The tale of a faithful ship and the “Good Will” of a community

By Jed Jewarski

Current Contributor

Editor’s Note: Many of our readers are surprised to hear that we had two years of publication back in 2005-2006. This article is from our 2005 archives, but we really find value in the local history, and we thought that you would, too—whether you are reading this for the first time ever or just for the first time in 14 years.

“If only those weathered old timbers could talk,” people often remark, as they explore the ancient forests, gracefully aging barns, and bleached shipwreck timbers along the shores of Benzie and Leelanau counties.

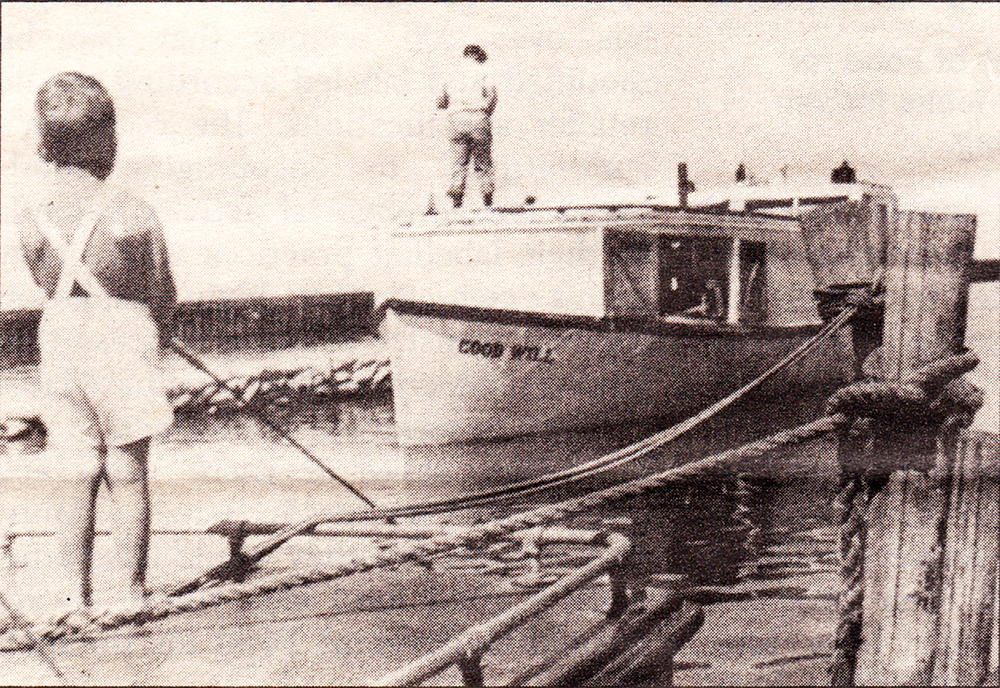

Herein is the tale of an aged boat, sinking into the muddy headwaters of Betsie Bay, a fishing vessel named “Good Will,” which plied the quicksilver out of Leland for 64 years.

It is a tale of the human spirit, of kindness and adversity, of independence and community. It is a tale that reflects the ways of life along our northwest coast.

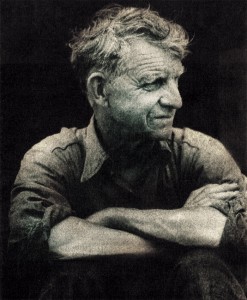

Carlson betrays the rugged life of commercial

fishing on the Great Lakes. Erhardt Peters Collection / Leelanau Historical Museum.

The story begins in the mid-1870s, when a great influx of immigrants arrived to this area of the Great Lakes.

Among the thousands laying their claims here was Nels Carlson and his family. They settled on North Manitou Island and cleared land to begin farming.

Life in the new land was not easy; the soils here were sandy and poor, and people quickly learned to be resourceful. Nels Carlson and his son, Will, soon began fishing on Lake Michigan to help feed the family and to earn extra income. Fishing was apparently more fruitful than farming for the Carlsons, and in 1906, they moved to Leland and established a fishery.

At this time, Leland’s community centered around its modest harbor and fishing fleet. As time passed and maritime commerce became less prevalent, Leland’s fish town became a community within a community—the sailors and fishermen being understanding and sympathetic to the often harsh ways of making a living on and around the water.

The early morning hours of August 1941 saw Will Carlson and his son, Pete, fishing aboard their boat, Diamond, between South Fox and North Manitou Islands.

The Diamond was the Carlsons’ first boat, a 34-foot open boat, similar to the early sailing Mackinaws. Rather than being propelled by sail, the Diamond had a gasoline engine, which allowed fishermen to more reliably travel to and from their nets. These nets were often set many miles from safe harbor around the fertile fishing grounds of the islands.

Fate intervened that day, when a fire broke in the engine of the Diamond.

