And the city they built

By Jed K. Jaworski

Current Contributor

As Frankfort residents and visitors gaze lakeward, they see distinctive lights at the westward terminals of long ribbons of stone and concrete that extend out from shore.

If you are a mariner, you know breakwaters, piers, and lights well. When looking to escape the life-threatening torrents of a Great Lakes storm, nothing compares to the sense of calm and safety that a mariner experiences when you and your vessel at last find shelter behind their protective arms. On a dark, stormy night or during a fog-bound passage miles offshore, there is the reassurance of the lone lighthouse beacon and fog signal guiding you home and to safety.

To land-lubbers, the piers are a special opportunity to literally walk out onto the inland sea, smell the cool lake air, hear the sounds—even the silence—and gaze landward for a unique perspective of life ashore.

The piers are, however, even much more than that—they are at the very heart of our community’s existence, from its very start.

In what was then an uncharted wilderness, the Aux Becs Scies River (now called the Betsie River) meandered its way to Michigami (now called Lake Michigan). Just before casting itself into the great freshwater sea, the river broadened out into a beautiful marshy wetland, surrounded to the north and south by immense forested hills of beech, hemlock, and maple. Cold, clear artesian spring water joined from both sides of the river as it formed a little lake (now called Betsie Lake or erroneously Betsie Bay) nestled below the hills, with a forested dune dividing it from Lake Michigan.

From Lake Michigan, this little inland lake was virtually concealed from view by the dune, save for the northwest corner, where its waters pushed their way into the Great Lake’s powerful surf. It is here that famed French Jesuit missionary Father Jacques Marquette is said, by some, to have died and been buried in 1675. (Editor’s Note: In June 2020, The Betsie Current published an article about the discrepancy of whether Father Marquette was buried in Frankfort or in Ludington; see our online archives.)

The southwest corner of the little lake harbored a favorite Native American respite, where a spring flowed from a hillside that sheltered the encampment. It would be 1838 before U.S. government surveyor Alvin Burt would map the existence of the serene location and note its qualities. Still, it would take two decades more before big development projects came to Frankfort—though, in addition to the First Peoples, a few white settlers would brave the elements to carve out their homesteads. (See sidebar.)

In 1854, European exploration and settlement was working its way westward on the Great Lakes. Struggling in a late fall storm that year, the schooner Navigator—under the command of Captain James Snow—was bound for Chicago.

Leaking badly and soon to founder with all aboard, in a desperate attempt to save the crew, Captain Snow decided to run the ship into the shore, in hopes that—by some miracle—they might survive before the vessel was broken to pieces by surf on deadly sandbars off the beach. When near the shore, Captain Snow saw the Aux Becs Scies River where it entered Lake Michigan and decided that heading there could mean salvation. Under full sail, he pressed the vessel over the sandbar and right up the river.

To his amazement, there lay a calm, serene, hidden lake of perfect refuge. Lake Aux Becs Scies had now been “discovered” by the people who would, arguably, appreciate it most—Great Lakes mariners in search of a refuge and commerce.

Captain Snow soon put word out about the little lake’s splendid potential for a thriving harbor and town site.

The problem was, however, that only small vessels could navigate the river to and from Lake Michigan—and even then only under certain conditions.

Building a large wooden dock out into Lake Michigan—as some other emerging town sites had done—was a futile undertaking, as fall storms and winter ice quickly destroyed them. Additionally, they offered no protection to mariners utilizing them, and ships were often cast ashore when onshore wind and sea arose.

Eventually, the Frankfort Land Company, an investment group, purchased land along the shores of Lake Aux Becs Scies in 1859; they named their prospective town “Frankfort on the Lake” and funded men with wheelbarrows, shovels, pilings, and planks to build the first piers with a goal of improving access to the harbor. (Editor’s Note: See Andrew Bolander’s historical account of the Frankfort Land Company in our online archives.)

One year later, however, storms destroyed the workings.

Around this time, E.G. Chambers purchased land on the south shore of Lake Aux Becs Scies. Being politically connected and having served in the Lincoln administration, he petitioned the U.S. Government to survey and improve the lake outlet with more substantial piers.

