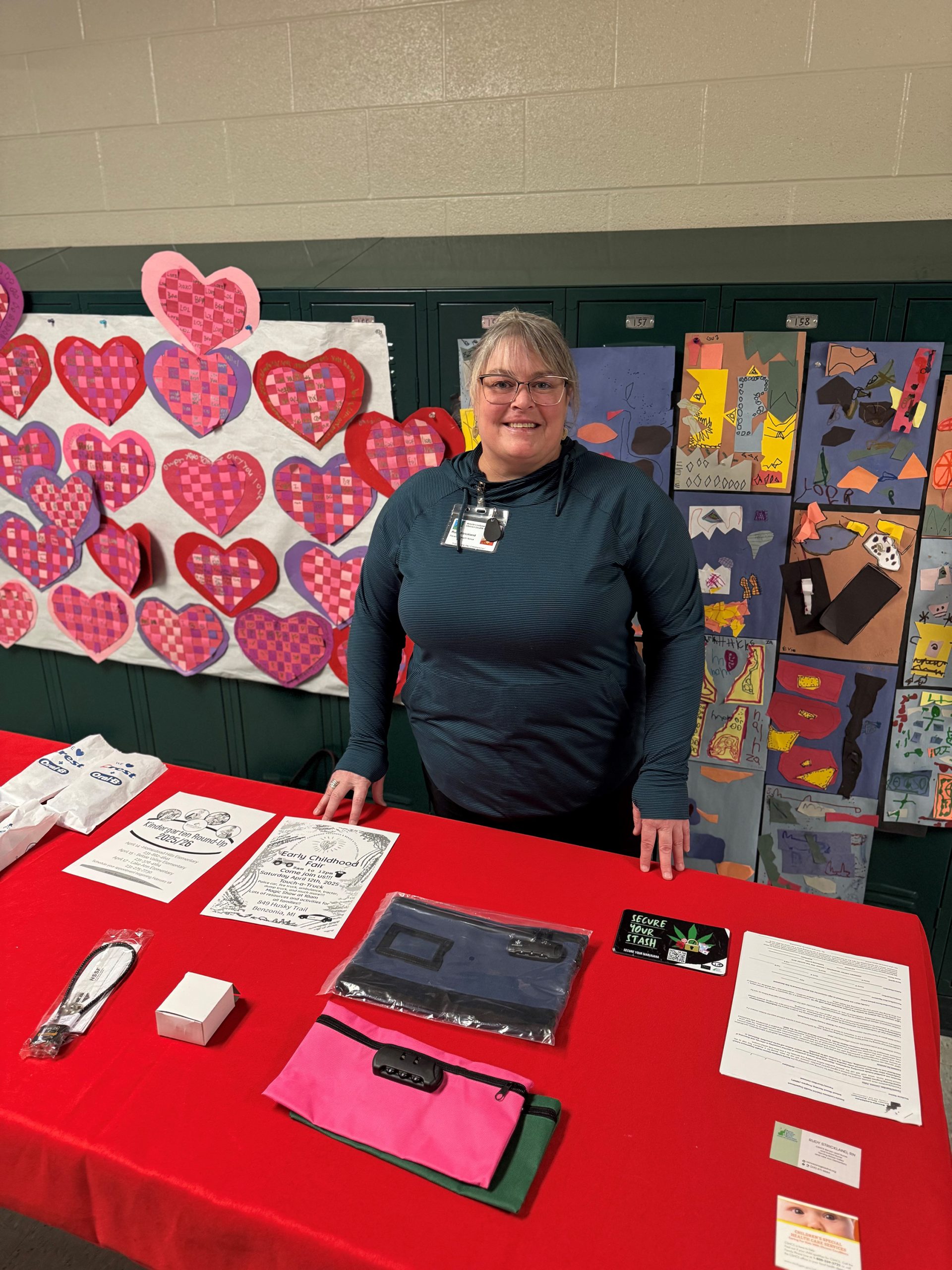

Featured Photo Caption: Rudy Strickland, from the Benzie-Leelanau District Health Department, serves as a school nurse for Betsie Valley and Lake Ann elementary schools within Benzie County Central Schools. Due to funding cuts from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the grant paying for this position was eliminated. The local health department has been able to tap into another funding source for Strickland to continue her work for the remainder of the school year. Pictured at a parent night at Lake Ann Elementary. Photo courtesy of BLDHD.