What can history teach us

By Greta Bolger

Current Contributor

For most of us, unless we are students of history or infectious disease specialists, the 1918 flu pandemic has never seemed very relevant—until now. In the face of the current COVID-19 pandemic, many are looking back at 1918 to find out what lessons were learned, what mistakes were made, and how much difference 100 years of human progress has made in our approach to dealing with a deadly virus.

However, comparing the events of 1918 and 2020 presents a number of challenges.

The world of a century ago was different in myriad ways. Far less was known about infectious diseases. Microscopes of that time could not even detect viruses. Communication channels were far slower and much less seamless than they have become through globalization and the advent of the internet. Though international business and recreational travel were far less common in the early 20th century, World War I troop movement was a major factor in spreading the virus globally. And importantly, records from that time are not wholly reliable, both because of underreporting and lack of connectivity.

Nevertheless, a closer look at the similarities and differences between the 1918 pandemic and the story that is unfolding worldwide right now may provide some insight and guidance as we navigate this once-in-a-century calamity that has so profoundly impacted our lives—even here, in our small, rural Benzie County.

Kansas Army Base to Europe and Beyond

We know with some certainty that COVID-19 started in Wuhan, China, and originated in bats; it is a SARS strain.

Meantime, although the 1918 flu was and still is widely referred to as the “Spanish Flu,” there is no clear consensus of where this H1N1 strain of the flu originated. Many signs point to Camp Funston, an Army Base in Fort Riley, Kansas, where, in March 1918, an outbreak sent as many as 500 soldiers to the hospital within a week.

The initial cases were relatively mild and resolved fairly quickly, and the recovered troops were shipped out with their fellow soldiers and hundreds of thousands of others to the front in Europe. It did not take long for the disease to spread from the U.S. military to the civilian population of Europe, and then around the world.

Wartime Priorities Impact Response

Throughout the spring and summer, the 1918 flu continued to spread and mutate globally, becoming increasingly lethal. This period is known as the “First Wave,” which took between 3 and 5 million lives worldwide.

During this period, the extensive resources committed to the war effort were not available to help battle the virus. Large numbers of nurses were deployed overseas and at military bases in the United States, creating a shortage of medical workers to tend the sick. In addition, treatments were mostly limited to comfort care, as no effective medicines or vaccines were available.

Meanwhile, manufacturing plants continued operating at full steam to provide essential goods and equipment to the military, keeping thousands of workers on the job. And because attention was focused on the war and not on public health, very few protocols were in place to stop the spread of the virus.

Moreover, the fundamental nature of the virus was not well understood, even by medical professionals—for instance, doctors making house calls to private homes increased the potential of transmitting the virus from house to house. Scientists spent precious time and effort trying to find the bacteria that was responsible for the deadly flu, when it was actually a virus. Months went by. Then came the Second Wave.

Second Wave Changes Everything

The Second Wave of the 1918 flu pandemic began in the early fall of that year, culminating in an estimated 30 to 50 million deaths worldwide—more than the total of all military and civilian deaths caused by World War I.

According to a report by the Centers for Disease Control, an estimated 195,000 deaths from the virus occurred in October 1918 alone. The shortage of professional nurses deployed with the military—coupled with the unwillingness to use trained African-American nurses—led to a call by the Red Cross for volunteers to serve in an ad hoc nursing capacity. It was during this time that strict quarantine rules and public safety protocols began to be put in place in many cities around the country, including masks, school and church closures, and vigorous public education programs.

One of the most tragic chapters during the Second Wave occurred in Philadelphia, where a giant parade designed to support the war effort through the sale of Liberty Loan war bonds was held on September 28, 1918, attracting a crowd of 200,000. Within 72 hours, every bed in Philadelphia’s 31 hospitals was full. In the week ending October 5, a total of 2,600 had died; a week later, the death toll rose to 4,500. A virtual shutdown of the city on October 3 did little to allay the skyrocketing casualties.

What Was Happening in Benzie County?

Sources for the specifics of how Benzie County experienced the 1918 flu pandemic are limited and are available primarily from the archives of the Benzie Banner, predecessor to the Benzie County Record Patriot. Since the local paper was a weekly then (as it is now) and a war was on, only a few facts can be gleaned from the late 1918 and early 1919 issues. According to Jane Purkis, volunteer curator at the Benzie Area Historical Museum, these were the sole mentions in the weekly during the height of the pandemic:

- October 3: Flu cancelled the draft for 21 Benzie County men.

- October 10: “Violent cold seems to be epidemic in this community,” wrote a local correspondent.