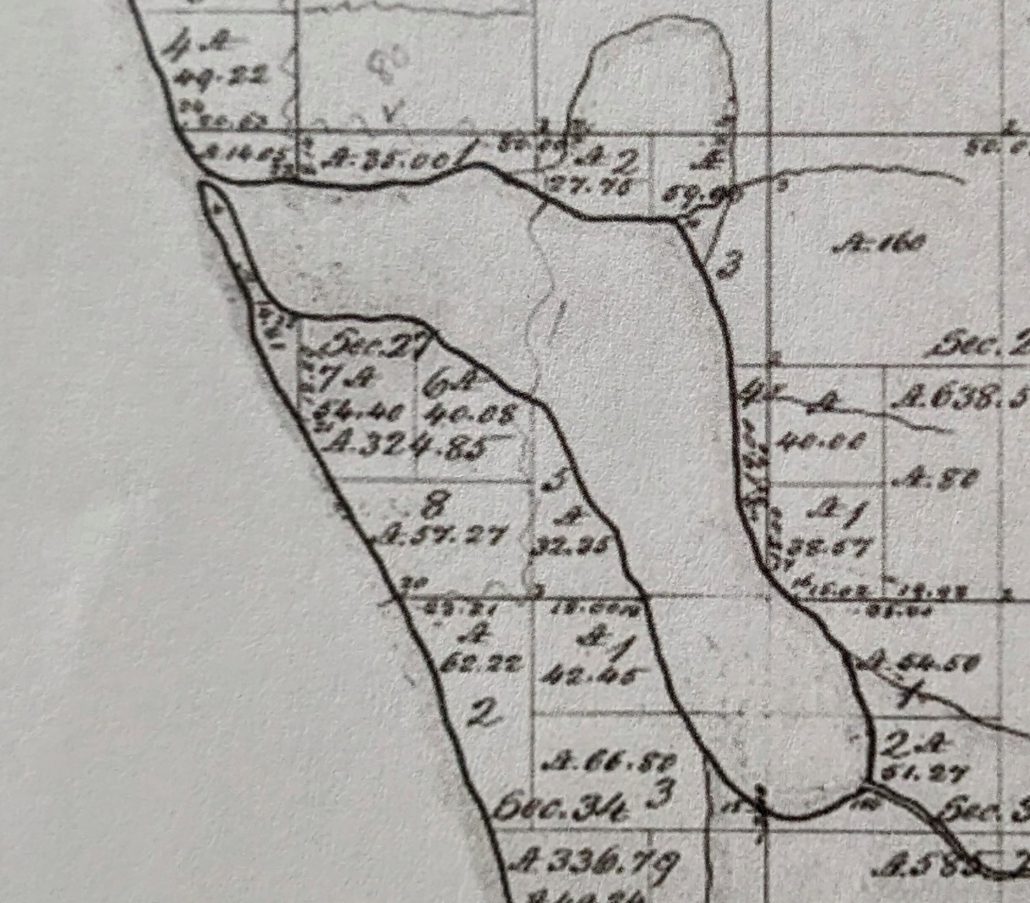

After the Civil War ended, the government agreed and provided funding to develop a plan and to implement it. The plan ambitiously called for the natural river outlet—at what is now Cannon Park, at the foot of Frankfort’s Main Street—to be abandoned. Instead, an entirely new channel was dredged out and piers were constructed on the southwest corner of Lake Aux Becs Scies.

Finally in 1867, the much anticipated day arrived.

While looking through his spyglass, Point Betsie’s Lighthouse Keeper Alonzo J. Slyfield discerned a fleet of vessels and equipment—including an immense steam-powered dredge—working their way toward Frankfort. He quickly whistled for his trusted dog, Hero, attached a note to his collar, and sent him running four miles down the beach to alert the budding town of the much-anticipated arrival.

Everyone from miles around, including very curious Native Americans, marveled at the array of men and fascinating equipment put to the task. In a matter of a few days, the dredge had made an eight-foot-deep channel into Lake Aux Becs Scies and commenced digging the new 200-foot-wide channel on the south side of the lake.