The flames soon leapt into the oily wood timbers adjacent to the burning engine, and the searing orange flames became a horrific contrast to the cold, dark blue waters that surrounded them.

The fire could not be extinguished, and it became apparent that they were now confronting the unenviable decision of death by fire or by drowning.

Pete Carlson gave the only life jacket to his father, and then he cleverly began stuffing fishnet floats into his own shirt for buoyancy.

Although it was August, the deep waters of the Manitou Passage took their breath away when they jumped overboard. Floating together in the frigid lake, the radiant heat of the flaming Diamond was of little consolation.

Within a short time, the unmerciful effects of cold water took its toll on the elder Carlson—Will soon died of exposure.

In desperation, Pete Carlson began swimming with his father—the life jacket still on his body—toward North Manitou Island, miles away. He was ultimately forced to release his father’s body, as it had become too much of a burden and would clearly imperil his already minute chances of survival.

After nearly a full day of swimming, darkness fell. The night was clear with a bright moon; fighting exhaustion, Pete Carlson swam on.

Meanwhile, in Leland, Percy Guthrie and Manley Cook had gotten the fish tug Irene underway, along with others, to search for the overdue Diamond. Criss-crossing the area between the two islands, they maneuvered the Irene so as to take advantage of the moon illuminating the water.

At 4 a.m., Guthrie and Cook were becoming weary, when a disturbance was seen on the shimmering lake surface—Pete Carlson, now unable to speak, was frantically slapping and splashing the water to attract attention.

The rescuers brought Pete Carlson aboard, and he was near death after being in the water for 20 hours. He soon recovered, and his father’s body was found later, still buoyed by the life vest.

The village of Leland was saddened by the news of the tragedy and rallied to aid the Carlsons. The community wanted to see Pete Carlson be able to maintain his family’s business, so generous people in the village raised a considerable amount of money to help to pay for the building of a new fishing boat.

Big John Johnson of Omena was contracted to build the new gill net tug—35 feet long with a 10-foot beam, it was powered by a universal gas engine.

The new tug was christened Good Will, with the name reflecting the kindness of the town, and in the same context, commemorating Will Carlson.

The Good Will proved itself a fine boat, and it made port in many storms when others failed. When not fishing out of Leland, the Good Will was often seen in Grand Traverse Bay or in Saugatuck.

Pete Carlson and his brother Clarence usually skippered the tug, with Pete’s son Bill learning the trade aboard her.

In 1953, the old universal was pulled, and a three-cylinder GM truck diesel was installed. When the Carlsons had a new 40-foot steel tug built in 1965, and the Good Will was tied up in Leland and converted to a floating antique store.

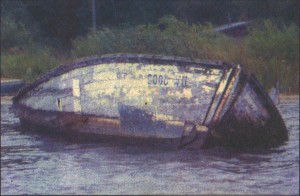

waters of Betsie Bay. Photo by Jed Jaworski.

A year later, a Mr. Bowers of Elberta, while in Leland, took a liking to the old Good Willand purchased it. His intentions were to run it down to Elberta and restore it as a cruiser.

While en route to Betsie Bay, however, a storm kicked up. The Good Will began to take on water, and Bowers was forced to beach the boat at Sleeping Bear near Empire, where it sank—the forlorn Good Will looked but a mere speck along the great reach of sand at Sleeping Bear.

With perseverance, temporary repairs were made, and it was pumped out and refloated.

Having time to reconsider his original intentions with the boat, Bowers pulled the engine and moored the Good Will offshore of his cabin on Betsie Bay. There it soon settled to the bottom, where it has remained for the last 39 years. [Editor’s Note: Reminder that this article was originally written in 2005, so it would actually be 53 years now.] The hull could be viewed from the M-22 bridge, between Frankfort and Elberta, for decades.

Now, the Good Will rests nearly entirely beneath the water and silt of the bay, only its story surfacing within the maritime lore of our area.

Explore our coast and culture: Today, you can visit “Fishtown” and the Carlson Fishery in Leland. Take the ferry to North Manitou Island over the waters that the Diamond plied and now rests beneath. Visit the Leelanau Historical Museum to learn other Fishtown tales, view photos and artifacts, or assist the Fishtown Preservation Society. See a real historic fish tug, like the Good Will, at the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore’s Glen Haven Cannery maritime exhibits. Learn about the Betsie Bay fisheries at the Benzie Area Historical Museum and at the “Waterborne” exhibit aboard the S.S. City of Milwaukee in Manistee.

Want to read more of our 2005-2006 archived stories? Go online to bit.ly/TBC2005 and

bit.ly/TBC2006.

Fascinating story very well done. I’ll link to you on our site. Thank you.

Fascinating

Thanks for uploading this story so we can all learn more about this part of our maritime history.