- October 17: Frankfort physician sees 16 cases of the flu while making his rounds. Both 4th and 6th grade teachers have the flu. Benzonia schools closed until October 28.

- October 20: All Congregational churches closed.

- January 2: Wallin schools closed for two weeks.

- January 23: Honor schools closed, citing intensity of epidemic over the last 10 days.

Considering that this was a small community weekly in a rural area with a lower population, the response to the virus seems reasonable, particularly when you compare the year-to-year statistics for deaths in both Michigan and Benzie County.

Why “Spanish” Flu?

Many people incorrectly assume that the 1918 flu pandemic was dubbed the “Spanish flu,” because it originated there, but that is not the case.During World War I, the countries that were participating in the war were censoring news of the flu, in order to keep up morale. But Spain was one of only a few major European countries to remain neutral in the war, and the Spanish media was, therefore, allowed to report on the pandemic.

After the pandemic made headlines in late May 1918, other countries—which were under a media blackout—read about the flu in Spanish newspapers and assumed that it had originated there. (Interestingly, the Spanish called it the “French flu,” because they thought it had spread to Spain from France.)

However, the origin of the 1918 flu strain is still a mystery, though the first recorded cases were identified at a Kansas Army Base.

According to a 2018 MLive report, almost 15,000 Michigan residents died of flu or pneumonia between October 1918 and April 1919; the age group with the highest mortality rate were young adults, ages 20 to 25. Unfortunately, the state did not record flu-related deaths by county. However, the pandemic was so widespread and deadly that its impact can be deduced just from charting overall deaths rates.

Similar to today, the higher death rates were in the more densely populated counties—in 1918, Benzie County had an estimated population of 10,436 (it is close to 18,000 year-round residents today).

- The impact of the virus on total mortality in Benzie was quite small: Benzie had 118 total deaths in 1918, up just 3 percent from 115 deaths in 1917.

- Between January 1918 and April 1919, the county’s monthly death toll ranged from a low of three in March 1919 to a high of 23 in December 2018.

What Makes This Pandemic Different?

A number of structural and cultural changes have impacted the way that countries, states, communities, and individuals are experiencing the second major global pandemic in just over a century.

First and foremost, we live in a connected global world, where knowledge, news, visual evidence, statistics, and—yes—propaganda are served up to us around the clock. The news cycle never ends, sparking fear, wrong conclusions, and both over- and under-reactions of various kinds.

Second, in 1918, we had a robust, war-time manufacturing economy that could withstand the loss of 675,000 American lives more easily than our now heavily service-oriented economy that has furloughed thousands of workers and prompted enormous government spending to support displaced workers and businesses.

Third, medicine and science have progressed dramatically over the past 100 years, and although the loss of life from COVID-19 is devastating, our greater knowledge and understanding is saving lives and will hopefully lead us to more lasting solutions sooner.

Yes, the world population has more than quadrupled since 1918—from less than 2 billion to nearly 8 billion—but the population of Benzie County has not even doubled and is still well under 20,000 citizens. This is one of our greatest assets in combating COVID-19; as of print time, there have only been five cases identified in our county’s citizens, only 11 testing positive at our testing sites (meaning they might reside elsewhere), and no deaths.

What Will Summer Bring?

The short answer to that is, of course, an influx of people—the visitors and summer residents our economy depends on. During the summers, Benzie County’s population more than doubles.

Yet, we also know that more people—traveling from elsewhere—can increase our risk.

Many events, fairs, and festivals have already been cancelled, and public health precautions are being practiced as stores, restaurants, bars, and other establishments slowly open into a new reality. At the same time, many are growing weary of the guidelines that have kept us safe, so far.

But the virus is not tired, says Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Indeed, we continue to see spikes in infections in places where large gatherings of both masked and unmasked citizens congregate, distancing or not distancing.

As we make our way through a summer and fall like no other in memory, let us hope for ongoing awareness of what is at stake and a cooperative approach to keeping our residents and visitors safe. Let this summer season—however different it may be from other years—be one that allows us and our visitors to enjoy all the wonderful attributes of our region, while also practicing respect and compassion for each other.

If you have questions about COVID-19 symptoms, restrictions, or testing sites, visit Michigan.gov/Coronavirus or call the COVID-19 hotline for the State of Michigan at 1-888-535-6136. Additionally, Munson Healthcare has a hotline for COVID-19-related questions—231-935-0951—available seven days a week, from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.