Wooden cribs—20 by 32 feet—sunk 12 feet into the lake bottom and filled with seven cords of Wisconsin limestone would line the channel and extend 800 feet into Lake Michigan. The project proved a great success, and what soon came to be known as “Frankfort Harbor” quickly became a vibrant commercial port.

In 1873, the South Frankfort Iron Works began operations, utilizing the new harbor to import raw materials and export their products.

Also in 1873, the first pier light was established on the south side of the channel, exhibiting a red light atop a white wooden structure. A raised wooden walkway was constructed to allow the Light Keeper to make his way out to tend the light during high seas. Despite this, an unfortunate tragedy occurred in 1881, when the Canadian steamship Columbia foundered off Frankfort at dusk in a storm.

Having drifted in lifeboats for miles in the dark, confusion ensued when the crew tried to discern which side of the pier was the entrance to Frankfort Harbor. Consequently, one lifeboat safely landed, but the other errantly rowed to the outside of the pier and capsized in the surf, killing many of the occupants. (Today, one need only recall the sailors’ rhyme “red, right, returning from sea”—an old adage to remind those returning from seaward to harbor that the red light should always be on their right side—to help ensure safe passage and avoid a fate such as the Columbia’s passengers and crew.)

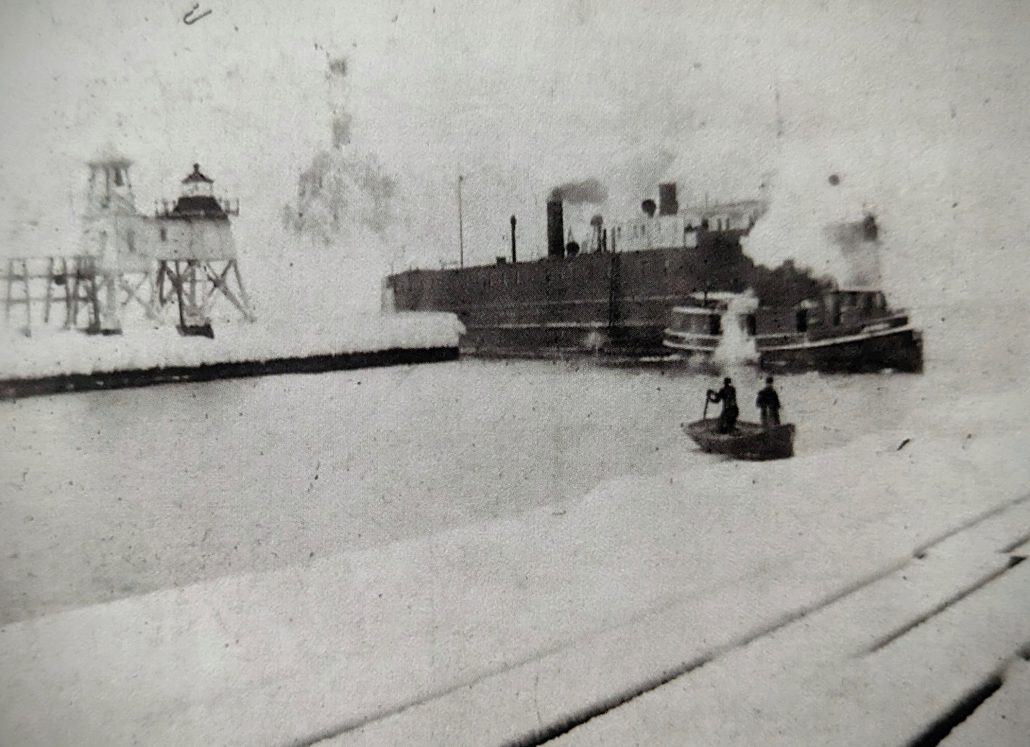

In 1892, a fog bell and wooden support structure were established just behind the light on the south pier—a timely addition, as the world‘s first fleet of open-water rail ferries, via the Ann Arbor Railroad, would call Frankfort Harbor home port later that year.

Ensuing years saw lengthening and other improvements to the piers.

For instance, a persistent problem was no quarters for the Lighthouse Keeper, only a warming shack and oil house. Walking from his rented home in Frankfort, the Keeper had to launch a boat and row to the south pier to tend the light, a laborious and dangerous endeavor. This was born out in tragedy, when in 1902, Assistant Lighthouse Keeper Sheridan King was accidentally crushed to death by the Ann Arbor Ferry #3 while trying to secure the rowboat.

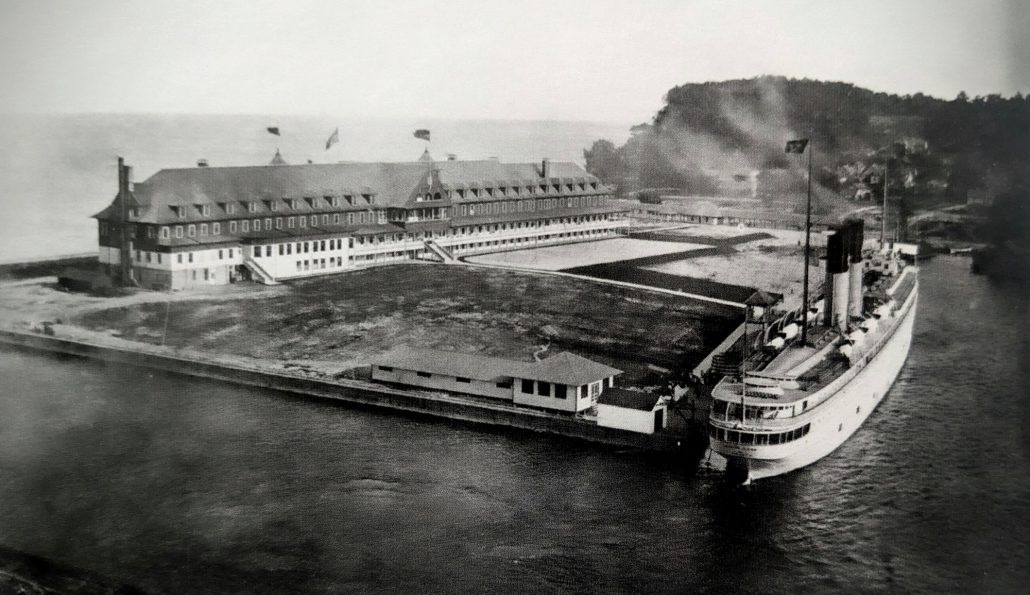

A few months later, the piers would see happier times, though, as more than 1,200 guests attended the grand opening of the large and glamorous Royal Frontenac Hotel, which had been constructed by the Ann Arbor Railroad at the foot of the north pier. (Editor’s Note: The Betsie Current published a historical piece by Jed Jaworski on the Royal Frontenac in February 2021; see our online archives.)