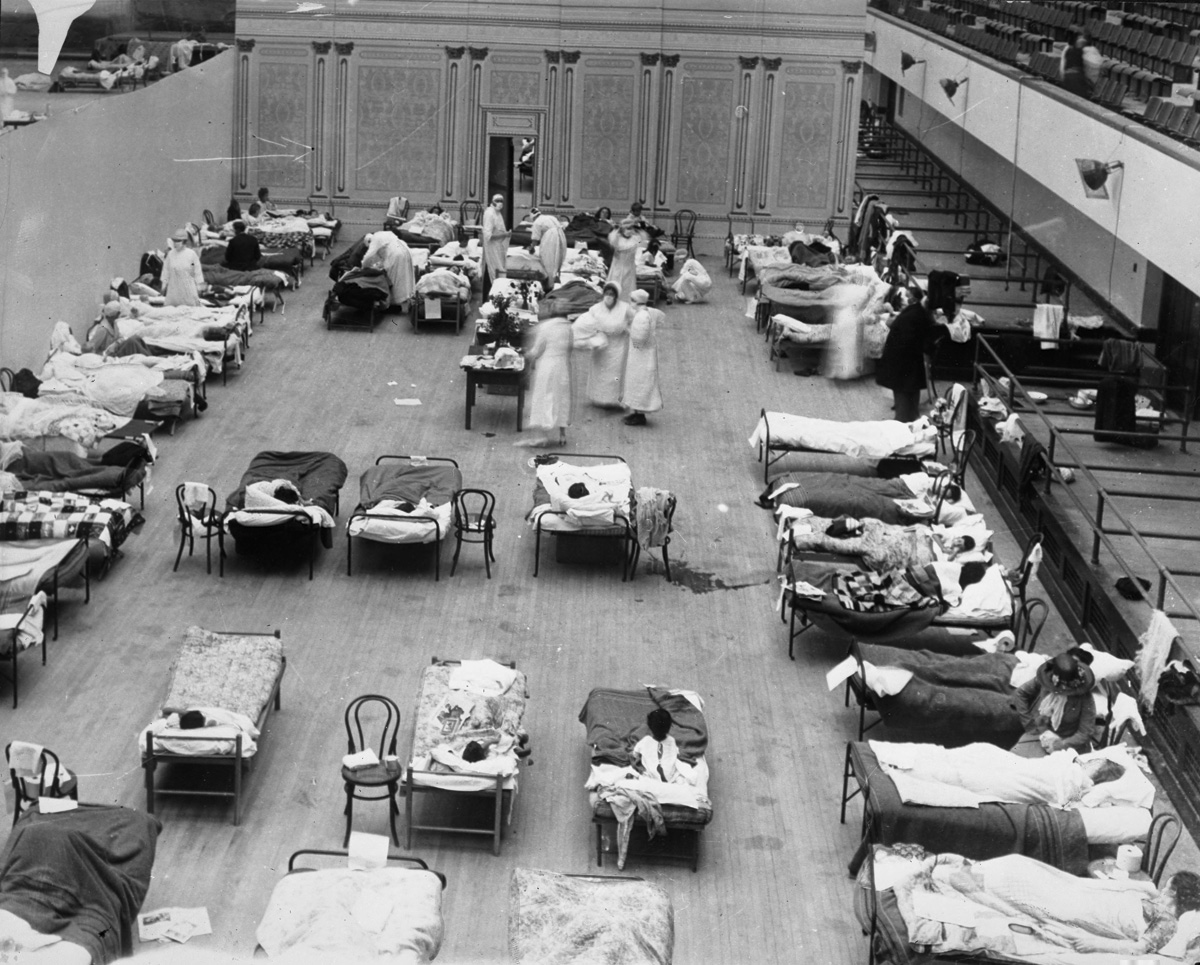

Featured Photo Caption: Volunteer nurses from the American Red Cross tend to patients in the Oakland Municipal Auditorium in California, which was used as a temporary hospital during the 1918 flu pandemic. Photo courtesy of Edward A. “Doc” Rogers (1873-1960), from the Joseph R. Knowland collection at the Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library. Public Domain.

SIDEBAR

Why “Spanish” Flu?

Many people incorrectly assume that the 1918 flu pandemic was dubbed the “Spanish flu,” because it originated there, but that is not the case.

During World War I, the countries that were participating in the war were censoring news of the flu, in order to keep up morale. But Spain was one of only a few major European countries to remain neutral in the war, and the Spanish media was, therefore, allowed to report on the pandemic.

After the pandemic made headlines in late May 1918, other countries—which were under a media blackout—read about the flu in Spanish newspapers and assumed that it had originated there. (Interestingly, the Spanish called it the “French flu,” because they thought it had spread to Spain from France.)

However, the origin of the 1918 flu strain is still a mystery, though the first recorded cases were identified at a Kansas Army Base.