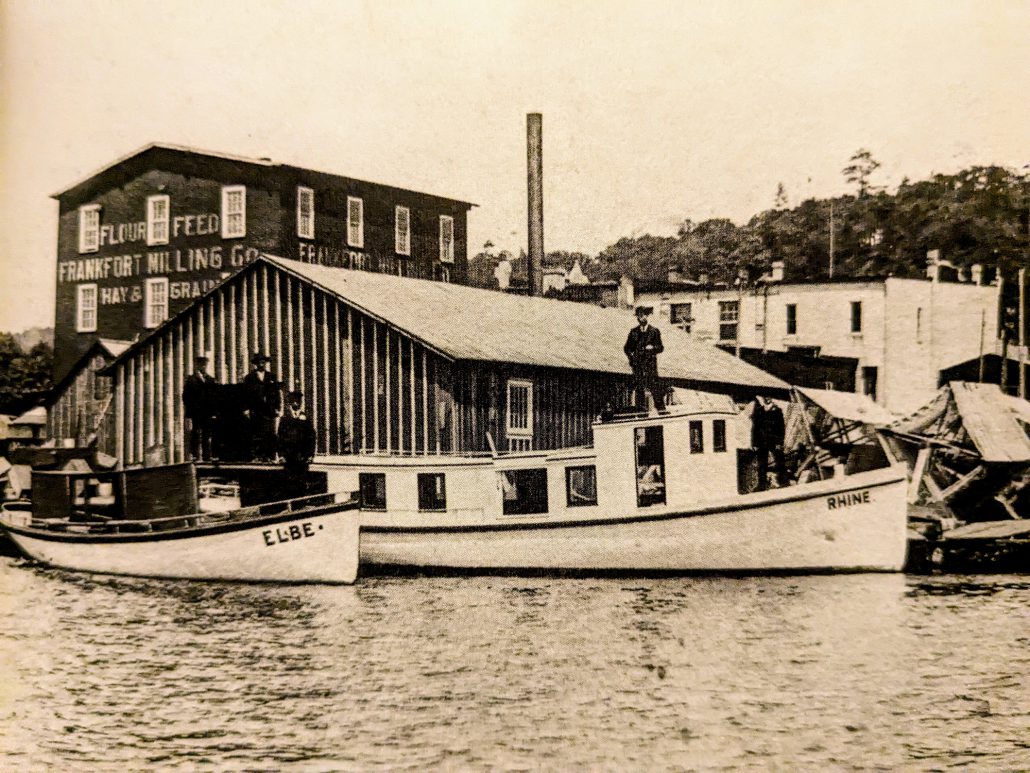

But another tragedy occurred in 1908, two days after Christmas, when the locally owned fish tug Rhine—returning to Frankfort on a stormy night—was driven against the unilluminated north pier by the large seas, killing all aboard.

Moreover, as ships became larger and more frequently entered the harbor in all manner of weather, a perilous problem began to occur.

Sandbars would form across the ends of the piers; in a heavy sea, a ship’s bow could strike bottom and send it careening broadside onto the end of the pier, thereby impaling the ship or putting it aground. In an unusual attempt to rectify the problem without frequent and costly dredging, the Ann Arbor Railroad, operators of the ferry fleet, installed perforated pipes underwater more than 1,000 feet out from the piers. Through these pipes, oil could be pumped to calm the seas—whether the Ann Arbor Railroad was indifferent to, or ignorant of, the impacts to the environment and the beach at its own Royal Frontenac Hotel, it was fortunate that the system soon failed, as the hand of nature quickly plugged the pipes with sand. The oil-pumping operation was abandoned.

A more logical—though costlier—approach to the problem was extending the piers to deeper water.

So in 1912, the piers were extended and the lighting was improved. The old wooden south pier light and bell tower were removed and replaced by a red light on a steel tower. A new structural steel square tower—painted white—was installed at the end of the north pier with a fixed white light, a fog siren, a storm walk, and a range light near shore.

In 1918, the lights were electrified, and the fog siren was improved to a compressed air diaphone. (This created the deep resonant sound that had previously given Point Betsie its distinctive voice, saying “Baaay Rummm.” Many long-time residents can recall the sound of Point Betsie’s and Frankfort’s diaphones talking back and forth to one another on a foggy night.)

The improved light and fog signal equipment played a lifesaving role on a February night in 1923.

The Ann Arbor Ferry #4 had taken a brutal beating at sea; heavily damaged and sinking, they were desperately seeking the refuge of the harbor. Through the blinding snow, the captain was able to discern the sound of the fog signal and hence managed to make it just inside the piers, before sinking adjacent to the south pier. The Coast Guard—lashing men together with life lines—extricated the freezing crew from the sunken ship utilizing the ice-covered pier with no loss of life.

The old wood crib structure of the piers were showing their age by the late 1920s, and after years of planning and financial wrangling, a new and improved pier and arrowhead-shaped breakwater system was designed and funded.

The new system would create a “calming basin” to minimize heavy seas running up the channel and a much wider entrance, free from the dreaded sandbars. The plan also provided for the north and south towers to be heightened and a decommissioned Lighthouse Keeper’s dwelling to be brought up by barge from Chicago and set ashore in Frankfort near a newly planned Coast Guard station (now the Oliver Art Center).

The contract for the south portion was given to the Great Lakes Waterways Company in 1928. (An employee, Elroy “Duke” Luedtke, would have a consequential impact later, when he would establish the Luedtke Marine Engineering Company in Frankfort.)

Using concrete caissons filled with rock and capped with concrete, the Great Lakes Waterways Company created the south breakwater, demolished the old pier, and improved the channel stub pier. The project was completed by 1931, however—due to bad weather, hard luck, and the Great Depression—it would be the contractor’s last job.

An ambitious Duke Luedtke, with his fledgling company, bid on the north breakwater job, but it was awarded to the large Great Lakes Dock and Dredge Company, who were, in the end, able to efficiently complete the work in a miraculous six months.

Just as it did in 1867, the construction spectacle 64 years later brought great crowds to the beach.

Nineteen immense 20-by-54-foot caissons were built in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, taken across the lake, and sunk to help create the 1,972-foot-long north breakwater. More than 3,500 yards of concrete were used, along with 500 22-foot-long round pilings; 905 pieces of 2-by-12-foot piling at 45 feet long; 2,000 pieces of 9-by-12-foot steel sheeting; 75,000 pounds of reinforcing iron; 35,000 bags of cement; 63,000 tons of stone; and 50,000 board-feet of lumber. Additionally, 1,157 feet of old pier were torn out and removed. The north pier light was set atop its new base, raising it from 46 feet to 72 feet tall, making its 17,000-candle-power Fourth Order Fresnel lens, visible 14 miles offshore—more powerful than it has ever been.

The improvements provided great strides in safety and protection for the harbor, but Frankfort-Elberta was still not immune from tragedy.

The fish tug Jean R—when stuck in ice with a heavy sea in February 1935—was carried into the breakwater, where it was stove-in and sank. The crew of four survived by tying themselves together with a life line and crawling along the ice-covered breakwater to safety.

Our piers and lighthouse structures have seen and facilitated the harbor’s transformation from a wilderness hamlet to a bustling commercial resort, as well as an agricultural and industrial port—and now to a non-commercial recreational port.

They have endured fire and ice, the worst of Great Lakes storms. They have seen lives saved, lives lost, and mighty ships founder. They are as much a part of the character and fabric of our town as anything in our community. They also remain an important part of our future.

With the loss of the car ferries in 1982, the Luedtke Engineering Company in 2023, and boatyard services for recreational boaters in 2024—for the first time in over 157 years—there is no longer commercial businesses in the Frankfort/Elberta Harbor, save for the refueling and dockage of pleasure boats, as well as the few remaining charter fishing services.

Unfortunately, the harsh environments in which these harbor structures exist still require expensive maintenance that seasonal pleasure boat traffic may not support—it is unknown whether “harbor of refuge” status will warrant future federal investment in the harbor’s infrastructure, as it has over the last 157 years.

The U.S. Coast Guard has already divested of the lighthouses at Frankfort and Point Betsie, which are now both cared for locally. Please consider supporting local efforts to help keep these revered solitary sentinels of strength, individuality, and purpose a vibrant and continued part of our community. (See below.)

As much as one can muster a reverence for concrete, stone, and piling, the next time you gaze to Lake Michigan’s majestic expanse and setting sun from the foot of Main Street, give a thought to the piers with their white, red, and green lights; to the way they connect lake and shore; and the way they connect our communities to thee past and future.

The City of Frankfort obtained the North Breakwater Light in 2011 under the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act (NHLPA) program. The City is dedicated to the full preservation of this structure, which stands as a symbolic tribute to our maritime heritage. Currently, $132,000 has been raised of the $1.1 million estimate that is needed. Meanwhile, the U.S. Corps of Engineers, which is responsible for the piers, is in the process of designing a new breakwater system for Frankfort Harbor, according to Joshua Mills, city manager.

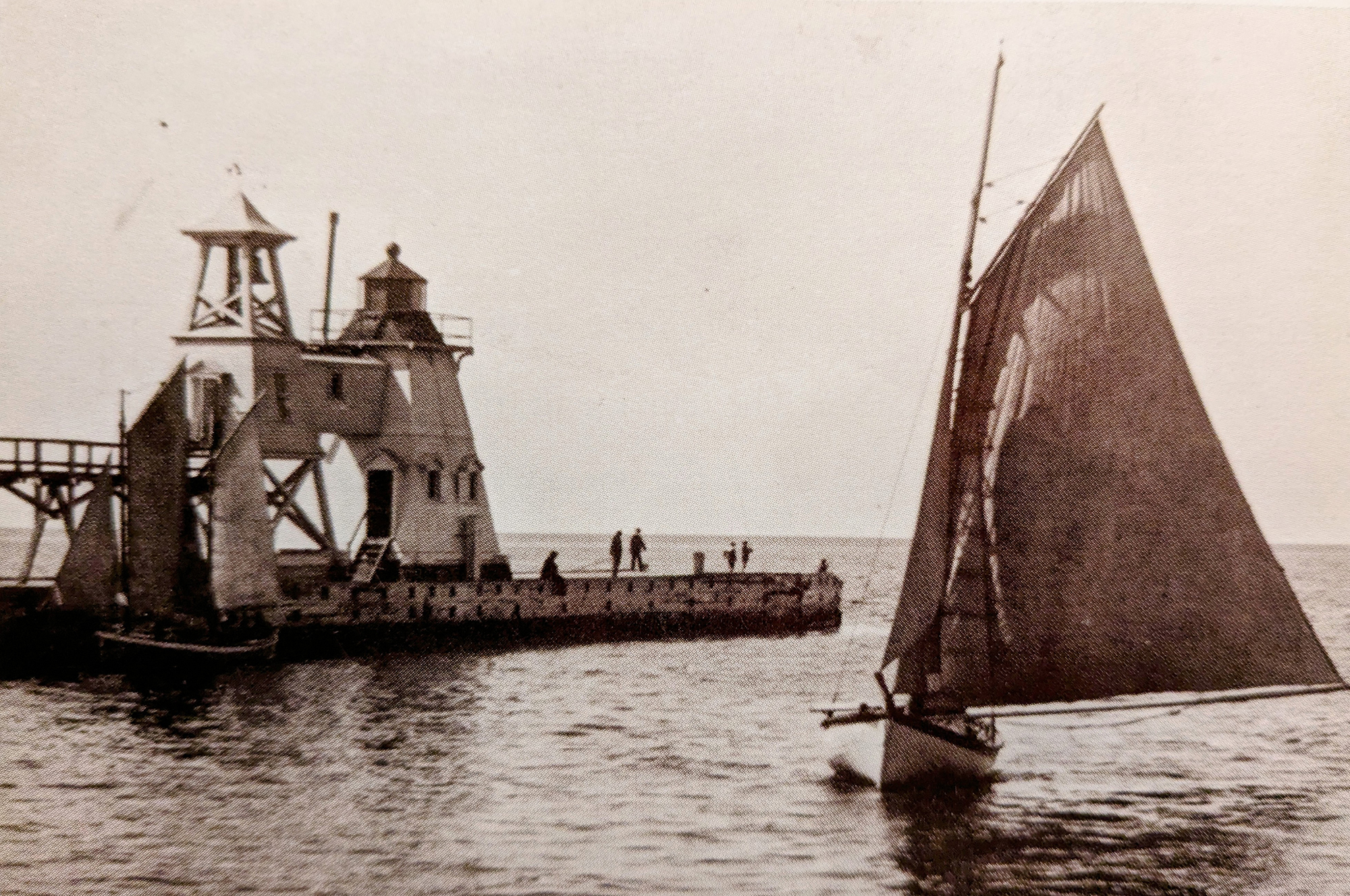

Featured Photo Caption: A gaff-rigged sloop sails into the Frankfort Harbor with the original wooden south pier storm walk, light, and bell towers in the background. Photo courtesy of the Benzie Area Historical Society.